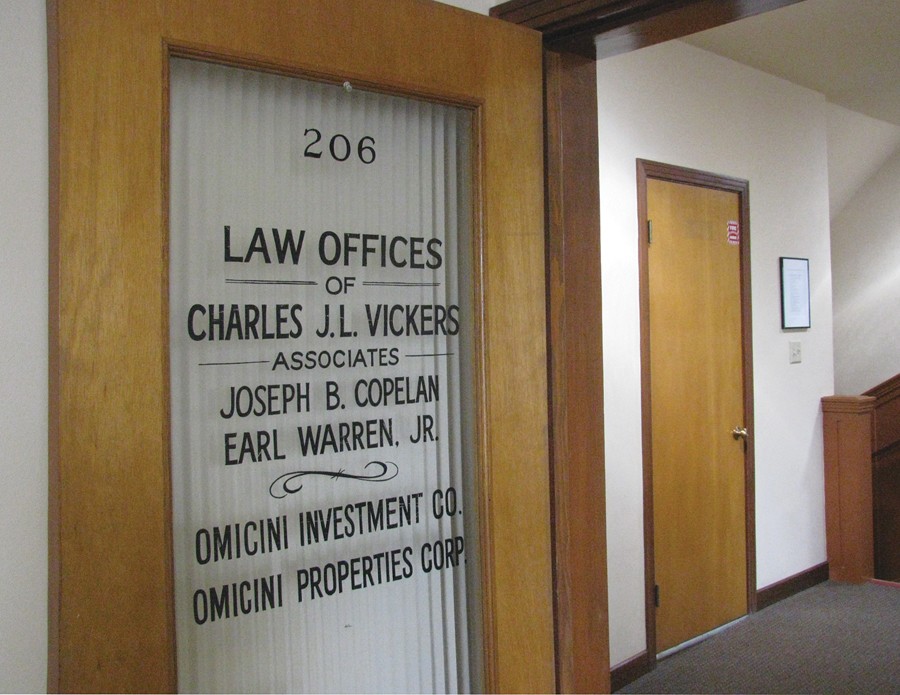

- photo by Holly Harvey

- When Architect Jack Freeman remodeled the upstairs of the Omicini Building—310 F St., Eureka—for the North Coast Journal offices, he left the original mahogany doors and lettering in place.

When the Journal moved to its new offices in the Omicini Building at Third and F in Eureka, more than few staff eyebrows were raised by the sign on the door of Room 206. There, on a frosted glass window straight out of The Maltese Falcon, was the name Earl Warren Jr.:

Could this be the son of the Earl Warren, arguably the most famous Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court?

The short answer, it turns out, is yes. The longer answer comprises the rest of this story.

It starts in December 1964 when Pete Omicini -- who not only owned the Omicini Building and the adjacent Greyhound Hotel, but also Pete’s Market and Pete’s Cave in Bucksport -- left the Cave after having a couple of drinks. Nearby, at the intersection of Broadway and McCullens, Omicini noticed a CHP car with two officers inside. He approached the vehicle and, placing his hands on the passenger-side door of the car, allegedly berated the officers. They responded by arresting Omicini, charging him with public drunkenness and interfering with an officer in the line of duty.

In May of 1965 Omicini’s case came to trial. It got off to a rocky start when only eight jurors were seated from the original venire of 40 local citizens. Not to be deterred, Judge Charles M. Thomas ordered district marshals out onto the streets of Eureka, where they commandeered an additional 15 prospective jurors to fill the panel. The following week the improvised jury found Omicini not guilty of public drunkenness but convicted him of interfering with a police officer. The court fined Omicini the maximum, $1,000, and also handed down a 60-day suspended jail sentence and a year’s probation. Omicini’s trial attorneys, Alvin Cibula of Shasta County and Jeremiah “Jerry” Scott Jr. of Eureka, appealed the decision. In October 1965, a three-judge county appellate court panel rejected the appeal. The judges emphasized that Omicini had “hung on the patrol car in which officers were seated and refused to permit them to proceed.”

