During a late-night broadcast in February of 2018, the Humboldt Free Radio Alliance, a long-running independent F.M. radio station, played an audio recording from the Kurdish People's Protection Units, the Kurdish military forces commonly known as Y.P.G.

"My name is Paolo Todd," came a man's voice, calm and clear. "I'm from California. My Kurdish name is Kawa Ahmed. I came to Rojava to support Kurdish people and indigenous rights around the world. We are going to the front lines. I'll be in a heavy weapons unit. I'm very happy to do this to support the Kurdish People, to support the Rojava revolution. Long live Kurdistan."

The radio show continued with a few more recordings from the Northern Syrian autonomous zone of Rojava: music from the region, explanations of the budding Kurdish experimental democracy and homages to people who had fallen in the fighting there. Then D.J. Dhinn got on the air and somberly said he had just received a text message from a listener.

He read it aloud: "I was a housemate with Paolo Todd, here, in Arcata. He died in Kurdistan. Thanks for playing this. Long live Rojava."

Suddenly, the global became local.

As part of Operation Wrath of Euphrates, one on the largest U.S. and NATO-led military campaigns against the mass-murdering, fundamentalist Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Paolo Todd — a man who'd spent years doing community organizing work on the North Coast — was killed Jan. 15, 2017, serving in the Kurdish YPG Militia. He was 33.

Almost two years later, Todd's sacrifice — and the decisions that led to it — take on new resonance, offering a uniquely local lens through which to see global events.

As this issue of the Journal went to press, the BBC was reporting that the Turkish military was dropping phosphorus, a chemical weapon, on civilian Kurdish populations in Northern Syria. As a direct result of President Donald Trump pulling remaining U.S. forces from the region, Turkey immediately launched operation "Peace Spring," in which it proclaimed a "Safe Zone" that "must be cleared" of any Kurdish people. According to Kurdish officials in Syria, the Turkish occupation has displaced more than 400,000 people, including 18,000 children, and resulted in the deaths of more than 500 civilians.

Kurdish politicians and journalists have been rounded up, beaten and extra-judiciously executed, while the absence of U.S. and Kurdish forces at prisons holding thousands of ISIS members has allowed them to escape and re-join the fighting, resuming the slaughters that had been stopped largely through Kurdish efforts.

In response to Turkey's annexation through military force, Trump spoke from the Roosevelt Room of the White House.

"It was a lot of, a lot of pain for a couple of days and sometimes you have to go through some pain before you can get a good solution," he said. "But the Kurds are very happy about it ... We've taken control of the oil in the Middle East, the oil that we're talking about, the oil that everybody was worried about. We have — the U.S. has — control of that."

Contrary to Trump's claims, reports from the ground in Northern Syria indicate the U.S. withdrawal and subsequent Turkish occupation of the area has been devastating to the Kurds and Rojava, the people and the cause Todd gave his life to uplift.

How did Todd, a California Native, come to decide he'd leave his life of community organizing on the North Coast to travel to the Middle East to take up arms with people he'd never met in a remote part of the world like Kurdistan? The answer is that no one really knows. Todd seems to have kept his plans secret, telling people in November of 2016 that he was travelling to Turkey to teach English. But hours of interviews with friends, family and co-workers offer some insight into why Todd may have traveled thousands of miles to join a violent conflict.

Born in 1983, Todd was raised in Pasadena and attended the University of Oregon from 2001 through 2005, graduating with a religious studies degree. After college, he took classes in teaching English as a second language and lived in China for two years, where he taught English and became fluent in Mandarin. After returning to the states, Todd applied for a job in Humboldt County at the suggestion of one of his closest college friends, Klamath resident Thomas Wortman.

"I met Paolo in college," Wortman said. "He was my roommate in the dorms for the Native American Summer Bridge program ... He moved to Klamath seven or so years after college and lived and worked on the Yurok reservation for almost two years. Then Paolo moved to Arcata to work for other nonprofits and go for this liberal, West Coast, small-town experience."

