The announcement just over a month ago from Humboldt State University President Rollin Richmond was confusing and alarming: An unidentified faculty member had resigned in fear after finding a note expressing racial hatred. Beyond that, the contents of the note were not released, nor was the identity of the faculty member, who had requested discretion. Richmond simply called the incident "a hateful and cowardly act," and on behalf of the university he pledged an "absolute and unequivocal refusal to tolerate this kind of behavior."

That wasn't enough explanation for most of us. The event just didn't jibe with our vision of the university as an open-minded intellectual harbor where prejudice is banished to the world beyond the stucco, mission-style sentry gates. We wondered who would write such a nasty message. Even more confusing, though, was the faculty member's reaction. Why quit over a simple note, one that, according to reports, didn't specifically threaten or even name anyone? There must be more to the story.

When the Times-Standard reported what little was known, online commenters went so far as to suggest that the faculty member (a female tenure-track professor, as it turned out) probably wrote the thing herself.

It's comforting to dismiss the event as merely an unfortunate but probably isolated prank that prompted an absurd overreaction. And since few other details have emerged, that seems as likely an explanation as any. That is, until you start to look closer at the complex dynamics of race and ethnicity on the HSU campus. People have been looking closer, and what they've discovered is troubling.

In 2003, a team of administrators, faculty and staff assembled by President Richmond developed a Diversity Action Plan designed to increase the ethnic diversity of the campus community and curriculum. As part of their research, the committee examined a wide range of diversity-related indicators, from the ethnic makeup of the student, faculty and staff populations to the performance and persistence rates for each group, as well as their personal feedback.

Last spring, HSU Provost Robert Snyder requested annual reports from this group, known on campus as the Diversity Plan Action Council. The first of these reports was released in August. In the introduction, Snyder identifies "the twin goals of diversity and inclusion." What the report reveals, according to authors Radha Webley and Patty Yancey, is exactly the opposite: "Section by section, these pages tell a story of inequity and exclusion, a story where Students of Color on our campus feel isolated and uncomfortable...and marginalized academically."

In Humboldt County -- inordinately opinionated, proudly individualistic, disproportionately white -- the mere mention of race can raise hackles. Then again, we may be no different in that regard than anywhere else. Despite (or is it because of?) the election of Barack Obama, the subject remains exceedingly touchy, with accusations of racism, reverse discrimination and "playing the race card" regularly streaking through the national dialog. College campuses, far from immune to these allegations, are frequently characterized as indoctrination factories where liberal professors implant their skewed ideologies on vulnerable young minds, or, conversely, as bastions of critical thinking where ignorance, prejudice and a legacy of institutional oppression get systematically and righteously torn apart.

The diversity report provides context for a slew of recent events that, viewed together, suggest HSU may be just as vexed and anxious about race as the rest of us. A professor was intimidated into leaving HSU, and there is indeed more to the story. But to see it, you have to look past the protagonists to their surroundings.

^^^^^

Among the eight goals articulated in HSU's Diversity Action Plan are calls to increase the diversity of faculty, staff, administrators and students to reflect the respective job pools as well as California's demographics. Like other northern California schools, including Chico and Sonoma State, HSU has struggled to attain these objectives. While some progress has been made at HSU over the past five years, the campus remains disproportionately white.

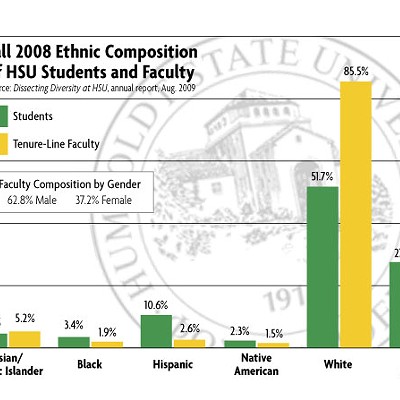

As of last fall, a whopping 85.5 percent of the school's 269 tenure-line faculty members identified themselves as white. Just over 11 percent identified as persons of color (3.3 percent were unknown). Compare this to the nearly 25 percent persons of color in the applicant pool and 29 percent of tenure-line faculty across the CSU system. Statewide, persons of color make up 57 percent of the total population.

The student population looks somewhat less monochromatic, though it's impossible to calculate exact figures since more than one in four students marked their ethnicity as "other" or "decline to state." Research suggests such students tend to be predominantly white, but leaving them out of the calculations altogether results in a student body that's 71.3 percent white, 14.5 percent Hispanic, 6.3 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.8 percent black and 3.1 percent Native American.

Not only are minorities under-represented at HSU, they tend to have a harder go of it once they arrive. Likely not coincidentally (recall the anonymous hate mail recipient), faculty of color leave in much larger proportions than their white counterparts. From the 1999/2000 academic year through 2007/2008, they resigned at two and a half times the rate of white faculty.

