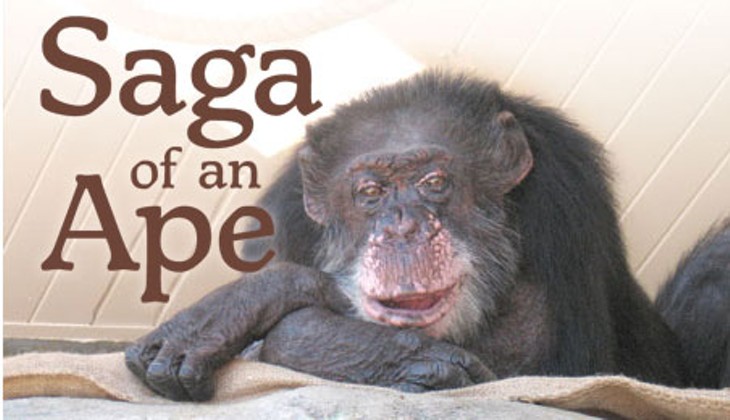

When the Sequoia Park Zoo’s oldest and most popular animal rejected food and water and struggled to breathe for a second day, his caretakers made an announcement that riveted the Eureka community: Bill the Chimp was dying.

The press release declaring that the 61-year-old chimpanzee was “gravely ill” got instant responses from reporters, and when the news broke on June 26 it magnetized emotional reactions from the many people who considered Bill their longtime friend. Finding the zoo closed as its staff tended to the dying chimp, well-wishers hung cards and ribbons on its front gate, but by the end of the day, the decision to euthanize the city’s favorite zoo resident was deemed unavoidable.

Perhaps the suddenness of Bill’s death made it hit harder. The zoo had begun a renovation of his exhibit space barely a week earlier, a project that would have brought the chimp’s living conditions somewhat closer to modern professional standards. Not long before that, he’d been visited by famed primatologist Jane Goodall, who spent about 45 minutes with him and concluded that he was in good condition. Undiagnosed heart disease was about to intensify, however, forcing the zoo’s staff members to make the most painful decision of their lives. And those who’d only known Bill as zoo visitors shared the sense of loss, summarized in a Times-Standard newspaper editorial. “He Was One of Us,” its title proclaimed.

But Bill the Chimp wasn’t a human being, although through twists of circumstance he became involved in human society and took on various roles in it. Considered a member of the community, he was also its captive. In many ways nothing is as it seems with Bill. His history and his relationships with people reveal a lot about him, however, most of it surprising.

Into the ring

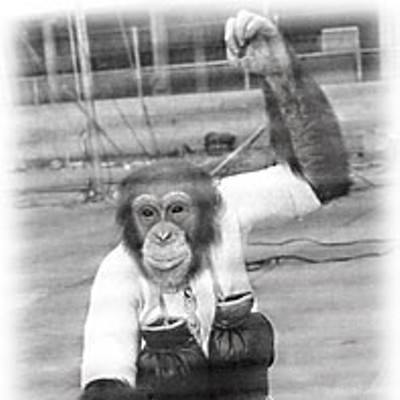

In the summer of 1957, Eureka’s biggest event was a boxing match featuring a fighter known as Billy the Champ. It was a rigged fight, like all of them had been, but this would be the only one he’d ever lose. A “retirement” to the city’s zoo awaited the 11-year-old chimpanzee, who’d become too savage for the circus.

Bill the Chimp’s initiation to human society likely began years earlier in a Central African jungle. Chimpanzees and other exotic wild animals were rarely bred in captivity then, and after being captured in the jungle they were marketed by animal dealers to circuses, research labs and collectors. Infant chimpanzees were of high value and were often obtained through the killing of their parents. The circumstances of Bill’s capture may never be discovered, but by the early 1950s, he was performing in England with the Bertram Mills Circus, the British equivalent of Ringling Brothers. He formed one of his closest human bonds there, with a Dutch animal trainer named Willy Lenz.

Lenz joined a circus in Holland when he was 17 years old, and animal training became his specialty. After establishing himself internationally working with brown bears in various circuses, he was hired by Bertram Mills to train its team of six chimps. His wife, Ann, a trapeze artist and high-wire walker, joined him and together they helmed one of Bertram Mills’ most popular attractions.