In certain ways, the history of the Kurdish people is similar to that of Native people in the United States and some believe the same forces that drew Todd to the reservation in Klamath also pulled him to the Middle East.

After World War I, Middle Eastern land was divided with nation states created from areas that had previously been occupied by a mix of Muslim caliphates and migratory tribal peoples, creating what are now the countries of Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey. In this process, the Kurdish people, whose historic range included parts of all those countries, were not given a nation state of their own. This is not so different from when the U.S. went to war with the French and the Spanish to claim the land and resources of the indigenous populations here in North America and then created states without regard for the pre-existing boundaries recognized by the Native populations living within them.

A video of Todd posted online, the audio of which was used in that Humboldt Free Radio Alliance broadcast and was created by the YPG to garner support for its cause among Western audiences, shows him smiling and speaking proudly with an AK-47 slung around his neck. He's wearing a distinctive Yurok patterned knit cap.

"Paolo was part Native American but not Yurok, but he worked for a couple of years on the Yurok reservation," Todd's father, Dave Todd, said. "He was working technically for the Humboldt Area Foundation, doing community organizing both on the reservation and among working class white people in the Klamath area ... typical community organizing, to help people, you know, stand up for their rights in general, get better educational opportunities and bring other resources into the community. He was pretty active in politics up there; he also worked on Measure R ... to raise the minimum wage to ($12). I think we still have one of his signs for that."

Josh Norris said he worked closely with Todd during the fledgling days of the nonprofit that would become True North Organizing Network.

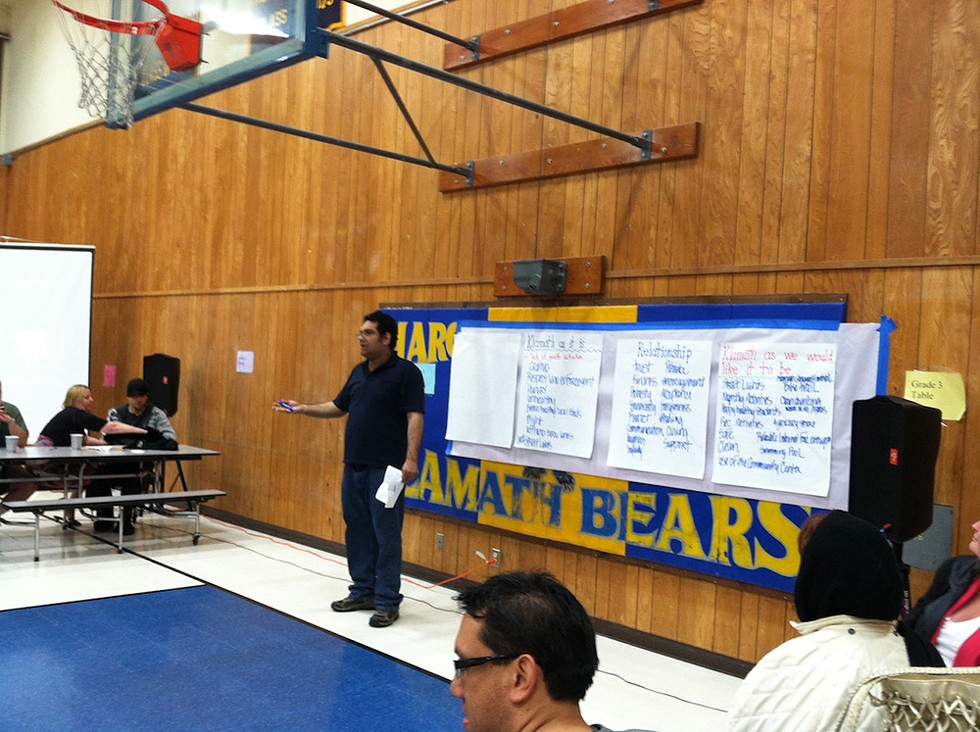

- Photo by Claire Reynolds

- Paolo Todd with attendees of a Klmath Organizing Committee meeting at Margaret Keating Elementary School

"It was a project of Building Healthy Communities through which we had local organizing committees," Norris said. "The one here in Klamath was called the Klamath Local Organizing Committee. It was a collection of community members drawn together by common values, and those values determine some of the changes they want to see. They would do research to figure out what could be changed, and they would figure out maybe who the policy makers are, those in power, then do some sort of action to bring about policy change. That's in a nutshell what the organizing was. Direct democracy was the idea and Paolo was all about that.

