On Tuesday, Dec. 19, 2000, shuttle driver Ross Vitalie, the owner of Door to Door Airporter, Inc., in Eureka, picked up his fare — a slight figure in his early 50s with an odd, gruff manner of speaking and peculiar facial tics — at what was then known simply as the Arcata Airport.

The dark-haired and affable Vitalie then headed roughly 15 miles south on U.S. Highway 101 to Harper Motors, a Ford dealership located just north of Eureka, where his passenger picked up some keys for his car, which was stored in long-term parking at the airport. Vitalie drove him back. The round trip took little more than a half-hour.

Vitalie's passenger had been a regular customer over the past half-decade. "You could say he was a little bit strange," said Vitalie, a muscular six-footer who studied martial arts in college. "And for his size he could be very demanding."

Airport records would later indicate that Vitalie's passenger had stored his car in long-term parking often over several years. Vitalie dropped off his passenger — whom he called "Robert" or "Bob" — at the airport and bid him adieu, and records indicate the man removed his car from the airport lot that afternoon. "He was a loner," Vitalie recalls. "The only thing I remember was him asking what was going on around town whenever he returned. He'd want to know if anything was going on with the police department."

Vitalie's fare that day was none other than Robert Durst, the quirky and, perhaps, deadly scion of a Manhattan real estate dynasty who was the subject of the documentary series, The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, which aired on HBO this past winter.

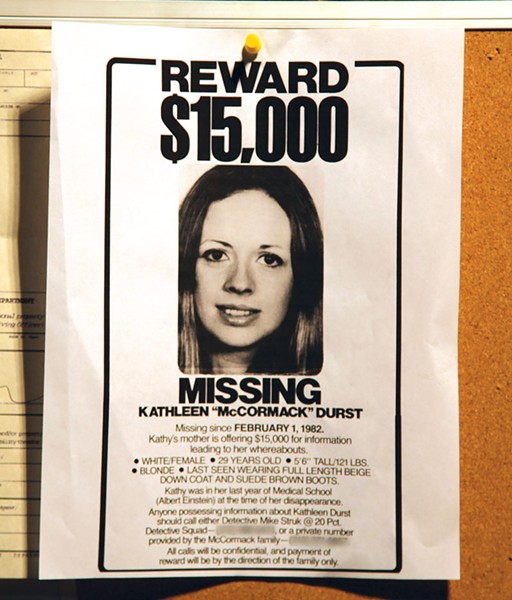

Durst has long been a suspect in the disappearance of his wife, Kathie McCormack Durst, who went missing from their suburban New York home in 1982 and hasn't been seen since; he has recently been charged with the 2000 murder of his close friend, Susan Berman, in Los Angeles; and he was found not guilty by reason of self defense of murdering his neighbor, Morris Black, in 2001, after Black's dismembered body was found in Galveston Bay, off the coast of Texas.

Durst's saga and the mysterious deaths that surround him have become, in recent months, part of the national cultural fabric. Durst has emerged as a kind of celebrity, an accused killer turned sensation. That he was found not guilty of murdering Black, whose severed head was never recovered, has seemingly only added to Durst's creepy celebrity status and mystique.

Today, the 72-year-old Durst is ailing, incarcerated in the St. Charles Parish jail in New Orleans while facing federal gun charges. After that process plays itself out, he'll be facing extradition proceedings to bring him back to Los Angeles to face first-degree murder charges for the killing of Berman — a murder that Los Angeles authorities believe began with a drive from Humboldt County shortly after Durst picked up the keys to his car in Eureka that day in December.

Robert Durst first relocated to the seaside town of Trinidad in late 1994 or early 1995, shortly after his father, Seymour Durst, passed him over for his younger brother Douglas as head of the family's billion-dollar high-rise empire. In The Jinx, it was portrayed as though Robert Durst never wanted to serve as head of the family business, but that's one of many false narratives established by Durst after the fact.

Those who knew him saw it differently. They say Durst was livid about being bypassed by his younger sibling and that — angry and bitter — he had blown up in the plush Manhattan offices of the Durst Organization when he had been told the news. Durst had come to the Emerald Triangle — where pot was plentiful and accessible, and where he could go essentially unrecognized — to get away from his father and brother, to break away from the long arm of his family's influence.

According to records in the Humboldt County Recorder's Office, Durst purchased a three-story ocean-view home in Trinidad from Diane Bueche in June of 1995. "It was very rural," Durst would tell The Jinx director Andrew Jarecki about Trinidad in an interview for the film. "Very pretty."

