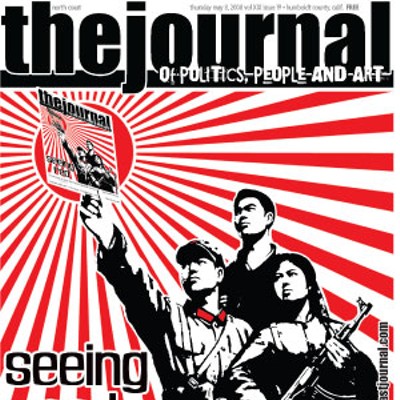

It was the first time I had ever heard the words "dialectical materialism" uttered inside a doublewide trailer. It was also my first glimpse into Humboldt County's small community of communists.

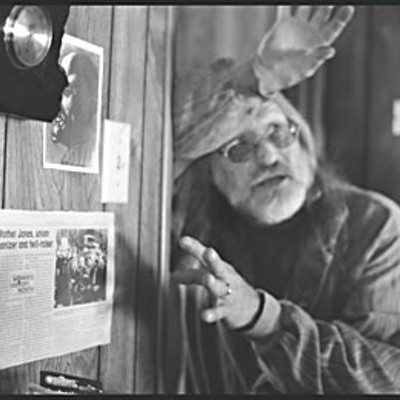

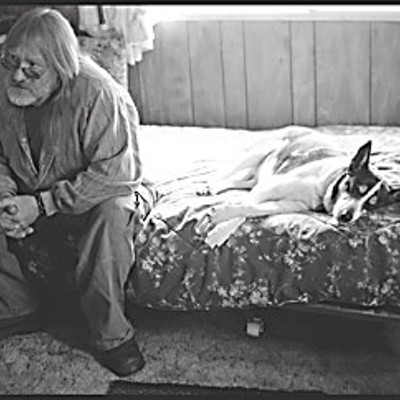

I had come to the right place. Sitting on a twin bed with his dog stretched out beside him in a sunlight-filled room in his McKinleyville home, Michael Langdon, known affectionately by his friends — and comrades — as "Commie Mike," patiently explained the evolution of his personal politics.

He wasn't always a communist, he said. When he was in elementary school he attended a Young Republicans meeting, to the chagrin of his union-organizing father. But it didn't take long for Langdon to realize that mainstream politics wasn't his thing. In the 1970s he joined the Socialist Workers Party, which he describes as more radical than the Communist Party USA, into whose fold he later moved.

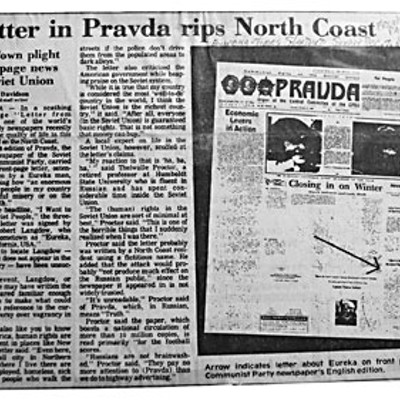

Langdon has been a card-carrying communist since the 1980s and served for the past eight years as chair of the party's local chapter, the Humboldt Communist Alliance. He recently moved into the position of co-chair because he doesn't have a computer, he said, or access to the Internet from his home. The revolution, it would seem, is going to be blogged.

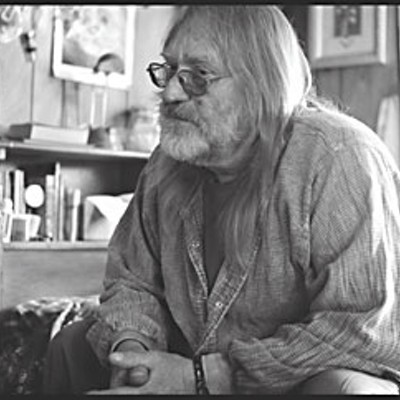

Langdon, 54, short and stocky, looks the part of a radical. His long reddish hair, streaked white, hangs down past his shoulders. He has deeply pockmarked skin and a big nose that pokes out from a full beard. He wears glasses and gesticulates while he speaks about class struggle with a slight lisp.

The walls of his room, which doubles as his office, are covered with an eclectic mix of revolutionaries — Che, Lenin, Uncle Ho and Mao — and tasteful photos of nude women. Langdon's own politics is equally patchwork. A registered Green, he can't seem to recall who the communist candidate for president is this year, but guesses it's Sam Webb, chair of the Communist Party USA. Still, it doesn't really matter since Langdon is backing Barack Obama.