"We actually picked up one of his issues after he left, I believe even after he passed," Norris continued. "We had an action ... to bring more recreational opportunities to Klamath youth. We got the Del Norte County Parks and Rec, Resighini Rancheria, Yurok Tribe and Yurok Housing Department to agree to work together, to pool their resources, and built a couple of baseball fields, community parks and that sort of thing. Paolo knew a lot of people in the community; he had good relationships with them. A lot of the work is about building relationships with people and putting people in relationships with each other. He was pretty talented at that."

- Photo by Claire Reynolds

- Speaking at the Klmath Organizing Committee meeting.

Rojava is a radical non-state, socio-political experiment that currently involves roughly 2 million people. While predominately made up of Kurds, the "non-state" autonomous region is also ethnically comprised of Syrian, Iranian, Yazzidi, Arab, Aramean, Turkmen, Armenian and Chechen peoples. Rojava follows a form of democratic confederalism set forth by its leader, Abdullah Ocalan, who has been imprisoned in solitary confinement for the last 20 years on the remote island of Imrali by the Turkish government. Through the democratic concepts set forth in Ocalan's writing, local villages and cities are given control of their own decision-making processes. Notably, the political systems of Rojava mandate that representatives on these local councils are of different ethnicities and include women.

Kevin McKiernan, an author, journalist and filmmaker who spent years living in and reporting on Kurdistan, said the notion that this radically progressive form of government has gained a foothold in the Middle East, surrounded by some of the most oppressive regimes in the world, has caught the attention of people around the world.

"One of the reasons that Turkey is targeting Rojava is because of the system that Rojava represents, which is the antithesis of the one that exists in Turkey right now," McKiernan said. "And so they don't like the feminism, they don't like the equality, they don't like the pushback against the excesses of capitalism. They are on the other side of that issue, and they are hoping that they can stamp that out. But it's an idea that is bigger than they are and the Kurds have been betrayed before by people much bigger than (Turkish President Recep Tayyip) Erdogan. The Kurds have seen this movie before."

Given Todd's apparent love for direct democratic processes, one can imagine why he may have been to drawn to Rojava, whose constitution's preamble states, "We, the people of the autonomous regions, unite in the spirit of reconciliation, pluralism and democratic participation so that all may express themselves freely in public life. In building a society free from authoritarianism, militarism, centralism and the intervention of religious authority in public affairs."

Todd certainly subscribed to progressive philosophies and family and friends referred to him as a studied intellectual well-versed in the writings of Noam Chomsky and Murray Bookchin, yet he was playful enough to have dressed up as Zapatista Subcomandante Marcos for Halloween while in college.

While there are various groups across the globe fighting for indigenous rights and autonomy, Wortman, who met Todd in Oregon, said he understands why Rojava particularly may have appealed to his college friend.

"Historically, a lot of these indigenous causes were tied into Marxism, but in this way that they just turned into drug runners, in Columbia or wherever else, because they have to fund the cause. It seems like the Kurds have a pure vision in Rojava of ecology and feminism and collectivism," Wortman said. "To come into a place like Rojava, as big as it was, fighting for indigenous people, it just ticked all the boxes of fighting fascism, achievable goals of liberating this specific town, it was all there, all the things that you would need in order to say that this is a worthy cause ... Like I said, the values are there. Paolo wouldn't have to compromise anything."

It's clear the friendships Todd made in college continued to be very important to him until he departed for Rojava. In an age when texting and social media are the main means of communication for many, Todd and his friends maintained contact through regular, often lengthy phone calls that went into the wee hours of the morning. For Wortman, it was a custom that began in college.