Theories on this trend abound. Sociology Professor Jennifer Eichstedt, who serves as co-chair of the university's Diversity Planning Action Council, says the explanation is probably not overt racism but a more passive phenomenon known as the social reproduction of power. "In hiring practices, there are subtle ways that administrations reproduce themselves," she explained. "[Minority] folks are removed from the [applicant] pool, and it's never because people don't have the best intentions to bring in a person of color. But it's little unintentional stuff like, 'I'm not sure they'll fit in here.' What they're really saying is, 'Who do I want to have a beer with?' and that's usually somebody who looks like me, sounds like me and does what I like to do."

Even when minorities are hired, Eichstedt said, they're often excluded socially and subtly (or not-so-subtly) made to feel unwelcome. Their eventual departure becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy.

While not quite so dramatic, similar trends show up in student persistence rates. From 2000 through 2007, three-quarters of all white freshmen continued on to a second year at HSU while, among black students, the rate was 71 percent and, among Native Americans, 66 percent. From second to third year, persistence rates dropped to 61 percent among whites, 55 percent among blacks and 52 percent among Native Americans. Students who graduated in a six-year period: whites, 47 percent; blacks, 32 percent; Native Americans, 24 percent.

The results of the diversity report didn't surprise the two women who comprise HSU's Office of Diversity and Inclusion -- Associate Director Radha Webley and Faculty Director Patty Yancey. Almost everyone else, however, was shocked. "And because of that shock, it's stimulated a lot of great conversations," Webley said. During an interview at their office last week, Webley and Yancey emphasized the power of quantified data as a tool for change.

"It's about connecting the dots," Yancey said. Viewed separately, individual events can be explained away. Broad trends are more difficult to dismiss. Professors and department heads see the data, Webley said, "and they go, 'Gulp. You mean students of color failed that class at three times the rate of white students?'" Attitudes on campus have already changed as a result, she said. "Departments have invited us to come talk to them, as has administration. There's lots of support for moving forward."

^^^^^

Not everyone has embraced HSU's diversity efforts with open arms, though. On Oct. 13, HSU's student newspaper, The Lumberjack, published an opinion piece by a woman named Jeanne Brown, who criticized HSU and the public education system at large. "[I]f you look at many of the textbooks and listen to what is said in the classroom, you will see that diversity means bashing everything European," Brown wrote. She called for recognition of European American Heritage month, reasoning that, "If other ethnicities are being encouraged to celebrate their ancestral heritage and heroes, then white students have the same right."

Attempting, in her view, to correct the historical record, Brown called the Civil War "Lincoln's illegal war of aggression" against the sovereign Confederate States of America. Among her other claims: The Emancipation Proclamation was nothing but "empty rhetoric"; no Northerner fought to abolish slavery while no Southerner fought to uphold that right; the Revolutionary War was fought largely because the King of England was pushing slavery on a resistant America; and, going further back, the first inhabitants of North America were, in fact, "highly moral and civilized" white people who gave the arts and sciences to the American Indians.

"We did have a discussion about the column initially," said journalism Junior and Lumberjack Editor-in-Chief Sara Wilmot. "The editorial board determined [Brown] was not making any threats; there were no references to illegal activity. The paper is a community forum, and she's a community member. So we printed it."

The following week, The Lumberjack published two letters in response to the piece, both of them critical but respectful in tone, and Lumberjack staff figured that was that. Soon, however, people began noticing the online comments that had been accumulating below Brown's opinion piece. A majority of posters supported Brown's assertions and had added more of their own, using increasingly offensive terms under the guise of anonymity. One comment (posted under the name Jeanne) defended the Ku Klux Klan. Another claimed whites have seen the nation devolve into "a third-world cesspool." Yet another decried "Jews who wage their war against the White race by promoting homosexuality and filth in our media."

Lumberjack staff eventually removed all comments from the page and last week published their own editorial addressing the controversy and articulating a comment policy. Wilmot said the incident shows that race is still an issue on campus. "A lot of people have been trying to sweep it under the rug," she said. "Just the fact that [people] were posting anonymously shows they're not willing to discuss it openly."

But Brown and the secretive posters aren't the only ones who have questioned the value of diversity and the methods being used in its pursuit. A common complaint among students and outside critics alike is that the forces of political correctness have pushed the curriculum pendulum too far, sacrificing the benchmarks of quality education in favor of inferior works and ideas -- a pernicious example of affirmative action.

"When students say that, I say, 'Let's be empirical -- let's look at [the courses] you've actually taken," said Eichstedt, who's been accused, she said, of harboring an anti-white agenda. Invariably, such student perceptions are inaccurate, Eichstedt said, and she pointed to American housing patterns by way of analogy. "Whites move out of an area when the percentage of African Americans [reaches] 10 percent," she said. "They perceive it's being 'taken over by blacks.' ... What I'm trying to do is critique whiteness as a category. It was a category that was explicitly made up to be about property ownership and about access to social, political and economic rights."