Located on the corner of Van Wycke and Galindo streets, Durst's residence — with wall-to-wall decking and full-length picture windows on each level — afforded sweeping views of Trinidad's waterfront.

Bueche lived directly next door on Van Wycke. The outgoing, well-off Bueche was "a bon vivant" to her friends (many called her "Bo"). She owned and managed several properties in Humboldt and Trinity counties, and quickly became Durst's friend, confidante and social guide to the North Coast. They went out to dinner, movies and cultural events.

"Bobby" Durst, as he was most frequently known, generally kept to himself, but he had a surprising charm around women. They seemed to hover over him, guarding him, maybe even wanting to "mother him," according to one friend. He was receptive to such affection. His own mother had committed suicide when he was 7, though not, as he would often claim, directly in front of him. Durst liked to stretch the truth on that story, too.

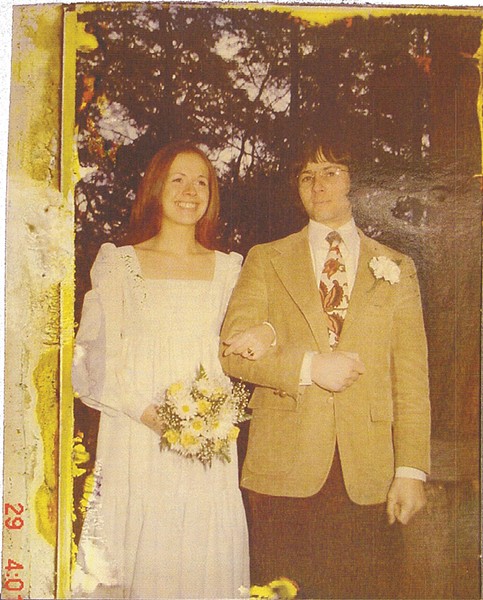

His first wife Kathie, was a beautiful, bright 19-year-old when they met. By the time she disappeared, Durst had taken up with Prudence Farrow, the younger sister of actress Mia and the subject of the Beatles' White Album song, "Dear Prudence." Some suspected that Bueche and Durst were an item in Trinidad, but no one seems to have known for sure. One police report, drafted in 2003, asserts that Durst only had sex with prostitutes since the disappearance of Kathie in 1982.

There's no indication that Bueche and Durst's relationship was more than platonic, though they kept in close contact with each other, even when one of them was out of town. Bueche would later say that they stayed in touch by phone, email, fax and letters. Durst, who still used his Manhattan letterhead for business communication, had stationery printed with his Trinidad address on it for local and personal correspondence.

In one letter Durst sent to Bueche (a copy of which was provided to the Journal by Matt Birkbeck, author of A Deadly Secret: The Bizarre and Chilling Story of Robert Durst), he said that he had "so much fucking energy these days I feel like the top of my head is coming off." He cryptically mentioned rearranging the furniture in Bueche's bedroom and upgrading his burglar alarm. He asked rhetorically, "Do you know it is illegal to shoot your pistol in town even in self defense[?]"

In another handwritten note that Durst faxed to Bueche, he declared: "I'd love to joust with you, but you might crush me like a bug. However, if you enjoy crushing bugs, call me. ... Maybe I'll get to bite you real good before I'm cornered."

Those who knew Durst in Trinidad recall an odd little man ("a weird, weird dude," said one; "a very strange guy" and "spooky," said another) who threw his money around with a small coterie of acquaintances and talked big, but whose stories never quite added up.

Durst had told Bueche and others that he had a daughter (he did not) and that he had planned to develop property in Big Lagoon, only to run afoul of the California Coastal Commission. There's no record of that. For a while he kept an office in Eureka's Old Town, on E Street, though what he actually did there is anyone's guess. At one point he claimed he was a botanist for the Pacific Lumber Company. At other times, he said he was an insurance investigator or a rare metals expert or a writer for the Wall Street Journal. None of it was true.

Durst was essentially computer illiterate and incapable of typing when he arrived in Humboldt. He put up an advertisement for a computer tech at Humboldt State University's career center and eventually hired a student, Michael Glass. Like most who encountered Durst in Humboldt County, Glass described him as being an "odd duck" and "eccentric."

Because Durst was sensitive to the noise from the fans in his computer, Glass was asked to develop a routing signal from the main computer "box" on the ground floor to Durst's office on the third floor, which required long cables and a rare boosting device. Glass said Durst once asked him if he knew anything about Durst's family in New York (Glass did not), but didn't discuss either his private or business life with Glass, who was then in his early 20s.