"In the first term, must have been late fall, we were just smoking on the porch of the dorms and stayed up 'till the sun came out, just chatting," he said. "We weren't even drinking, so that kind of started and just kept going after college. We would have these phone conversations that would last maybe six hours. It was like, 'Let's talk tonight, call at 8 and talk until 2 or 3 in the morning. This started in college and continued until he left. Every two months or so, we'd talk like four hours or more and just go over everything we were thinking of at the time. It was like this cool catharsis every time we talked, which made it so strange that we didn't talk about this. I don't know what I would have said if he told me his plans. I don't think I would have tried to stop him but I don't know. We didn't get that chance."

Another of Paolo's college friends, Joel Sokoloff, said he and Todd spoke by phone an average of four or five hours a week for 10 years.

"Paolo was a very private person — to an extreme," Sokoloff said. "I didn't sense he was hiding things, perhaps until the end. He just wanted to give voice to others. I think he always wanted to leave enough breath in his time with people to allow for that. ... He was very empathetic, didn't like to talk about himself that much. Paolo was such a smart person. Some people are satisfied with a simple lot in life but he required a lot more intellectual stimulation and he was never a money person. But I think he craved success in a more pure form of success; accomplishing goals with meaning, and he wasn't (doing that). Looking back, I can see more how he made his way to Rojava.

"It's taken a long time to see," Sokoloff continued, "but it was a higher calling, one that fit his unique view of the world."

Looking over the Pacific Ocean while being interviewed in Crescent City, Wortman wiped back tears as he remembered his friend and the void he left.

"So we were having this 15-year conversation, that's what's so sad to me," Wortman said. "There's just things I don't talk to anyone else about. I've never lost anyone like that before. That's part of my personality. There's just no outlet for it. One thing about him, and this is very cool, Paolo didn't seem to have the same material desires that other people have. He didn't want anything. He didn't want a nice car. He didn't want things or money or a career. It was so strange — he was interested in exploring ideas and tripping out on what fascinated him. A very selfless person."

Todd's brother Rick Todd remains largely frustrated by his brother's death.

"I think it was a waste, to be honest," he said. "It's understandable that the Kurds need assistance and they're probably right in who they are fighting but, at the same time, it's their own fight. I don't think we should have been involved."

Yet, there's part of Rick Todd that understands, too.

"I'm guessing that Paolo saw within the Kurdish people in Syria maybe something that was beginning ... a start of something that was a change and I think if you read about it, they're really big on women's liberation, and I lived in the Middle East myself about 10 years ago and, in many ways, it's a misogynist part of the world. And so for something like this, where you have equal rights between men and women ... it's pretty phenomenal."

There are three philosophical pillars upon which Rojava's system of governance is based, as stated in Article 2 of the Social Contract of the Democratic Confederation of Northern Syria: ecology, democracy and feminism. The last plays a very large part in the political and everyday lives of the Kurds, as it is required by law that women be included in all branches of government and policy-making processes. In some ways, Rojava can be seen as a direct refutation of fundamentalist Sharia law and has made illegal all violence and discrimination against women, including forced marriage, child marriage and honor killings.

Claire Reynolds, who worked with Todd at the Humboldt Area Foundation, said she can see how Rojava's views on women appealed to him.

"With Paolo, I never felt like we were more than colleagues — I didn't feel like there was that odd dynamic between men and women that's either sexism or sexual tension, you know. Neither of those things were happening," she said. "He was just a solid, safe person that gender was really never an issue with. Even though he was a really big, tall guy, I never felt like gender effected how we interacted with each other ... and that's not always the case with people. It doesn't surprise me that he would have that kind of respect and have those goals for women to be treated equally and safely. That doesn't surprise me at all."

In Rojava, there is an all-female sector of the military known as the YPJ (the Women's Protective Forces). It has 30,000 members who are fully trained and help defend the region. These female forces were often on the front lines in battles against ISIS, which reportedly had a demoralizing effect on the enemy, as the fundamentalist ISIS forces — who were known to rape captured Kurdish women and mutilate their genitals — believed that to be killed by a woman in battle would nullify a soldier's promised reward of 99 vestal virgins in the afterlife.