As for the value of diversity itself, HSU's Diversity Action Plan cites studies conducted by the American Council on Education and the American Association of University Professors, which found that a diverse campus and curriculum benefits all students, not just minorities, "by challenging stereotypes, broadening students' perspectives, and sharpening critical thinking skills."

^^^^

More important than white students' inaccurate perceptions are minority students' experiences at HSU, and the diversity report's graphs and figures tell only part of that story. The report also summarizes student feedback, in which black and Native American students in particular reported feeling less supported academically, less sense of community and less connection to HSU as an institution. Students interviewed on campus last week, however, painted a more complex picture.

Ying Xu and Jing Tang, both from China, said discrimination does exist on campus while Andrea Lee, a sophomore music major from Singapore, and Bo Sheng, a sophomore business major from China, said they had not experienced any prejudice. Edwin Vazquez, a gay Latino student who grew up in Mexico and Orange County, said he was apprehensive when he first arrived on campus but that finding the MultiCultural Center gave him confidence to express himself. Standing behind a rainbow-colored table advertising events for this week's Campus Dialogue on Race, Vazquez said the MCC is "a good resource for everybody, especially minorities because, as you can see, this school is not as diverse as many other schools."

HSU has numerous other clubs and organizations geared toward minority students, including the Black Student Union, Latinos Unidos of HSU and the Asian Pacific American Student Alliance, among others.

Nevertheless, a Native American MCC staff member and HSU alum, who declined to give her name, said she sees bigotry and hatred on campus firsthand. "People come in and tell me about their issues with professors and fellow students," she said. Last semester, she recalled, fliers for cultural graduation ceremonies were defaced with ethnic slurs.

Two separate groups of black students from Los Angeles sitting on the quad last week said that, compared to where they're from, HSU is peaceful. "In L.A. they have black-on-black crimes, Hispanics-on-Hispanics -- they fight against each other," said Edward Walker. "But up here -- ." His friend, Prince Moseley, finished the thought: "It's friendly up here."

"Where we're from, we always had our guard up, and we carried that mentality up here with us," said Barry Davis, another black student from L.A., two days later. "People in [Arcata] are friendly," he said. "My first day walking down K Street, people were just waving at me. 'How are you doing?' It was a culture shock. And I'm looking at them like they're crazy, you know what I'm saying? And they're looking at me like, 'Why's he not waving back?'"

Other students said their experiences off-campus haven't been so welcoming. One recalled being referred to as "colored" while working at the Bayshore Mall. Another had "nigger" repeatedly shouted at him from a pickup truck in Arcata. A Native American woman said she and her friends were ignored at a Fortuna restaurant because they're "brown."

But Walker gave the school high marks for its efforts. "They branch out to different minorities, kids from inner-city schools, and bring them up here," he said. "I live in that experience, and everything up here has been cool for me. ... In L.A., honestly, I feel like I can't do a lot of stuff. I can't wear certain colors out there."

"Your life can get taken," Moseley agreed. "It's that simple. When you get up here you have the freedom to do whatever you want to do, wear what you wanna wear and just be you."

^^^^^

There are countless factors beyond HSU's sphere of influence that likely contribute to the inequality revealed in the diversity report, including socio-economic disparities, cultural differences and what the Diversity Action Plan calls "institutional oppression imbedded within the U.S. and California system of education."

"But at some point," Webley said, "you need to intervene and own that responsibility to actually make a difference. High schools blame middle schools; middle schools blame primary schools; primaries blame kindergarten and preschool, and they blame the family. At some point, if you're concerned about the implications of this long-term for our society and for our economy -- it has lots of workforce implications as well -- at some point you have to say, 'OK, that's my institution's responsibility. I'm going to change that.'"

Webley and Yancey agree that progress is being made. Amid unprecedented budget cuts and ongoing accreditation problems, administrators have followed recommendations from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, the university's accrediting body, and made "inclusive excellence" a guiding principle, Yancey said. Provost Robert Snyder recently created a Cabinet for Institutional Change aimed at making campus-wide transformations, and the Diversity Plan Action Committee is developing an anti-bias rapid-response team to handle the aftermath of events like the hate note incident. This week, HSU is holding its 11th annual Dialogue on Race, called Race in the Age of Obama, which includes lectures, film screenings, book readings and workshops.

It's more than just dialog, in other words. Until fairly recently, diversity efforts at HSU have been more talk than action, Eichstedt said. "The difference has been with [President] Richmond." She credits both the president and the provost with facilitating real changes on campus, though she cautioned that there's still a long way to go, not just at HSU but in the larger community. "No matter how hippy and groovy a place thinks it is, [discrimination] is going on," Eichstedt said. "You have to change the culture." When asked how, she rattled off a list: training, financial and philosophical support, changes to the curriculum and a lot more public dialog. She called such efforts survival work. "If we don't fix the inequalities and the fear, anxieties and distrust, it's one of the things that will destroy us," she said. "I mean that literally."

Comments (23)

Showing 1-23 of 23