One of Glass's memories stands out: Durst was thoroughly infatuated with Pixar's computer-animated blockbuster, Toy Story, which was released in 1995, right around the time Durst arrived in Humboldt. Durst wanted all the imagery on his computer — the screen saver, etc. — related to Toy Story. Durst, Glass recalls, powerfully identified with the film.

One pattern of Durst's that was continued in Trinidad was that he hired a young, high-school aged girl to serve as his housekeeper (he had done the same in New York). While law enforcement profiles of Durst usually identify his interest in older women close to his age (like Bueche), he always had young women around him, too. Durst's housekeeper in Trinidad had a key to his house so she could come by when Durst wasn't there to clean up after him and his habit of throwing candy to the floor if he didn't like it.

Records in Humboldt County indicate that in 1996 Durst provided a loan of $70,000 to a family in Trinidad for the down payment on a home, not far from an ocean-view inn that the family ran and at which Durst stayed from time to time when he was first exploring the area. They described him as "extremely polite," having "good manners," and being "quiet" and "always busy." They had little contact with Durst, other than arranging the loan, and Durst charged them 15 percent interest, which they paid monthly. Within a few years they were able to secure a bank loan and paid Durst off. They had no other contact with him.

In January of 1999, Durst formed a business partnership with another couple in McKinleyville, providing them with seed money for their venture, and he filed a Uniform Commercial Code document with the California Secretary of State. Other records obtained by investigators indicate that he was involved in an offshore financial consulting firm. But whatever big dreams Robert Durst had in Northern California never came to fruition.

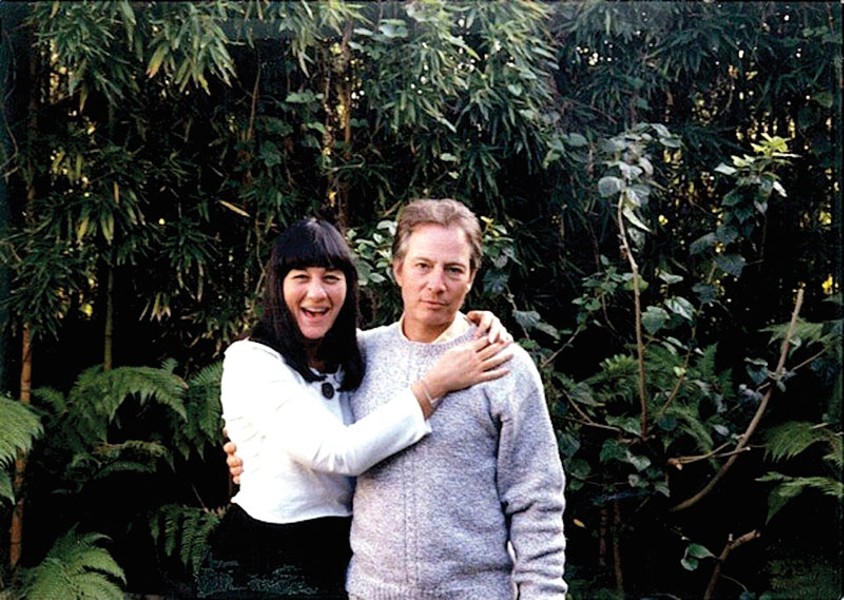

The same December day that Durst rode with Ross Vitalie to and from the Arcata Airport, his intimate and longtime friend, Susan Berman, a struggling writer in Los Angeles, had a conversation with one of her closest friends, actress Kim Lankford, who would later recall that Berman was especially hyper that day. In an interview with New York, Lankford said that Berman told her she was about to break a big story "that was going to blow the top off things."

"Susie," said her friends, was always on the verge of something, always a handful. She was the daughter of a Las Vegas mobster, Dave Berman — also known as "Davie the Jew" — a close associate of the legendary Vegas mafioso Bugsy Siegel, who had been assassinated by rival gangsters in 1947. Lankford presumed that her friend's big revelation had something to do with mob history, maybe about who had killed Siegel.

Berman had met Durst at UCLA in the late 1960s and the two had reportedly bonded over losing a parent to violence in their childhoods. By 2000, Berman had relocated to Los Angeles and was begging her friends for money.