While hard data about the number of foreigners who have traveled to Rojava to take up arms against ISIS is hard to find because they rarely inform their home countries, it's clear Todd was not alone in his decision to go to Kurdistan. Estimates indicate hundreds of foreigners have joined the Rojavan cause, with handfuls killed in the fighting every year.

McKiernan, the author, said there's clearly something about Rojava that resonates globally.

"Struggles aren't confined to ZIP codes," he said. "They spill across borders everywhere and people that want a better world, that are struggling for humanity, they often see similarities with other struggles and they want those to succeed as well."

Wortman said that while he believes Todd went to Rojava to fight for a cause, there was more to it.

"He also just hated ISIS with a real passion," Wortman said. "He would go on these rants, it would be like, 'OK, dude. It's been an hour now. Yes, they're bad.' But he really, really, hated them."

Rick Todd agreed.

"I think maybe my brother wanted to be part of (the Rojava revolution) and he also had a dislike of fundamentalism — religious fundamentalism," Rick Todd said. "He was drawn there for a lot of the same reasons that other Americans go there. I think that the westerners that go there to fight are going there either because they want to fight ISIS, or they are going there because they like to be involved in wars. And my brother definitely wasn't a mercenary. He had no military experience. He went there to fight for the cause."

In the months before leaving for the Middle East, Todd lived with his parents in Southern California to save up money for his trip. In retrospect, Todd's family sees there were signals that Paolo had something in mind. They say he took to working out and losing weight, possibly preparing his body for the excursion ahead. But he never let on to anyone interviewed that he had any intentions of going to war in a foreign militia.

"He called me just three days before he left," recalled Sokoloff. "He said, 'I'm going to teach English,' and he made me guess where ... I went through all these many countries — we talked so many times about the different places he and I would like to travel to — but I was trying to guess all the places that he was going to go teach ... and he's like, 'No, Turkey.' Turkey? Which was strange because he never really talked about wanting to go there, an unofficially Muslim country and Paolo liked to party ... so I was surprised but he sold me on it. I had no reason to doubt him."

Wortman's experience was similar.

"He told us that he was going to Turkey to work at a nonprofit that had something to do with water and it was vary vague and that he was leaving in three days," he said. "I didn't know about the YPG. I didn't know about Rojava. ... So then when we didn't hear from him, I thought, 'I guess he could be doing some sort of humanitarian aid thing there.'"

After Todd left the states, friends and family say his communication was very spotty, with just a few emails.

"And then Trump won the election," Wortman recalls, "and he sends us this really freaky email and he copy and pasted Joel. He sent us both the same weird email that was like, 'All hail President Trump! Things are going really good. Happy to be here. Your friend Paolo.' It didn't sound like Paolo's writing at all and that was the first time that we were like, 'Oh shit! What happened to Paolo? Like, he's in Turkey ... did he get kidnapped?' It was in that email, he wrote, 'Going to a real rural part of the country, won't have internet. Probably won't be able to talk for a while.'"

That was the last communication any of those interviewed received.

As is often the case in the chaos of war, the exact details of Todd's death are not clear to anyone stateside. But according to family, he was killed when an improvised explosive device detonated, with four or five Kurds also killed in the explosion. Five days after the incident, Todd's parents were notified by both the U.S. State Department and Rojava representitives in Washington, D.C.

"The phone rang late at night but we ignored it because no one we know calls that late," Dave Todd recalled in an email to the Journal. "In the morning, we saw that there was a message and it said something about Washington, D.C., and a phone number. We called back and a female voice with an accent said, 'Did you know your son was in Northern Syria?' I said, 'No, we thought he was teaching English in Turkey.' She said, 'There was an explosion.' It took another 10 weeks before his body was returned home."

In Rojava, Todd received full military honors in a ceremony that saw hundreds of people follow his coffin as it was carried through the streets. Comdr. Egid Melahir of the International Revolutionary People's Guerrilla Forces, delivered the following eulogy using Todd's Kurdish name, Kawa Ahmed:

"Today we honor and pay tribute to a true revolutionary hero.