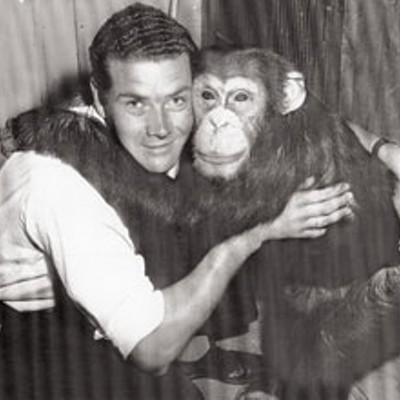

Billy and the other chimps did somersaults on trampolines, rode bicycles, beat on drums and pretended to play musical instruments in a mariachi band, but the act that really got crowds going was the chimp boxing match. The elaborate spectacle featured chimps playing the roles of boxers, referees and nurses. Lenz chose Billy and another chimp, Pepe, as the fighters, and dubbed them “world chimpions of the ring” in his advertising. Nicknamed “The Professor” for his smarts, Billy was one of the troupe’s most engaging performers and best fit the role of The Champ. The matches highlighted Bertram Mills’ annual Christmas show at the Olympia in London, where Billy vanquished Pepe in front of audiences that included Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret.

A half-century later, Ann and Willy still remember one of the smartest and most appealing chimps they’d ever met. In a telephone interview from their home in North Carolina, they described the origin of a habit that endeared Billy to zoo visitors in Eureka decades later -- the “raspberry” noise he made, which they trained him to do after Pepe fell to the mat in mock knockouts.

“Billy was always the one who was the champion and then the ringmaster came to him and say to Billy, ‘Billy, what do you think of him as a boxer,’ and he said, ‘pftttttt’ ... you know, and that’s why he has those raspberries,” said Willy. “And that went over very good with the people.”

With Billy as its charismatic lead, the act was ready for import to America with the Pollack Brothers Circus. On a boat ride from England to New York City’s Radio City Music Hall, Billy lived up to his nickname. The chimps were held in cages in the boat’s storage room but Billy had other plans.

“I was not feeling too good on that boat, you know, and they knocked on the door and they said, ‘Oh boy, you better go look in the mail room, there’s something going on in there,’” Willy said. “Well, I opened the door and all the chimps were out in the mail room and they were eating bananas and throwing all sorts of things around.” Examining the cages, Lenz surmised what had happened. Billy had burst out of his cage and grabbed a set of keys hanging on the wall, using them to let out the rest of the chimps.

Billy was also something of a ladies man. “We were working one time in a show, and a lady came close by, and he liked that lady,” Ann said. “And she had a zipper up her back, you know, from her dress, and he liked to open the zipper -- up and down and up and down. I mean, that was Bill.”

But the likeable chimp would soon be a threat.

Knocked out

Sexual maturity triggers sharp changes in a chimp’s behavior and physical power. The Champ eventually lived up to his role, asserting himself as a dominant male. By the time the circus reached Eureka, he was performing at the end of a leash. Billy the Champ was too dangerous for Ann and Willy to keep.

“He goes against you, you know,” said Willy, “He wants to have the upper hand, and instead of going against him, let’s say, ‘It was nice time and let’s forget it,’ and I’ll find him a good place. Otherwise, you have to go to rough stuff and I don’t like that.”

“And if something happens, then we are to blame,” Ann added. “So we should know when it makes sense to stop.”

The timing of the transformation led to Billy’s residency here. “We were playing in town, at the fairgrounds, and then I got acquainted with one of those photographers from the newspaper,” said Willy. “And then we start talking and I said, ‘Well, that chimp, we have to do away with him,’ and then he said, ‘Boy, that would be something for our zoo’ -- and that is the way we got the whole thing going.”

In the near-legendary stream of events that followed, a media-driven effort to raise the $350 to buy Billy for the zoo was banked with the pocket money of city schoolchildren. Lots of fanfare preceded the move to his new home, and his final boxing match was a big draw, with an outcome that set up his exit from the ring and circus life. “You watched him take his K.O. like a true champion,” a July 12, 1957, report in the Humboldt Standard told readers.

His arrival at the zoo was heralded with a massively attended celebration and an honor from city officials. “Bill Devours Key to Eureka,” read a Humboldt Standard headline, referring to the key-shaped cookie he’d been presented with. A Dixieland band provided upbeat music, dedicating a song called “Down in Monkey Town” to Bill. It seemed that the city welcomed a new member of the community, but the reality of the transition went unreported until many years later.

In a letter Ann wrote to the zoo’s management last year objecting to its description of Bill being “rescued” from the circus, she described his first day in his permanent home. She and Willy had parked their 18-foot chimp transport truck at the zoo and all of the chimps were led into Bill’s cage. “We let them play, and then after some time, take one out, then one hour later, another, until Billy was alone and waiting his turn,” Ann said in the letter. “We were parked with our truck and trailer by the fence, and six o’clock in the morning I started the truck, and Bill start crying, and so did we. From that time on, he was alone.”