"We support any progressive candidate that will overturn the Bush reign and start coming back to more humanitarian ideals and the end to the war," he said. "The war is a big factor with us. Most of us are all egalitarians and peaceniks."

The "us" refers to the 10-15 registered communists in Humboldt County, according to Langdon's figures. And though that number seems small, he insists that "right now we have an upswing of people interested in the progressive movement, the socialist movement, because the economic situation is getting harsher by the minute." In fact "interest has peaked," he said.

We stepped outside of his room into a dark antechamber. On the wall next to his bedroom door hangs a black and white portrait of Lenin and beside it a newspaper clipping about the origin of May Day or International Workers Day, which is celebrated fervently everywhere else in the world except for the United States. Instead, we celebrate the more anodyne Labor Day with family barbecues to mark the end of summer. As for the real Labor Day, President Eisenhower re-branded it "Loyalty Day" in 1955 because at the time — the Cold War was on — many Americans felt that date was too closely associated with communism.

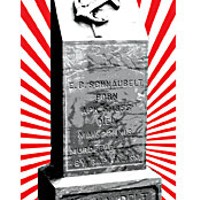

In fact, May Day marks the Haymarket massacre of 1886. On May 1 a nation-wide strike for the eight-hour workday began. On May 4, workers gathered in Haymarket Square in Chicago to protest police violence against workers that had occurred the day before. When the police tried to break up the peaceful protest, a bomb was thrown into their ranks. Among those accused of plotting to commit murder and riot was Rudolph Schnaubelt, who is assumed to have thrown the bomb that day. He fled the country and escaped prosecution. His brother, E.B. Schnaubelt (pronounced snow-belt), would eventually move west to the ocean-side hamlet of Trinidad, where he continued to fight for the dignity and rights of working class men, and died doing so.

Former Arcatan and local literary luminary John Ross used the fiery epitaph on Schnaubelt's grave as a starting point for his memoir, Murdered By Capitalism. That book begins:

Up against the splintery redwood fence at the top of the blazing green jewel box of a cemetery in the tiny fishing port of Trinidad, California, a few dozen miles short of the Oregon line, amid daffodils and daisies and the family plots of dead burghers and loggers, drowned Fisherman and Christianized Indians, a solitary cenotaph wobbles in the Pacific wind like a peg-legged sailor:

*'E.B. Schnaubelt

Born April 5th 1855

Died May 22nd 1913

MURDERED BY CAPTIALISM'*

The solitary cenotaph no longer wobbles, if it ever did. The heavy granite tombstone has a piece of concrete wedged in at the base to keep it erect. And standing beside Schnaubelt's grave a short walk from Trinidad's tiny downtown, one can see the blazing red, white and blue sign advertising the local Chevron station not too far in the distance — an irony that may have the radical Schnaubelt rolling beneath the moist turf.

Someone has balanced two buttons on the anchor emblazoned in bas-relief on the tombstone. One reads "No War," the other "Joyfully Subversive."

According to Ned Simmons, owner of Trinidad Art, an art gallery on the city's main drag, every May 1 there are always red flowers left at the grave. Until the mid-1980s it was the Spinas family — owners of the local gas station — who put the flowers there. Now Simmons and Janis Saunders, whose property borders the cemetery, keep the tradition alive.

Schnaubelt came to the North Coast in 1896 with his wife Tina to homestead — at first on the banks of the Klamath River and later in Trinidad. On the run from his brother's explosive history, but still a socialist, Schnaubelt organized local loggers into a co-op. He set up a shingle mill from scratch on land he'd purchased from The Man — then the Big Lagoon Timber Company. Schnaubelt never got rich, but always had enough to support his wife and two sons, until the depression of 1908 hit. Schnaubelt's business went under and the timber company wanted its land back, but Schnaubelt wouldn't budge. Unfortunately there was no saying "no" to local big timber and in the end Schnaubelt lost everything, including his life. One night, sneaking back into the mill to reclaim his equipment, he was shot by a security guard, Clarence Kelley, who was employed at the time by the Big Lagoon Timber Company. Four shots rang out amidst the still, silent redwoods.

Nationwide, there are around 15,000 registered communists, according to a 2002 New York Daily News profile of Communist Party USA chair Sam Webb. That's down from a peak of 66,000 in 1939. And national figures pretty well mirror local trends. In the early 1930s there were between 30-35 communists in Humboldt County. That number grew to almost 50 towards the end of the decade, according to a 1977 interview with Albert J. "Mickey" Lima, a communist party organizer and a participant in the 1935 lumber strike, conducted by local historian and union man Frank Onstine, who wrote the definitive pamphlet on the incident.