When Durst's wife Kathie went missing in 1982, Berman had served as Durst's spokesperson. Many now believe she also may have helped Durst mislead investigators. While they were no longer as close as they once were, sometime in the fall of 2000 after investigators in New York had kick-started a new investigation into Kathie's disappearance, Durst sent Berman, now living in a run-down bungalow in Beverly Hills, two checks for $25,000 each — a $50,000 gift, he made clear, not a loan.

On the morning of Dec. 20, 2000 — the day after Vitalie had picked him up at the airport — Durst placed a pair of calls from pay phones located in Garberville, roughly 90 miles south of Trinidad, according to lead Los Angeles investigator Paul Coulter in The Jinx. His cell phone had been turned off, but Durst was heading south.

Four days later, on Christmas Eve, Berman was found face down in a pool of blood on her bedroom floor, executed by a single shot from a 9mm pistol to the back of her head. Since there had been no forced entry into Berman's home, investigators immediately speculated that whoever killed the mobster's daughter knew her.

On Dec. 27, the Beverly Hills Police Department received an anonymous note, postmarked Dec. 23 in Marina del Rey, indicating that there was a "cadaver" at Berman's address on Benedict Canyon Drive. The note may have been anonymous, but the author left a telltale sign, spelling "Beverley Hills" incorrectly. Prior to the killing, Durst had written a letter with similar handwriting to Berman. In it, he had spelled "Beverley Hills" with an extra "e."

The timing of Robert Durst's December 2000 drive from Humboldt County to Los Angeles came as no surprise to investigators who followed the Durst case closely. On Halloween of 2000, Durst received a tip that law enforcement officials in New York had re-opened the case of Kathie Durst's disappearance 18 years earlier.

The heat was back on. On Nov. 15, Durst called an apartment owner in Galveston, Texas, on behalf of a "deaf-mute woman," Dorothy Ciner (one of Durst's many aliases), looking to rent a two-room apartment for $300 per month. Durst was setting up shop in Galveston even before he had cleared out of Humboldt County.

Durst's erratic behavior during this time was also noted in Trinidad, where his confidante Diane Bueche began to feel uneasy. At first she defended Durst when television crews came to town in the spring of 2001 for the ABC shows Vanished and Prime Time, saying that Durst was "the victim of a ruthless press." Durst had suggested that she watch Unsolved Mysteries, which featured a segment on his missing wife. Perhaps, Bueche later speculated, that was to deter her concern.

By the fall of 2001, however, when Durst went on the lam following the killing of Morris Black, Bueche became more than a little concerned. There had been an alleged sighting of Durst at Bueche's campground on the Trinity River, although this was never confirmed. Bueche eventually contacted Journal publisher Judy Hodgson to tell her the Durst story. She told Hodgson that she was "ill and dying of cancer" and that she "felt a little duped or stupid for originally taking Durst's side."

A few months later, in February of 2002, a psychic by the name of Barbara Stamps told the New York Post that she began "picking up on dark energy" at Durst's former Trinidad home and "had very strong feelings that a murder had been committed" there, directly next door to Bueche's residence. Stamps said that she had "mental images" of the home as early as May 16, 2000 — long before the killings of Berman and Black.

Once again, Durst's name was in the headlines and residents in Trinidad became anxious. Many worried that they had recently had a murderer in their midst. Only months after the psychic identified Durst's home, Diane Bueche was found dead in the master bedroom next door. She had committed suicide, firing a single shot through her head with a Smith & Wesson .357 revolver. The coroner's report indicated that she had been despondent over a cancer diagnosis. Durst was in custody in Texas at the time.

Years earlier, Durst had been arrested in Mendocino County for driving under the influence and possession of marijuana. This arrest went unreported in media coverage of Durst.On May 11, 1995, Durst was pulled over in Mendocino after drinking a bottle of wine at the upscale Beaujolais Restaurant, Officers found marijuana and $3,700 in cash in Durst's trunk, and he failed a series of field sobriety tests. Then, with phrasing familiar to anyone who watched The Jinx, Durst uttered to a cop that "the money and marijuana is mine and I have always smoked it, even as a kid. So what's the big deal?"

After he left the Durst Organization in 1994, Durst had assumed an even more bizarre lifestyle than the one he maintained in New York. He had residences all over the country: in New York, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and California. He liked frequenting the skid row neighborhoods in various cities (including Eureka), often hanging out with the homeless and down and out.

