Imagine a stream. Cool, clear water dances over rocks smoothed by time. Pond skaters skim the sunlight-flecked surface. Dragonflies flit between clumps of grass. Birds chirp in the trees overhead. And under the water, tiny endangered salmon -- coho, Chinook, steelhead -- dart among the shadows.

Now imagine that same stream dammed, poisoned with chemical fertilizers, drained by irrigation pipes. The trees slashed and the soil eroded. Garbage and debris strewn about. The bugs, the birds and, yes, the fish -- all gone.

It happens — far too often according to those who monitor Humboldt's rivers and tributaries -- and it's part of a larger problem that might be sucking our already parched waterways dry.

In June, state Fish and Game wardens discovered multiple grows outfitted with illegal water diversions on the Trinity River, featuring hundreds of feet of black PVC snaking through wooden boxes and diesel pumps, and concrete dams blocking tributaries and throwing off the water's delicate Ph balance. The department plans to file charges on dozens of violations from that one sweep alone -- and the season is just beginning. In the coming months, the driest and most critical for the county's watersheds, the grows and diversions will only intensify.

But try to quantify exactly how much secret damage is being done to streams big and small, and it quickly becomes apparent that the details are cloudier than a sediment-choked pool. No government agency has devoted serious time or resources to track illicit diversions. No one is certain whether the problem is getting worse. And no one is sure what the hell can be done to fight back.

[][][]

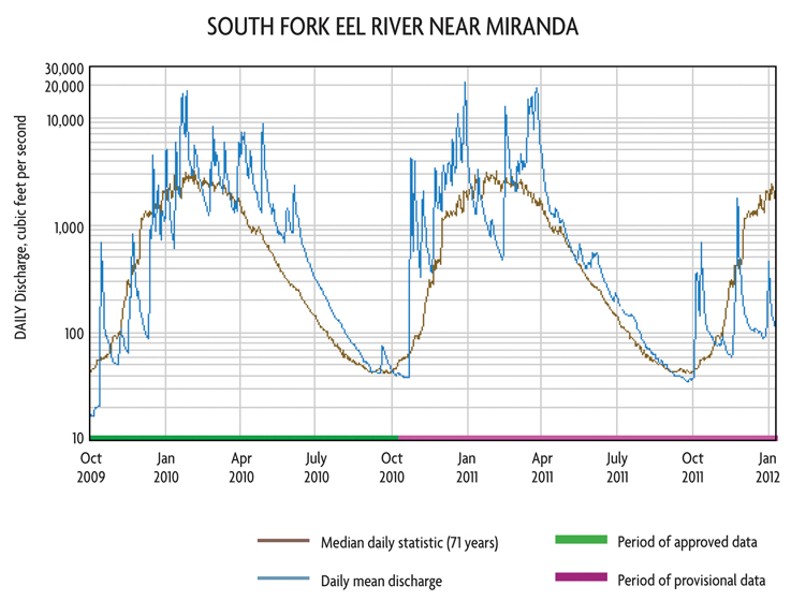

The last two years were wet ones for Humboldt County, according to U.S. Geological Survey data. At one gage in Miranda, flows in the Eel River soared to roughly double the historical average in late 2009, but fell below average by the following October. A winter deluge of nearly 20,000 cubic feet per second became a fall trickle of less than 100 cfs, and a similar pattern played out in 2010-11. The rains came. Then the water disappeared.

Some of it is going to illegal diversions, and specifically to marijuana grows. That we know. How much? That's where things get murky.

"Unfortunately at this point, the evidence is largely anecdotal," says Friends of the Eel River Executive Director Scott Greacen. "Nobody seems to have the kind of overarching data that would allow us to evaluate even for one stream system -- let alone entire watersheds on the scale of the 3,700-square-mile Eel -- what the impacts of illegal diversions are. [But] we know there are a lot of them."

Not every illegal diversion is feeding a pot patch. Some water legal crops or spin a small turbine for household power. However, Greacen says, "diversions for small domestic use or non-consumptive hydropower diversions could be made legal relatively easily with pretty straightforward compliance. The issue remains that most people don't want to let the system know who they are or where they are because their source of income exposes them to law enforcement pressure."

And the pressure on rivers seems to be growing. "Cumulatively we're seeing diversions impact low-flow season more and more every year," says Jane Arnold, staff environmental scientist with Fish and Game. "I can't say who's diverting what, where and when, but what we're seeing on the gages and hearing anecdotally is that there's less water in these wet years than we'd anticipate."

Even District Attorney Paul Gallegos, whose office has begun targeting growers for environmental violations including illegal diversions, has no way to quantify the problem. "The best we can do is speculate," he says. "It's unsupported by numbers."