(Earlier, in 1915, Eureka had a socialist moment when three socialists were elected to government office in the same year: Elijah Falk became mayor, Joseph Bredsteen, Fifth District Councilman and W.H. Colwell, Superintendent of Streets.)

When Lima first arrived in Humboldt County, most of the local communists were foreign-born, and many of them were Finnish. They were known as the "Red Finns," having arrived in the States between 1905 and 1917 to escape Czarist Russia. In his book, Onstine explains that the Finns "formed the backbone of Eureka's radical political movement in the thirties." And of the three pickets slain in the 1935 strike, which had started back in May of that year and culminated violently at the Holmes-Eureka mill on Highway 101 on June 21, all were Finns.

Lawyers for the International Labor Defense arrived in Eureka to defend the picketers in the trial following the incident. One member of the lawyers' entourage described the scene at a roadblock on Highway 101 just outside of Scotia on the drive up to Eureka from San Francisco:

The red scare has been raised. The newspapers in Eureka and elsewhere shriek in flaming headline that red sympathizers by the thousands are marching on the town, from the North and the South. The red army is on the way. Sheriffs mobilize; vigilantes arm, the National Guard stands by.

'They shall not pass!' is the slogan.

But we don't look like reds, at least not the conception of reds held by these pickets of the employees. They see no sign of Stalin's heavy black mustache. Not a single bomb in sight. Not a knife held between gleaming teeth. These people can't be reds. They look too respectable. They wave us on. Not a word have they spoken. But guns bulging from their hips and pick handles in hands speak louder than words.

"From the '40s on, the [communists] were pretty well blackballed," Onstine said recently from his home in Blue Lake. Starting in the 1940s, and still in effect when he arrived in Humboldt in the 1960s, lumber and sawmill workers had to swear they weren't members of the communist party before they could get a job. He even remembers an incident in 1967 when Georgia Pacific LLC, which operated two saw mills and a pulp mill in the area, asked the dean of Humboldt State College for a list of those students who were members of the radical left wing organization Students for a Democratic Society. The dean obliged GP by writing up a list of all of the college's left wing students.

Things must have changed after that, because in 1977, a younger Michael Langdon relocated to Humboldt County "for the love of nature," he said, and the progressive spirit of the place.

Langdon folded one leg under the other and — sitting in a half lotus position — explained that there are a lot more communists in Humboldt than the dozen and a half who are "out of the closet," as he puts it. "A lot of people fear what they don't understand," he said. Communism is still a dirty word, but less so, Langdon believes, than it used to be.

He's particularly hopeful that the Internet will provide young people with freer and easier access to information. "There's nothing wrong with ignorance," he said. "There's a lot wrong with misinformation and stupidity."

After World War II fear of communism in the United States was palpable. There were the McCarthy Hearings, the idea that Bolsheviks were hiding in the bathroom and the notion that communists were "going to enslave you instead of bringing you freedom," Langdon said.

For most people those ideas came tumbling down with the Berlin Wall and the end to the Cold War. But some, like members of the John Birch Society, perceive communism as a real threat. They still don't buy the description of McCarthyism as a witch hunt. In fact, they laud McCarthy's efforts to expose communist spies on American soil, and believe McCarthy was unfairly judged by history.

When Gene Owens, head of the local chapter of the John Birch Society, sat down with me recently, the first thing he did was take out a small copy of the Constitution — something he says he almost always carries with him — and read Article IV, Section IV aloud to me. It describes the U.S. government as a republic, a central tenet of John Birchers, who are devoted to restoring constitutional limitations on government. Members of the JBS also believe that a free market system is the best economic model available and that people should be governed by laws rather than men.

"If you were to go play poker at the casino, would you like to play it according to the rules of poker?" Owens asked, "or would you like to play it according to the rules of the majority? Right away you go, 'Well the rules of poker.' And that's what our Constitution is, it's the rule book. And the John Birch Society speaks for the Constitution."

Owens, a meticulously well-kempt older man who speaks quickly and passionately, with a slight tremble in his voice, is worried about being misunderstood by the public. He felt uncomfortable divulging the exact number of JBS members in Humboldt County, but did say that their numbers are "growing."

The specter of communism is growing too. Owens gave me a sheet paper with the 10 planks of communism as laid out in the Communist Manifesto written on it. "Most of those planks are already in place," he said. In short, America is already communist, which means, government control is almost complete.

But Owens' understanding of communism is a far cry from what Michael Langdon hopes the revolution will bring. Owens seems stuck in Cold War dichotomies of good versus evil, a notion of communism as an authoritarian form of government devoid of individual freedoms.