Ann emphasized that Billy had a social life with other chimpanzees in the circus, and with his trainers. “As you can see, we had a special bond with our chimps,” she wrote. But those bonds were broken by something stronger. “Chimpanzees, at an older age they get, you can’t trust them anymore,” Willy said in the interview. “So, you can’t go against nature.”

‘Complex personality’

The Sequoia Park Zoo was a very different place decades ago. Zookeeping was still in its developmental stages in Eureka. A small zoo is not a good place for chimpanzees, as they need social settings and spaces with natural features and lots of room. Bill the Chimp’s home was basically a steel cage, described in newspaper accounts as 10 feet by 14 feet. His presence at the zoo was challenging from the outset. One Humboldt Standard newspaper account informed that despite signage, “The Champ’s life and health are endangered every day by visitors who feed him or give him things to play with.” Chimpanzees are susceptible to diseases and germs carried by humans, and years later Bill tested positive for Hepatitis A and B.

The zoo had several other animals it probably shouldn’t have, including lions, a Bengal tiger and a polar bear. By the mid-1960s, zoo managers decided to add something else: another chimp. Ziggy, a hand-raised male chimp who’d performed in Las Vegas and ended up in an animal shelter, was introduced to the zoo in the spring of 1966. Bill’s original enclosure had been dismantled and a new one was built, with double compartments for each chimp. Pairing two adult males is risky, and they were enemies from the start.

Their first meeting was observed by former city Community Services Director David McGinty, who worked as a weekend zookeeper at the time. He said each side of the enclosure had a sleeping chamber attached, and Ziggy was let out of his and entered one side of the outer exhibit. McGinty and other workers were preparing Bill’s side of the exhibit when he unexpectedly broke out of his inner chamber and loped past them. As McGinty and the others scurried out of the cage, Bill and Ziggy had their first meeting.

“Bill probably acted the way he would in the wild,” McGinty said. “He did not know who this strange chimp was in the next cage over. Bill was very independent and he was always the master.” The two chimps sprang at each other, gripping the partition, howling and showing teeth. “They were face to face,” McGinty said, adding that Bill probably would have tried to kill Ziggy if the divider hadn’t been there.

So began a confrontational relationship that never warmed. When Ziggy died of liver cancer in 1996, Bill seemed glad to be rid of his adversary, and now he had the exhibit and its audience to himself. The two chimps had developed contrasting personalities, Ziggy’s being less demonstrative, and visitors gave Bill more attention. He commanded it, often by flinging his turds at people. They’d either find it amusing or run screaming, and either way, the assertive chimp was able to manipulate reactions.

McGinty’s memories of Bill vary. “He could be very loving if he wanted to be,” he said. “He had a very complex personality and his range of behavior was incredible.” Bill particularly enjoyed human interaction early in the morning. “He liked a nice hot cup of tea in the morning, and he’d drink it like you and I would,” said McGinty. “It was like having tea or coffee with a buddy.”

Other substances probably found their way to Bill through visitation. When McGinty worked at the zoo, there was only one full-time zookeeper tending to all the zoo’s animals, and the grounds were unsecured. Visitors had access to them 24 hours a day. Current zoo managers believe it’s likely that people gave Bill and Ziggy cigarettes, and one contributor to a recent Times-Standard online comment page claimed to have witnessed Bill smoking a marijuana joint.

Describing the zoo’s development over time, McGinty portrayed the last 15 years or so of Bill’s life to be the best. “He has had excellent, excellent keepers and a lot more oversight, a lot more caring and concern,” he said. “In the early days, we had what we had. I would characterize the zoo in those days to be a place to go to show your kids animals. Now, it’s much more interpretive and educational.”

Here to stay

Improvements to Bill’s living conditions advanced gradually. Only so much could be done within the zoo’s budgetary and space restraints, however, and even minor upgrades were hard-won. Gretchen Ziegler, the zoo’s current manager, was first hired as head zookeeper in 1995 and found Bill and Ziggy’s conditions to be “a bit shocking.” ( Editor’s note: Full disclosure -- Gretchen Ziegler is reporter Daniel Mintz’s companion. )

Ziegler had worked with all varieties of great apes at the Topeka Zoo in Kansas and wanted to know why Eureka’s chimps were housed in sterile, concrete enclosures, the kind that give zoos a bad name. But a few years after Ziggy’s death, she would inherit the situation herself and balance a desire to give Bill the Chimp something better against factors like his advanced age, his long residency at the zoo and the risks involved with moving him.

