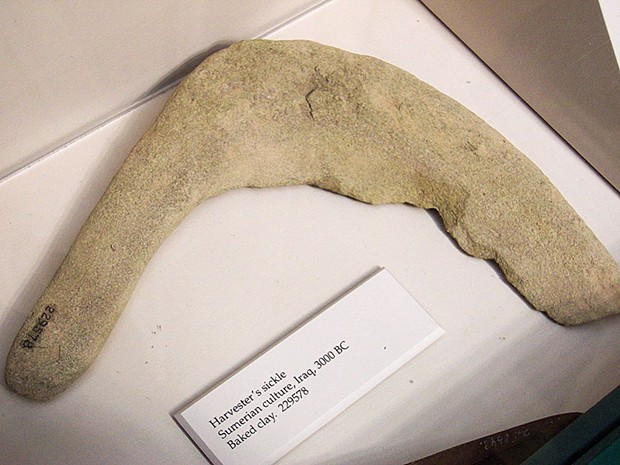

- Photo by Maksim via Creative Commons

- Sumerian baked clay sickle, circa 3000 B.C. Sumerians began farming and domesticating animals 2,000 years earlier. Sickles were used to cut and collect grains like wheat and barley. With a surplus of storable food, the population grew, eventually resulting in urbanization.

The downturn in human nutrition began long before Ray Kroc brought Big Macs to the masses, Coca Cola conned developing countries into buying their addictive sugary concoctions and Nestlé weaseled its way into babies' bellies with formula milk. Long, long before.

Archeologists call it the Neolithic Revolution, the series of events that started in the Middle East's Fertile Crescent about 12,500 years ago, when nomadic hunter-gatherers settled down to become domestic agriculturists and herders. It was a watershed moment, the time when history began. And a bad move, according to anthropologist-author Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs and Steel). "The worst mistake in the history of the human race," he called it in a 1987 essay. "With agriculture came the gross social and sexual inequality, the disease and despotism, that curse our existence."

Building on the work of other "revisionists" (whom he mostly fails to credit — WTF?), Diamond made his case by citing a slew of findings that challenge the "progressive" case, i.e. that agriculture gave us "the Splendors of Civilization." Instead, for Diamond, it was the start of "the Highway to Hell." For instance:

Traditionally, farmers concentrate on growing high-carb cereals: rice, wheat and maize (corn). Even today, we — the global population — get more than half our daily calories from such starchy grains. (In affluent countries like ours, we also eat grain-fed animals.) Hunter-gatherers, on the other hand, have a much more varied and healthier diet of dozens of plants supplemented with animal protein.

According to anthropologist Richard Borshay Lee's work with !Kung San people in the Kalahari (some of the last hunter-gatherers), these bushmen typically spend no more than 20 hours per week obtaining food. For Hadza nomads of Tanzania, it's 14 hours or less. Tell that to your 80-hour-a-week stockbroker stuck in a traffic jam trying to get to work.

Ancient skeletons from Greece and Turkey tell us that the agricultural settlers were weaker and shorter (height being a proxy for health) than their hunter-gatherer forebears. Men's average stature fell from 5 feet 10 inches to 5 feet 6 inches; women's from 5 feet 5 inches to 5 feet 1 inch.

Diamond cites studies of Native American skeletons from the Dickson burial mounds in Illinois as indicating a health change for the worse when hunter-gatherers there settled down some 900 years ago. Life expectancy fell from 26 to 19 years, while "the farmers had a nearly 50 percent increase in enamel defects indicative of malnutrition, a fourfold increase in iron-deficiency anemia, a threefold rise in bone lesions reflecting infectious disease in general." (Skeletons can tell us a lot!)

Parasites and epidemics (bubonic plague, tuberculosis, etc.) can't take hold in scattered, nomadic hunter-gatherer groups. That requires dense populations of people — towns and cities — that develop from sedentary farming societies.

Apart from all the nutritional and health changes wrought by the Neolithic Revolution, the real problem, according to Diamond, was the rise of hierarchy, haves versus have-nots. He writes, "Hunter-gatherers have little or no stored food ... like an orchard or a herd of cows: They live off the wild plants and animals they obtain each day. Therefore, there can be no kings, no class of social parasites who grow fat on food seized from others." Veteran anthropologist Marshall Sahlins puts the issue in a broader context, arguing that that hunter-gatherers took what he calls "the Zen road to affluence": they were affluent not because of how much they had, but how little they needed.

Next week, we'll look at some of the ramifications of Diamond's "catastrophe" thesis.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) is left wondering where hunter-gatherers get their morning cuppa joe.

Comments