Langdon's hope for the future sounds quite moderate by comparison. "The ultimate goal would be a parliamentarian form of government with a prime minister," he said. "A government that's representative of the people. That all people in the representative government have to hold regular jobs outside of being professional politicians. A government which is answerable to the majority of the people and protectorate of their welfare."

John Meyer, chair of the political science department at Humboldt State University, is teaching a class on radical political thought this semester. His students begin by reading various writings of Karl Marx and Fredrick Nietzsche, then they get "a quick tour" of 20th century radical theorists from Lenin to Bell Hooks.

Meyer has noticed a change in radical politics among students over the years. "What gets viewed as radical politics has splintered and divided in many different directions," he said from his office recently, "so college students today are much more likely to view themselves as radical environmentalists, or radical feminists, or anti-globalization activists ... than they are to identify with something like communism per se."

He pointed out that the word radical means "getting to the root." Thus radical politics are about getting to the root of social problems. With fewer students self-identifying as communists, Meyer says "that reflects the dying of a certain dream that there was a particular sort of intellectual tradition that would unlock all the other issues."

Meyer seemed intrigued to learn that there were more than a dozen card-carrying communists in Humboldt County. But he thinks it's curious rather than prophetic. In a follow-up e-mail to our conversation he wrote, "I don't honestly believe there are any realistic prospects for Communist Party organizing in this country today, I do think that analysts and thinkers who are informed by the Marxist tradition have and can illuminate our understanding of the challenges and problems of contemporary capitalist society."

And he's hopeful that radical activism's turn away from monolithic idea's like communism and socialism towards the "particular challenges of globalization, democratic participation, gender roles, racial conflict and environmental problems allows radical activists to connect with issues that a great many other people that don't think of themselves as radicals are also greatly concerned with."

Michael Langdon mentioned Shane Brinton's name wistfully to me when I asked how many young people are members of the Party. The 21-year-old is the youngest person ever to sit on the Northern Humboldt Union High School District (NHUHSD) School Board. He was also once a member of the Young Communist League. Not anymore.

Before I left, Langdon handed me a 2004 copy of Dynamic,the magazine of the Young Communist League. At the time, Brinton still served on the editorial committee and a fiery anti-war speech he'd delivered at a peace demonstration in Eureka earlier that year is featured in the issue. Except for in one paragraph when he rails against corporate America, urging workers to rise up against their bosses saying, "It is [the CEO's] employees, the rank and file workers, who actually produce the products and provide services that the CEO profits from," the speech seems to fall more into one of Meyer's categories of radically anti-war rather than radically communist.

Perhaps that explains why Brinton has since moved on to the Democratic Party. Still, Langdon spoke of the young man with hope. Regardless of his change of party affiliation, Langdon seemed to imply that Brinton's strong principles remain unwavering. (Brinton declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Langdon believes that change is important, that clinging to old, outdated ideas won't do the party any good. "We still have our same basic fundamental tenets of the Party," he said, "but we change, we see what's evolving and what's needed."

Langdon, who's on disability, does volunteer advocacy work for seniors and the poor. He describes himself as an "on the ground communist, a bee in the hive of progression." Which sometimes causes for minor conflicts in the Party hierarchy. He doesn't just blindly toe the party line, he "gets out there and tries to walk the walk."

When he talks to people, he often identifies himself as a communist. Still, he points out that "communism is just one facet of life." Often he doesn't carry his red membership card with him, just in case he gets pulled over. "There's still the fear of ignorance out there," he said.

"I carry literature," he said. "I carry the People's Weekly World,which is the organ of the Party. I give them a few handouts and I just tell them that we're out here to help the immigrants, the homeless, hungry — equality, gender equality, end to war. I present what I believe. There's no hidden agenda there."

Langdon defines communism as being "all-inclusive." "It means community," he said. "It means for the common good." Later he added, "A word that could be flipped with communism is egalitarianism."

Langdon admits that there are some contradictions that pop up in every day life when it comes to balancing his communist politics with the decidedly capitalist world outside of his bedroom. One day, for example, he went into Eureka to buy a copy of Mao's selected works and paid for the volume with his debit card.

"The guy who was working there ... took my debit card and he says, 'Ahhh, you're the Michael.' And I go, 'Yes, I am the Michael.' He says, 'How's it feel to pay with a credit card?' And I said, 'Come on, give me a break.' And we sat and talked for a minute and I walked out with the selected writings of Mao."

Langdon is a pragmatist. "You have to work within the society you're in," he explained. "I don't care whether you're a communist, a Democrat or a Republican."

