In keeping with the "unpopular opinions" theme of this issue, I want to make a case for nuclear power. Not nuclear power as we normally think of it — vast generating stations (and equally vast price tags) with their domed reactor buildings and shapely cooling towers — but small modular reactors, or SMRs. Comparing SMRs with conventional nuclear stations is almost like equating nuclear power with nuclear weapons, which, however irrational, is often done, as if generating electricity from nuclear fission is on a par with the evils of weaponry.

Currently, 99 large (1,000- to 2,000-megawatt) nuclear reactors in the United States provide about 20 percent of the nation's electricity needs, compared to about 15 percent from renewable energy sources (hydro, solar and wind). Meanwhile, two-thirds of our electricity comes from the burning of greenhouse gas-spewing fossil fuels. Paris Accords or not, none of these numbers is going to change in the short term. And with the future of renewables still a long-term proposition, we're going to have to rely on nuclear power to handle our insatiable demand for electricity — or else live with the ravages of coal and other fossil fuels. In the medium term, nuclear power is our best bet for relatively clean energy.

While no nuclear plant is ever going to be 100 percent problem-free, newer systems are far, far safer than the older Three Mile Island-style designs. The third-generation, 1,100-megawatt Westinghouse AP1000, for instance, incorporates a gravity-fed passive core cooling system, meaning it doesn't rely on external power to cool the reactor in the event of a catastrophic malfunction (the main design failure at Fukushima).

Large nuclear power plants have been and will continue to be financial boondoggles, costing anywhere from $5 billion to $15 billion and taking up to 20 years from initial design to operation. (More than two-thirds of the cost of nuclear power goes into paying back construction costs and associated finance charges, plus funding future decommissioning.) The AP1000, for instance, was supposed to be economically viable, yet Westinghouse declared bankruptcy even before the first plant, in China, was brought on line, and the design is now only kept alive by the resources of Toshiba, its parent company.

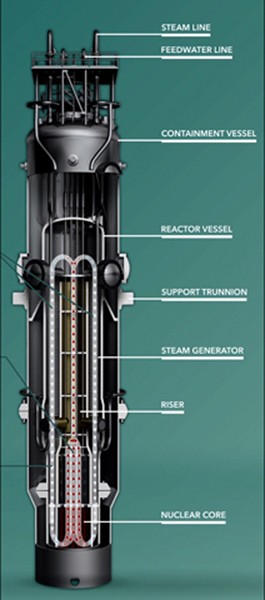

Compared to 1,000-megawatt conventional plants (rule of thumb: one megawatt powers 1,000 households), the output of SMRs is a modest 25-100 megawatts. These modular "nuclear batteries" will be pre-fabricated at a plant, shipped to the site by barge, train or truck, and installed — typically underground in a pool of water — singly or in banks. Currently, the most advanced SMR is NuScale's 65-foot-long, 9-foot-diameter light water reactor (originally designed at Oregon State University). Relying on convection and gravity to circulate water, the module's passive-safe design needs no external power to cool it down in an emergency.

Each NuScale module will generate 45-50 megawatts of electricity, so a bank of 12 could supply the needs of a million-plus population. Building identical units at a central manufacturing facility is inherently safer than in-situ construction of a conventional nuclear power station, while the cost of a single NuScale SMR is estimated at about one-twentieth of that of a 1,000-megawatt plant. Plus, the modular units can be readily swapped out and/or decommissioned.

This optimistic scenario is all in the future, with the first NuScale scheduled to come on line in 2026. My fingers are firmly crossed for the success of this and other SMRs, which have the potential to transform the nuclear electric industry with safe and economical alternatives to huge power stations.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) never believed nuclear power would give us electricity too cheap to meter.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4