In addition to his home in Trinidad, Durst also owned two upscale townhouses in San Francisco. "He'd fly from Texas to California to Louisiana then back to Florida then Texas again," said Cody Cazalas, the lanky mustachioed investigator from Galveston, Texas, who appeared in The Jinx. "He was extremely mobile. And very secretive about his movements. Two or three days was about it in any one place. He was all over the charts."

Robert Durst had become a very difficult guy to track down.

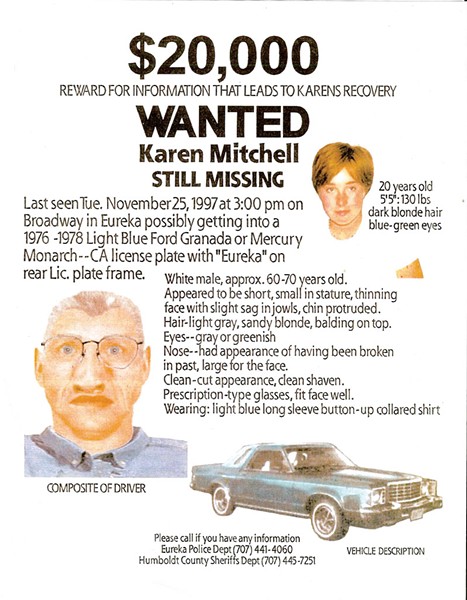

Little more than two years after Durst was arrested in Mendocino and had settled into his ocean-view digs in Trinidad, a 16-year-old high school student from Eureka — Karen Marie Mitchell — was declared missing after visiting her aunt's shoe store at the Bayshore Mall on the south side of town. The Mitchell case both captivated and galvanized the community. Over the next several years, numerous leads were exhausted, and several suspects were identified, though nothing came to fruition.

Although it's not clear when Durst first came onto the radar of Eureka investigators, newspaper records indicate Mitchell's aunt and legal guardian Annie Casper (with whom she was residing at the time of her disappearance), first publicly identified Durst as a suspect in the Mitchell case in December of 2001. "[Durst's] been in our store twice, which I thought was kind of odd," Casper was quoted as saying in a newspaper. On at least one occasion when Durst was in Casper's store, according to a former store employee, he was dressed as a woman.

According to multiple sources close to the case, EPD investigators had their eyes on another suspect, a Humboldt County trucker named Wayne Adam Ford, who eventually confessed to killing four women (but adamantly denied killing Mitchell). Moreover, federal investigators apparently told local law enforcement that flight manifests indicated Durst wasn't in Eureka on the day Mitchell went missing. (Later investigators discovered that Durst may have been covering his tracks by purchasing airline tickets that he didn't use and flying under false names.)

Shortly before Mitchell went missing in 1997, there was another disappearance of a young woman in Northern California, Kristen Modafferi, an 18-year-old student from North Carolina visiting the Bay Area for the summer. One of the suspects in the Modafferi case fit a similar profile to Durst, particularly in respect to cross-dressing and prowling around homeless shelters. Oakland Police investigators felt there might be a connection.

Although Bay Area investigators didn't have sufficient evidence to pursue Durst in respect to Modafferi's disappearance, they felt that there was reason to pursue Durst further in the Karen Mitchell's case. According to A Deadly Secret, the East Bay investigators believed that Durst was in Humboldt County on Nov. 25, 1997, the day of Mitchell's disappearance. In 2003 they subpoenaed credit card and Federal Express records that seemed to confirm that belief.

One of the investigators, John Bradley, interviewed a woman then incarcerated in a San Francisco jail, Sheli C., who had lived in Humboldt County during the same period that Durst was living in Trinidad. A drug addict and a prostitute, Sheli had been arrested on narcotics charges. Bradley had a hunch that she might know something about the Mitchell disappearance. She didn't.

But when Bradley showed Sheli a picture of Durst, she recognized him immediately from Eureka, where, she said, Durst had frequented a homeless shelter only a couple of blocks from the office he kept in Old Town. "Karen Mitchell's aunt and guardian," Bradley declared in a report from 2003, "told me Mitchell volunteered at [a shelter in Old Town] for a brief period."

Sheli said that Durst's "pattern" was to hang around the shelter for a while, disappear for a couple of months, "then he would return to loitering around the homeless shelter."