And he points to China as a perfect example of communism adapting to survive. "China is a great example of revolutionary economic communism," he said. "They are doing the very thing to advance themselves in the world. They couldn't battle the sea swell that was coming toward them so they decided — and this is the Chinese nature — to use the tool that's being used against them and turn the tool back on the adversary." Others would argue that China is only communist in name.

In the middle of our conversation the phone rang. It was Langdon's son, a master gardener. He wanted to borrow a lawnmower. "Everything of yours is mine," his father said. "Is your son a communist, too?" I asked when he had hung up. No, he lamented. Turns out he trims hedges for Rob Arkley, a member, Langdon said half-jokingly, of the local "ruling oligarchy."

Not far from the cemetery in Trinidad where E.B. Schnaubelt is buried is the home of Simon Green. Green taught Russian history at HSU for over thirty years before retiring in 2007. Recently, he and I talked about communism, Karl Marx, European history and the Soviet Union.

Green is a stout man with a disheveled professorial air. Ensconced in a well-worn leather chair, with a view of the ocean from the window behind him, he said, "One of the great tragedies of the 20th century was the failure of the revolution in Russia, and it definitely failed. And I think that people have identified Marx and Marxist systems so closely with that revolution that they see that that's the end of it. Of course actually communism in the Soviet Union had very little to do with Marx and his views, but that's the way we interpret it."

Green first got interested in studying Russia during the 1950s. He described himself then as "a product of the Cold War." Russia was the "great rival" that needed to be understood in order to be defeated. Looking back, Green says that "Our fear of Russia was fundamentally wrong and our understanding of Marxism was zero."

Communism, socialism, Marxism: "All those words are misused and abused by people," he said.

"Communism itself was one of a series of reactions to modern capitalism," he explained. "Marxism was in the end the most potent of all the reactions. Fundamentally what it claimed was that the economic relations between people were fundamental to our lives and our existence. And that fundamentally what had happened in capitalism ... was that exploitation was the key and that those that controlled the means of production ... were the ones who were exploiting those who actually did the labor."

But Marx assumed that communism would take root in the most industrialized countries, where the workers had it worst off, like England. Instead there were revolutions in China, Cuba and Russia. "Marx," Green concluded, "guessed wrong."

As for the reason why America's fear of communism was so strong by comparison to other European countries, Green can't say for sure. "The reaction of this country in the '20s by the government towards communism was way greater than any threat," he said. "And if you believed that communism was a threat you would have expected that in the European countries, where there was a lot more agitation, that the governments would have taken it as seriously — but we took it very seriously."

John Meyer suggested an idea made popular by 20th century liberal political scientist Louis Hartz. "Because the United States never had a tradition of feudalism in which there were clearly delineated classes in which people were born into," Meyer said, "Americans typically imagined themselves as classless and therefore appeals based on your position in the working class didn't tend to connect with people in this country and didn't tend to be successful."

Green didn't presume to know any details about the present state of communism in Humboldt County, although he did suggest something inherently problematic about trying to take a litmus test of Humboldt's communist community by merely looking for Communist Party members.

"One of the problems you have to face," he said "is that ... there are so many who broke off [from the Communist Party] and became Shachtmanites or Trotskyites and Trotskyists — who disliked each other."

Like Meyer, he interprets the fracturing of the Communist Party as a sign that it was "completely frustrated with virtually no possible way of affecting any kind of change."

"So you talk about the Communist Party here," he said, "maybe there is a Trostkyist Party here, I don't know. A guy who came up to me was a Revolutionary Communist — he was a Maoist! ... There may be one or two of each variety around."

Upon leaving Michael Langdon's doublewide, I noticed a Chinese Yin Yang symbol painted on the front door. Just moments before, Langdon had told me of his deep distrust of organized religion: "More people have been killed, suffered and tortured," he said, "in the name of religion than any natural disaster, any force in the universe." Still, he admitted that he was spiritual.

The communism Langdon ascribes to seems — like the symbol on his door — to embrace contradiction. In a changing world, communists like Langdon hope the revolution will bring a parliamentarian form of government; they are backing Barack Obama for president; and they are willing to laugh about their bankcards. Purists might decry all of this as blasphemy. Langdon would probably invoke that favorite word of his, "dialectical materialism," and emphasize it with a staccato gesture of his hand: "... all things progress and evolve through conflict and contradiction," he would say. Commie Mike is still putting his faith in Marx, but there's a certain local flavor about his willingness to make room for dissenting voices — and maybe it says something profound about where communism in Humboldt County is headed.

Comments