The zoo saw a milestone in 1995, gaining accreditation from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which noted the obvious deficiencies with the chimp exhibit but also “recognized the situation we were in,” Ziegler said. It was a scenario that continued to work against the zoo’s modernization. “The hardest thing, bar none, about the management of the zoo was the fact that we had this archaic situation that, by the year, became less acceptable,” said Ziegler. Yet there were positive aspects. Bill’s lack of neurotic behavior and his increasingly strong relationships with staff members made the zoo a reasonable place for him to stay.

In 2003, Ziegler hired Jan Roletto to be Bill’s primary keeper. A former Sequoia Park Zoo intern, Roletto had graduated from Humboldt State University and worked with great apes at bigger zoos in Salt Lake City, Utah and Columbus, Ohio. Roletto’s hiring is part of a gender reversal in the zoo’s staff -- once in the minority, women keepers now form a majority, part of a national trend in the zoo industry. And Roletto said Bill showed an obvious preference for women that was even reflected in his choice of possessions. A golden-haired Barbie doll became his favorite one, and he exercised his curiosity by peeking up its dress.

He also had a foot fetish, and liked women who wore short skirts and boots. In grooming sessions with female keepers, Bill would reach between the bars of his enclosure and seek tactile experiences that inevitably involved bare feet. His tendency to “display,” or assert dominance by making noise and aggressively acting out, was contrasted by his grooming behavior. “If he needed you to move because he wanted to look at something that was on your foot, he would delicately touch it and gently push it in the way that he wanted you to,” said Roletto. “It was never forceful, it was very respectful and sensitive.”

But any contact shared between Bill and his keepers was done through a wall of bars. That necessity was strictly followed until a foggy night in October 2005, when vandals cut open Bill’s cage.

Beyond bars

Roletto got a call from Eureka police late in the night of Oct. 6, 2005, letting her know that Bill was out of his exhibit and had been seen in a neighborhood near the zoo. She sped to the scene, thinking of a previous escape episode at another zoo. In the late 1990s, she was working at the Hogle Zoo in Salt Lake City when three chimpanzees got out of their enclosure because a keeper left a gate unlocked. Physical characteristics can set off aggressive responses in chimps, and they may hone in on things that mark people as being different, like disabilities. The chimps at Hogle immediately went on the hunt for a volunteer who appeared mentally disabled, and found him inside a zoo building. They savagely attacked him, severely disfiguring his face and hands. Two of the three chimps had to be shot and killed.

Arriving where Bill had been seen, Roletto found police in the area of a backyard bordering an alley near W Street. Roletto told them she’d try to coax Bill out of the yard. She took a risk, as even people familiar to chimps can be attacked. “I told the police officer, ‘Get about 20 feet away from me and don’t get any closer, but if you hear me screaming, come running,’” she said.

She heard a rustling sound in the backyard, and opened its gate, softly calling Bill’s name. “I slowly opened up the door, and there he was, just standing right in front of me,” said Roletto. She crouched down, ready to curl into a fetal position in case Bill attacked. He didn’t. “I was floored, he just came over and he had a very soft hoot, his eyes had recognition and he just hugged me, and smelled me. I don’t remember being scared after that, because it was either going to happen then or not at all.”

Roletto told Bill it was late and they had to go home. She took his hand and they started walking through swaths of fog toward the zoo. Ziegler had just gotten there to load a tranquilizer dart gun in case things went wrong. The zoo entrance had been remodeled since Bill’s previous escapes over the years, and she knew it would disorient him. When she left the zoo and got out onto W Street, she heard Roletto calling, “Gretchen, stand there so Bill can see you, he doesn’t want to go in!”

Ziegler said Bill “made a beeline toward me” when he saw her from across the street. “It was the most surreal thing I had ever experienced, with the fog and the time of night and a chimpanzee at my side, for the first time without a barrier between us. All I could do is stand there and talk softly and encouragingly to Bill, hoping it would all go well.” It did -- Bill hugged her leg and acted submissively, focusing on her feet. Ziegler obliged him by taking off her shoes and rubbing his shoulders. Bill took her hand and Roletto joined them, and all three entered the zoo.

Gradually and after a series of grooming sessions, Bill complied with his keepers’ suggestions and went back into the enclosed “night room” within his exhibit. Things were back to normal but would never be the same. “After that, I told Gretchen, ‘If Bill is ever on his way out, you can just clear me of all insurance claims, because I’m going in with him,” Roletto said. “I told her, ‘I don’t want him to be alone when he dies.’”