Next was an appeal to the U. S. District Court of Appeals in San Francisco, but it also upheld the conviction. Then came a petition to the California State Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case. By now, Omicini was 0 for 4, but he was still swinging. He wanted his attorneys to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In April 1966, Omicini contacted Scott, his Eureka attorney, and asked for a meeting. It was held in Scott’s office, and Omicini came with two new attorneys, Charles L. Vickers of Los Angeles and Earl Warren Jr., who practiced law in Sacramento. Vickers took the floor, telling the group that he was going to join the appeal and that he had asked Warren to also sign on. He then boasted that with Warren Jr. on the team they would have no trouble gaining a favorable decision from the Supreme Court, over which Warren Sr. presided.

Scott and Warren Jr. were silent during the meeting. Scott, stunned by Vickers’s claim that such a preposterous scheme would work, sat at his desk for two or three minutes. Then Warren Jr. returned. He was visibly upset and apologized to Scott, informing him that he had come to the meeting without knowing what Vickers had planned. Warren Jr. indicated that he would certainly not be involved in the case.

A couple of weeks later Scott petitioned the court to withdraw as Omicini’s attorney. Vickers attended the resultant court hearing, where, according to Scott, Vickers appeared to fall asleep. Scott’s petition to withdraw was approved, leaving Vickers as Omicini’s sole attorney. A few weeks later, Vickers died in Los Angeles.

Even though Omicini embraced Vickers’ impossible plan for the Supreme Court appeal, he probably would have reconsidered his choice of counsel if he had seen his new attorney’s State Bar rap sheet. By 1942, Vickers had been suspended from the bar based on two proceedings covering four different complaints. If that was not enough, he then engaged in a series of events straight from the most sordid “B” movie. First, Vickers began the process to obtain a quickie Mexican divorce from his wife, Gloria. He did this while traveling with an “acquaintance,” Olive Kirk. Two days later, claiming that he was now a single man, Vickers married Kirk. The couple lived together for the next few months as husband and wife. Kirk became ill and died in Los Angeles in July 1943.

Within days, Vickers, claiming to be Kirk’s husband, petitioned for standing to allow him to administer Kirk’s estate. He claimed this was necessary partly because he was without funds and needed money for Kirk’s funeral. Vickers’ initial petition was granted, but before he could gain further administrative status, Kirk’s mother intervened. She indicated that Vickers had “made no move to have body taken care of” and that she “was forced to pay the expenses of funeral services and interment.” At a hearing, Vickers had his status revoked and Kirk’s mother was appointed administratrix of her daughter’s estate.

The State Bar investigated Vickers’ shenanigans. They learned that in addition to failing to properly administer Kirk’s estate, Vickers had failed to obtain either a legal divorce or a legal new marriage and that he had falsely claimed otherwise when he petitioned for administrator status. Because of these activities the State Bar investigating committee decided that Vickers should be disbarred. He appealed the decision and the court, in Vickers v. State Bar [32 Cal. 2nd 247], granted a modification: Vickers was to “be suspended from the practice of law for a period of three years.”

By then it was 1948, which left plenty of time for Vickers to serve his suspension and go back in action as an attorney of dubious methods. By 1966 he had refined his technique to the point whereby he not only convinced Omicini to retain him in a sure-to-be-lost cause, but he somehow also succeeded in having his client set up an office for him in the Omicini Building. Thus the names on the frosted glass, which besides those of Vickers and Warren Jr., also included that of Warren’s law partner, Joseph B. Copelan. Warren had not asked for and never used the office. In the late 1960s he was appointed judge in the Sacramento Municipal Court by then Gov. Ronald Reagan.

The Journal has kept the door to Room 206 as it was in 1966, a memento of the most famous Eureka law firm that never existed.

Comments (3)

Showing 1-3 of 3