[][[][]

Why is data so hard to come by? "Monitoring stream flows is an expensive process," explains Josh Smith, who keeps tabs on the South Fork of the Trinity River with the Watershed Research and Training Center in Hayfork. "We don't have funding sources to keep stream gages open. On the whole South Fork watershed, which is about 1,000 square miles, there's one gage."

In addition to thin resources, there's the issue of safety. Like many of his colleagues countywide, Smith frequently treks out winding dirt roads and into thick, uncharted forests. Alone. "Most of the stuff I've found I've found accidentally, and then I get out of there," he says. "I have friends in law enforcement and they say it's not worth it to stick around. It affects how I work and where our crews can go."

While it may be impossible to draw firm big-picture conclusions, Smith is convinced illegal diversions are diminishing water quality -- and killing fish and other aquatic life.

All of Humboldt's waterways face a litany of perils: rising temperatures, sedimentation, pollutants, algae blooms and, in some cases, major legal diversions for hydroelectric power and industrial agriculture to the south. In fact, each of the county's four major rivers -- the Klamath, the Trinity, the Mad and the Eel -- and many of its tributaries are on the EPA's list of "impaired waters," meaning they are too warm, too dirty or too dewatered to meet state water quality standards. Restoration efforts have pulled some rivers back from the brink, but none is robust enough to withstand continued impacts and the looming threat of drought.

Drawing water, even a little, out of streams raises overall water temperature, Smith explains. And a rise of a few degrees can be the difference between life and death for salmon, trout or other members of the salmonid family.

Further, Smith says, most of the diversions he's seen don't use proper screening techniques. "They're sucking up a lot of the juvenile fish and taking them up into the hills to their grows," he says. Out of the frying pan, into the pump.

Smith has been on the job for almost seven years. In that time he's noticed a marked increase in the size and scope of diversions. "There have been people growing marijuana in the woods here for decades. It's really obvious the newcomers have a different system -- we've seen clear-cutting and terrace-building to make these large-scale aggregate grows," he says "Those are the ones that affect water quality in a lot of ways, including the amount of water they're taking."

Greacen draws a similar distinction. "There are a lot of different kinds of diversions," he says. "Some are terrible -- people who block entire headwaters streams. Others are people who pump once a week with a one-inch line from a fairly substantial stream. Those are both illegal in the eyes of the law, [but] their impacts on stream health are radically different."

Gallegos points to what are known as the "cartel" grows -- massive operations on state, federal or private land that move in and out with little regard for the surrounding ecology. "It's a different game," he says, "and these aren't the same players."

[][][]

Anna Hamilton is one of the old guard. A plainspoken firebrand affectionately dubbed "Anna Banana," she moved to Southern Humboldt in the 1970s, part of the fabled back-to-the-land migration that planted the seeds of today's pot culture. While she still grows under a medical 215 permit, she doesn't like the direction the industry is headed -- specifically when it comes to disregard for natural resources.

"If I had my way we'd be out of Afghanistan and they'd send the National Guard out to walk the river and inspect every pump," she says -- and it doesn't sound like she's kidding. "On one hand, it's fascism. On the other hand, the real war is the environment."

Hamilton wants to launch a campaign, similar to a recent anti-diesel "stop the spill" effort, that will, in her words, "scare the shit" out of unconscientious water hogs. (She says she hasn't thought of a catchy slogan, but does throw out "Don't Fuck With the Fish.")

Hamilton hopes to mobilize people so effectively that "if you spill dirt in the river and put a straw in, you're going to get complaints from your neighbors, you're going to get snitched off." For years growers have harbored distrust, if not downright disdain, for cops and government officials. Hamilton thinks it's time to change that, to build "a culture of cooperation and a different relationship with the establishment."

"This county has changed so much," she continues. "The people who are enforcing the laws aren't necessarily our adversaries. In some cases they're acting as our advocates."

Fish and Game's Arnold echoes that sentiment. She says she wants people to understand that coming into compliance with state water regulations doesn't mean getting busted. "I don't have the time or regulatory authority to look at anything other than fish and wildlife. I'm only focused on the department's mission when I go out to look at diversions," she says.

Fear, however, isn't the only hurdle. Turning an illegal diversion into a legal one can be complex and arduous, partly because you're dealing with two different permitting agencies: the state Water Resources Control Board and Fish and Game. A lot of people aren't aware of this distinction. As a result, Arnold concedes, most landowners are probably diverting illegally in the eyes of at least one agency, if not both.

Arnold defends the system, pointing out that the water board and her department focus on different aspects of water use — shared rights versus wildlife protection. Still, she acknowledges that the process is cumbersome.