‘Going to Africa’

Eight months later, in June 2006, Bill’s 60th birthday was celebrated at the zoo with the unveiling of a statue of himself and the announcement of a $100,000 renovation of his exhibit. It would be an eventful year, as he’d also meet Jane Goodall, who visited him prior to giving a lecture at Humboldt State University. When some of the students there pressured her to agree that Bill should be moved to a chimp sanctuary, Goodall told them what they didn’t want to hear -- that keeping him at his longtime home was best.

The zoo’s centennial this year would have coincided with Bill’s 50th anniversary there. But soon after construction on his exhibit started, a longtime respiratory condition suddenly worsened. Although his raspy breathing tended to flare and subside, this episode was more serious and, as discovered later, was actually caused by fluid pressure on the lungs from heart disease. His caretakers became alarmed when his tongue turned blue. Then he refused food.

Going into the last weekend in June, Bill stopped sleeping in his night house. He took medication but his condition worsened. “He spent the days at the top of his exhibit, just looking out at the zoo,” Ziegler said. The medicine became harder to administer, and had to be mixed into special treats like soda pop. And by the end of the weekend, Bill’s medicine was morphine.

He was dying, and the staff struggled with the realization that the process might have to be helped along. “At this point, he was just gasping for breath and having to position his body so he could get as much air as he could -- it was extremely uncomfortable for him,” said Ziegler. “He was exhausted, and we knew he couldn’t sleep very well. We could see his weariness grow every day.” Eventually, he couldn’t make it down from the upper platform anymore. “Jan finally said, ‘Look, the only way I can bring him water or coax him to take his meds is for me to go in with him,’” said Ziegler. She agreed to it, and went in with Roletto. “Even then, we felt we needed to be cautious,” Ziegler continued. “But Bill was cool, he was out of it but pretty interested that we were actually coming in -- he looked at us as if to say, ‘Wow, what are you doing?’ He let us give him water and some of the meds. He was always so trusting about what we wanted to do, even though we wanted him to take some funny tasting things. He was always so patient with us.”

They doubted whether he’d make it through the weekend but he did. After another rough day, his lips were blue and his condition “was worsening by the hour,” said Ziegler. The staff had been talking about how euthanasia would be carried out, and now its necessity was clear. At about 7 p.m. on June 26, Ziegler, Roletto and a veterinary team gathered around Bill. They gave him an initial oral dose of Telazol, an anesthetic. He became groggy. Roletto held his head and his hand. Ziegler tried to give him a follow-up injection of the anesthetic, but Bill swung his arm away. The vet tech volunteered to do it and Ziegler left and returned a few moments later. Roletto said that she also “lost it a little bit” and started to cry, something she’d held back so Bill wouldn’t be unnerved. But now he was going under. “I just wanted him to go to sleep, so I held his hands and I said, ‘Go to sleep, babe, go to sleep, you’re going to go to Africa,’” she said. “To be there at the end and to have him holding my hands meant a lot -- I hope it meant something for him. I didn’t want him to be alone. And he had Gretchen there ... I just wanted the last thing he saw to be the keepers, and to have that love around him.”

Finally, the veterinarian administered an injection of Euthanol, a heart-stopping barbiturate. Bill was brought down from the perch and his death was confirmed. His body was transported to the coroner’s office for an autopsy, observed by a researcher from University of California, Santa Cruz. She noted that Bill’s skull cavity had an unusual shape for a chimpanzee, and as a community debate started on the propriety of using Bill’s body for research, the zoo’s staff considered its potential for revealing new information about Bill and the population of chimpanzees he was part of as an infant.

His exhibit will be torn down and a memorial to him and Ziggy will replace it. The Sequoia Park Zoo will never have chimpanzees again. “We can’t go back there, to those days when Bill first got here,” said Roletto. Asked how the chimp exhibit fulfilled the zoo’s education goals, Roletto said it “educated us about our shortcomings.”

Bill’s significance might have had more to do with society. People who visited him over the years, and those who say they loved him, had a personal connection that’s difficult to explain. Ziegler thinks it involved eye contact, which Bill pursued, often locking his gaze on individual visitors. And a lot could be read into his stare, because his eyes were remarkably human-like.

“They seemed so perceptive,” said Ziegler. “They didn’t miss anything at all. Even in his last hour -- they didn’t miss anything.”

Daniel Mintz writes for a number of local publications, including the Arcata Eye, the McKinleyville Press and The Independent (Garberville) .

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4