Heval Kawa was an internationalist revolutionary; a fighter in defense of a people who he didn't see as other, but as his own. He loved the Kurds and he loved Kurdistan. While I did not know Heval Kawa personally, I do know that he was full of love and compassion, with a desire to change the world and to fight for freedom.

From the plains of North Dakota, Heval Kawa fought alongside his tribal family at Standing Rock against the barbarism of capitalism and the continued oppression and genocide of the Native Americans by U.S. imperialism.

From Dakota, Heval Kawa traveled thousands of miles from the United States to Rojava to defend and ultimately give his life for a people also fighting for their freedom. Heval Kawa heroically fought against the tyranny and barbarity of Daesh alongside the YPG. In the prime of his life and on his first trip to Rojava, Heval Kawa became a Şehîd, a martyr for the revolution in Rojava. To be a martyr is immortality, for his blood will continue to nurture the struggle and show the path that others will follow.

From the Dakotas to Rojava, all indigenous people's will be free; united against their continued oppression and domination. The future is bright, for justice will prevail. The light will shine through the darkness as millions win their freedom and their right to live the way they want, on their own terms.

Şehîd Kawa, may the great spirit along with your ancestors guide you along your next journey. We give thanks and praise for all you have done. You were and always will be a free Kurd in our eyes. You are one of us and we are blessed to have known and fought alongside you.

May Şehîd Kawa's memory be eternal and may his life continue to guide and inspire the future hevals who will take his weapon and continue the struggle against all oppression and tyranny."

It should be noted that the only reference to Todd being at Standing Rock for the large protests and demonstrations against the Dakota Access Pipeline that the Journal found in reporting this story was from this eulogy, but family members also said that in the months before he departed for Kurdistan, Todd was being rather secretive about his activities.

- A screenshot from a YPG video of Paolo Todd's memorial service shows Kurdish soldiers carrying his casket through the streets of Rojava.

"I think Paolo really saw himself as being part of this really long American left wing tradition of going out to help other people, like the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War," Dave Todd said, referencing the period when more than 3,000 Americans voluntarily went and took up arms in that struggle. "I think he really saw himself that way. We always knew that he was an internationalist and he really didn't care too much about material possessions. I mean, he came from a comfortable home. We're middle class here and he had the benefits of a good education, but I think as he got older he identified more and more with the Native American and minority part of his heritage and became more and more passionate about helping people that needed help ... I think that was a big part of his life and a big part of what he did and how he lived."

Johnny Webb, who shared a home with Todd while the two lived in Arcata, agreed.

"It wasn't completely shocking that he went out there," Webb said. "It was more really impressive, to me, because he had put his money where his mouth was, more so than what most people do ... We would sit around talking about stuff like this and he actually, like, went for it. I was super bummed out at first. I thought, like, 'Oh shit, he was volunteering, huddling orphans or something and a car bomb blew up,' and I thought, 'Oh, man, that's so sad.' But when I found out what he was actually doing ... that's bad ass. At least he went out like that."

Dave Todd tried to explain the Kurdish cultural perspective regarding those who have fallen in defense of Rojava.

"Sehid means martyr in Kurdish and you'll see sometimes that they will refer to Paolo as Sehid Kawa Ahmed," he said. "Their big moto over there is Sehid Namarin, which means 'martyrs never die.'"

Sokoloff, meanwhile, said he still wrestles to make sense of it all.

"I've struggled with any justification he made to go to Rojava," he said. "I can see both sides of the coin. But I wish he were here. There are so many experiences I'd like to have with him, things in my life I'd like to share with Paolo that can never be — to continue that seemingly endless conversation of life. But he lived his will. There were a lot of people back in college who talked a big game about doing radical things, but Paolo is someone who walked his talk, made the ultimate sacrifice."

Ishan Vernallis lives and learns in Northern Humboldt County, working on various interdisciplinary projects. He prefers he/him pronouns.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3