"We're used to getting along on the roads," she says, likening the regulatory labyrinth, perhaps unflatteringly, to dealing with the DMV. "Now we have to get along on the rivers."

[][][]

Of all the people who worry about waning rivers, Tasha McKee, executive director of Sanctuary Forest, is easily among the most optimistic. Not because she denies the severity of the problem, but because she's managed to do something about it.

McKee's focus is the Mattole River, a minor yet critical waterway in Southern Humboldt. While McKee says the Mattole isn't being tapped for any "major, industrial-level grows," plenty of people are pumping from the river. And almost every year, by late summer, the Mattole is in crisis mode, reduced to a trickle between brackish pools.

To curb the effects of human use, Sanctuary Forest launched a storage-tank program in 2004. Funded largely by grant money, the program purchases large tanks for landowners, who fill the tanks during the winter with rainfall and flows tapped from a robust Mattole and use the water during the dry months. Usually starting in mid to late summer, and certainly during the bone-dry slog through September and October, landowners agree not to pump from the river.

A recent tour of one of the tanks revealed an impressive sight: 50,000 gallons of water, buoyed by the recent summer rain, encased in a glistening 50,000 gallon drum, outfitted with a series of safety shutoff valves to prevent accidental draining. The tank, surrounded by brown grass and brush, will later be use to water crops, take showers, flush toilets — everything. And the tanks don't raise property tax valuations, since Sanctuary Forest technically owns them for the first 15 years.

The goal is to end 80 percent of all dry-season diversions on the Mattole. So far, McKee says, the project is about halfway there. And not everyone joining is a private homesteader; this year the program will add Whitethorn Elementary School and Whitethorn Construction to its ranks.

McKee admits some of her project's success is due to its small scale, but says that variations of it could be used anywhere. Indeed, the idea of storing water was championed by everyone from Hamilton to Gallegos.

But, McKee cautions, simply halting diversions isn't enough. She says the problem goes deeper. Literally.

Eight years ago, McKee recalls, she walked a stretch of the Mattole with Fish and Game to inspect pump screens. Along the way, she observed the flow of various tributaries. She fully expected that the most heavily tapped tributaries would be the most meager. "Instead I saw that they were all barely trickling."

The reason, McKee says, is that the ground can't hold water like it once did. Human endeavors -- from roads to logging to overgrazing -- have disrupted the natural hydrology countywide. If the soil is our water tank, we've riddled it with holes.

"Diversions are important," McKee says, "but if we're going to withstand droughts we've got to repair our watershed."

Still, she adds, "we've got to deal with human use [diversions] first, so people don't take all the water."

Greacen agrees. He says that while illegal diversions may not be the biggest drain on the county's rivers and streams, they're "the highest impact that we have real control over."

We can work to improve watershed health, he argues, but "even if we invested a ton of money, it's going to take time for that to filter out. Meanwhile water diversions we can do something about right away."

[][][]

Storage tank programs and educational outreach are all well and good, but few believe they'll solve, or even damp down, the problem. "A lot of people, regardless of their legal situation, are doing the right thing because they care about the place and they care about the fish," says Greacen. "At the same time, a small minority are going huge [and] having the vast majority of the impacts."

Watershed monitor Josh Smith concurs. "The big-time growers who are just greedy aren't changing their ways," he says. "The people having the biggest impact on water don't care and aren't going to care."

Unless, of course, the profit motive is removed.

You can't have a discussion about any aspect of the marijuana industry -- including water diversions -- without talking about legalization. It's a thorny topic, and a huge one. But when it comes to water alone, there's a pretty clear consensus among scientists and even some members of law enforcement: decriminalization would help. A lot.

"I would assume it would come with some sort of regulation, like private forestry," says Smith. "Rules about when, where and how you can grow, how much water you can draw, best management practices."

In an unregulated black market, growers have no incentive to be conscientious. In fact, those who sack the land for maximum profit are at a competitive advantage. Yank the industry out of the shadows and the darkest elements would disappear. Maybe.

"There will always be outlaws, people who want to rape and pillage the environment," says Gallegos. "[But] you can bring most people into the fold and reduce the burden on the community."

While we hold our collective breath (or not) the best answer may be to go after the worst environmental offenders, and hope the fear motivates — and trickles down. "I think it's absolutely important to target people who are operating in a way, in whatever industry, that creates the potential for significant harms to public trust values like endangered fish, water quality, ecosystem health," says Greacen. "Those aren't buzz phrases, they're real, tangible things that hang in the balance."

Comments (12)

Showing 1-12 of 12