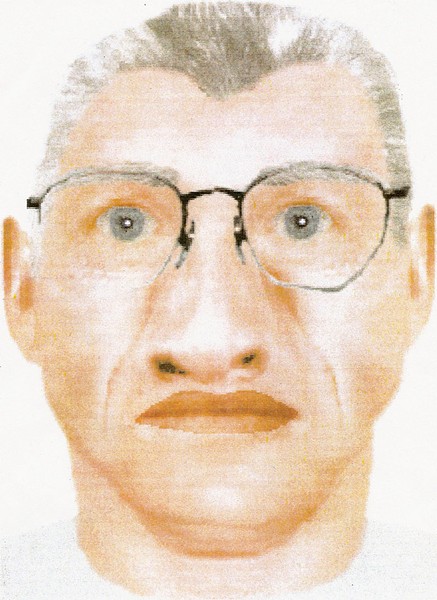

There had also been a composite sketch drawn of someone who may have been driving a car that Mitchell got into the day of her disappearance. A witness, Randell J. Gomes, had stepped forward months after the girl's disappearance, and the sketch looked like Durst — down to his oversized wire-rimmed glasses — so much so that Bradley believed the informant had to have known Durst.

The last thing Sheli said to Bradley was that "weird people get tired of doing normal stuff." The line struck a chord with Bradley. Then Sheli went on the lam — and Gomes, according to a police report, left town for Idaho. The case went cold.

In the aftermath of Durst's arrest last month, Andy Mills, the city's recently appointed police chief, has quietly reopened the Karen Mitchell case.

Mills describes the Mitchell investigation as "reinvigorated and active," and said that while he was unable to identify any new evidence involving Durst, that Durst was in "the mix" as a suspect. More recently, Mills told me that that there was a renewed collaboration between the EPD and one of the Bay Area investigative units.

The FBI has also assembled an unofficial nationwide task force specifically looking at a multitude of unsolved murders and disappearances where Durst has lived, stretching back more than 40 years. Mills said EPD is collaborating in this effort, as well.

Several law enforcement officials think Durst may be a serial killer. In the cases of his wife Kathie, Susan Berman and Morris Black, he may have had overt motives to kill them. With the others, the motivations would be vague at best.

During the Morris Black investigation, Det. Cazalas openly speculated that the murderer "had done this before." The detective believes with certainty that Durst killed his wife and Susan Berman, along with Morris Black. Would it would surprise him if Durst had killed more people? "No," he said with a long drawn-out pause. "No, no it wouldn't."

Bradley, the Bay Area investigator, also believes that Durst has killed other victims. "I reasonably believe Durst was a serial killer," he wrote in an official report in 2004. "Others believe Durst only kills people he knows and with whom he has become enraged. I counter that his comfort level with killing is so secure, he kills strangers for practice then people directly connected to him and just does not worry about discovery."

It seems that Robert Durst is always trying to get caught. He hinted at as much in The Jinx. When asked about the letter addressed to the "Beverley Hills" Police Department on the day of Berman's murder — the letter authorities now believe he wrote — Durst acknowledged that the killer was "taking a big risk. You're sending a letter to police that only the killer could have written."

Similarly, Durst left mail with his address on it, along with parts of Morris Black's body, in garbage bags in Galveston Bay; he told lies to New York City detectives about his wife's disappearance that were easily discovered; he ripped off some band-aids and a hoagie at a market in Pennsylvania when he had $500 in cash in his pocket. Most recently, he urinated on some candy bars in a convenience store while security cameras recorded his activities.

Durst always has a counter-narrative to explain his actions. It's a cat-and-mouse game he seemingly likes to play. How else does one explain his participating in a film project that ultimately resulted in his arrest?

Durst's defense attorneys have repeatedly denied his involvement in all of these murders. In a recent motion filed in New Orleans, his defense team challenged the legality of the search warrant that led to his current incarceration and they have also contested the handwriting evidence linking him to Berman's killing in Los Angeles.

At the end of The Jinx, in which he reportedly provided the producers 25 hours of interviews, Durst stepped into a bathroom and mutters into a hot microphone what many have taken as a rambling confession: "There it is. You're caught. You're right, of course. But you can't imagine. Arrest him. ... What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course."

Whether he's found guilty in a court of law, however, remains to be seen. His flight to the Arcata Airport in December of 2000 and the Garberville phone calls will figure prominently during his future trial in Los Angeles. But when it comes to Robert Durst and a courtroom — where mere speculation is stripped down to what's provable beyond a reasonable doubt — nothing is certain. Durst has beaten a murder rap once before.

Geoffrey Dunn is an award-winning filmmaker and investigative journalist from Santa Cruz. He wrote and directed the documentary film Calypso Dreams and is the author of The Lies of Sarah Palin.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2