- Yassine Mrabet

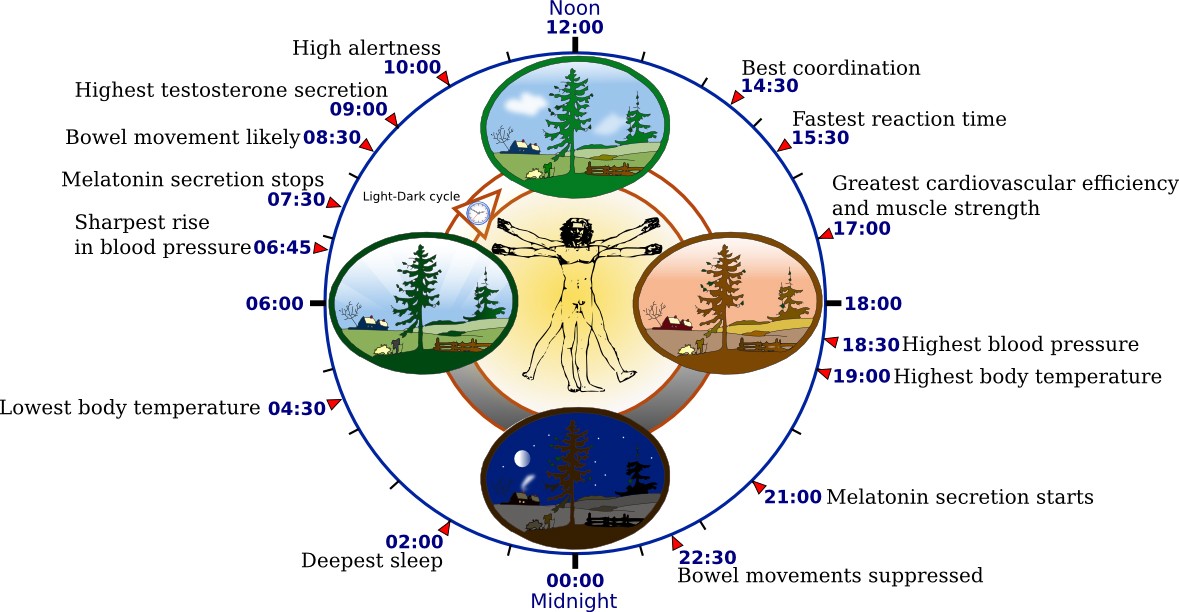

- Contemporary human biological clock, as modulated by artificial light, according to data in The Body Clock Guide to Better Health.

What do you call a habit of regularly waking up at 1 a.m. and not getting back to sleep until 3? Sleep disorder, perhaps? Not if you happen to be Roger Ekirch, professor of history at Virginia Tech and author of At Day's Close: Night in Times Past. His term for such behavior? Normal.

After decades of studying letters, memoirs and diaries from around 1500 to 1750, Ekirch believes that mankind's "natural" sleep pattern is this: go to bed at nightfall for your first sleep; wake a few hours later for a two hour watch, during which time you might pray, talk or make love; followed by your second sleep until dawn. Evidence for this historical sleep-wake-sleep routine goes back to the Greek and Latin writings of Homer, Livy and Virgil, while contemporary anthropologists find the pattern in many rural parts of the world. In central Nigeria, for instance, the Tiv villagers -- who routinely use the phrases first-sleep and second-sleep -- wake during the night "when they will and talk with anyone else awake in the hut," according to one researcher. And when volunteers at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda were deprived of artificial light for several weeks, their bodies reverted to the same sleep-wake-sleep schedule.

According to Ekirch, what we now call "a good night's sleep" -- six to eight hours of continuous sleep -- is an aberration, our body's response to artificial light. While our ancestors normally went to bed soon after sunset, most of us are up for several more hours, thereby depriving ourselves of the natural middle-of-the-night waking period. According to Harvard chrono-biologist Charles Czeisler, "Every time we turn on a light, we are inadvertently taking a drug that affects how we sleep."

Ekirch turned up one particularly tantalizing tidbit in his research: a near-unanimous experience of serenity and contentment during the watch period. People prayed, meditated on dreams, smoked tobacco, talked, loved. If they could afford candles, they read or wrote. "At no other time during the day or night were distractions so few and privacy so great," writes Ekirch. He quotes Nathaniel Hawthorne: "You have found an intermediate space, where the business of life does not intrude." More prosaically, the NIMH researchers noted raised levels of prolactin in volunteers' blood during their 'tween sleep periods. Prolactin is the nurturing, calming hormone responsible for milk production after childbirth, a sort of anti-dopamine -- it's what keeps chickens happily brooding on eggs for days at a time.

Most of documented history -- the battles and treaties and betrayals -- took place in daytime. Now that we are learning a little about the history of the night, we are finding that our ancestors might consider our ideal of uninterrupted sleep to be an abnormal deficiency.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) gets most of his information about sleep from Neil Gaiman's Sandman.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2