The school buildings were falling apart. Old and heavily worn, first in military service for Fort Gaston and then as the campus for the Hoopa Valley Indian Boarding School, they required enormous upkeep. That burden fell on the shoulders of Sherman Norton, a Hupa man hired in 1912 as a carpenter for the federal Indian Service, the workforce of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Norton, a determined man, did the carpentry, but he also patched pipes, rewired the electricity, fixed the school's laundry equipment, and maintained the 44 miles of telephone line strung out over the mountains that connected the Indian Agency with the rest of the world. For all of this, he received the "Indian" wage rate of $45 per month.

For six long years, from 1912 to 1918, Norton wrote to the commissioner of Indian affairs insisting that he be paid $60 per month, the salary that the previous white carpenter had received. The duties he was performing, Norton pointed out, went far beyond his job description. When the government refused him a better salary, Norton stopped doing tasks other than carpentry. This infuriated his supervisor, Superintendent Jesse B. Mortsolf, who labeled him a troublemaker and recommended that the Indian Office transfer him away from Hoopa Valley to another reservation. So Norton quit. He may have found some satisfaction when the Indian Office later had trouble finding someone else to do the job at his salary. Several years later, when Mortsolf transferred out of Hoopa Valley, Norton and his wife, Ella Jarnaghan Norton, began working for the Indian Service again. He became chief of the Indian police force at $720 per year - the same $60 a month he'd originally hoped to receive in 1912. She became the school's laundress, at $760 per year.

Sherman and Ella Norton lived at a time when the federal government was bent on destroying Indian tribes and Native cultures. White officials believed that if Indians did not give up all of their traditions, they were doomed to disappear. The solution, the government argued, was to "kill the Indian in him and save the man" by forcing Native people to abandon their cultures and conform to the white way of life. The federal government chose the Indian Service as its weapon of choice for this attack. The service targeted entire Native communities: It outlawed their religious ceremonies, forbade traditional hunting and fishing practices like the Hupas' annual fish dam, and divided tribally held land into individual homesteads, selling off the remainder to the highest bidder. Perhaps most heartrending, it also rounded up Indian children and forcibly sent them to boarding schools to keep them away from their families and communities.

This raises the question: Why would the Nortons, or any Natives, want to work for a bureaucracy trying to annihilate their culture? What was the attraction of this anti-Indian agency, and why was the pull so strong that in 1912, the year Sherman started as carpenter at Hoopa, almost 30 percent of the Indian Service's 6,000 employees were Native?

The answers lie in letters and memoirs, in government reports and personnel files, in employee logs, diaries and a wealth of records that have begun to paint a new, revealing portrait of the whites and Natives who went to work for this Indian Service. The surprising answer, for many Native peoples, is that they worked for survival -- and for subversion. They became adept at turning the government's own tool against itself, working within the system to ease its harshest effects. As Indian Service employees, they were perfectly positioned to offer a sympathetic ear to a lonely schoolchild, explain complicated government regulations, advocate for friends and relatives who were being mistreated, and keep their families together. These were strategies used not just by the people in Hoopa Valley, but by many around the American West.

The story of their struggles to persevere, and the lasting impacts they made on some white employees, emerged from nearly a decade of research. Their stories are told more extensively in the new book, Federal Fathers & Mothers: A Social History of the United States Indian Service, 1869-1933. They're summarized here because these stories - and the people who lived them -- helped shape the future. The United States government spent long decades and hundreds of millions dollars trying to destroy Native nations and their cultures. In the end it did not succeed. It failed primarily because Indians resisted in many ways: everything from risking arrest for participating in religious ceremonies to continuing to cook their traditional foods for children and grandchildren. The Hupa, especially, resisted by refusing to leave their homeland. It is no accident that tribal member Byron Nelson Jr.'s history of Hoopa Valley is entitled Our Home Forever. In the face of massive and persistent federal efforts to annihilate Indian cultures, what might seem like small or scattered decisions by Native people should be recognized as significant acts of heroism.

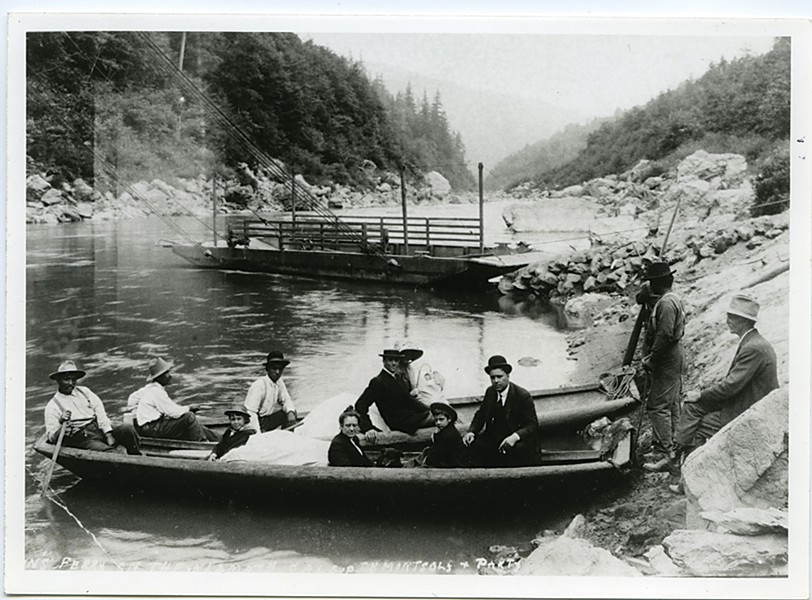

Often, those heroics had the most everyday underpinnings. An Indian Service job was sometimes the best economic option for staying home, rooted in community. Hoopa Valley, far from the cities on the Pacific coast, was typical of the harsh economic choices many Native people faced. Their old ways no longer could feed a family. In their valley, the Hupa peoples' supply of traditional foods, especially salmon and acorns, had been drastically damaged by the Gold Rush, the salmon canneries at the mouth of the Klamath, and the chopping down of acorn-bearing oak trees. Some wage-paying jobs were available in the lumber camps or in the coastal towns, but that meant leaving Hoopa Valley, the center of the Hupa world. It was an arduous journey over narrow mountain paths on foot, in a bone-shaking wagon, or on the back of a horse or mule, with no options for frequent returns. Most jobs available to Indians would not have offered much time off to take the trip home.

At Hoopa, officials reported again and again that tribal members didn't want to leave the valley -- and many Hupa put in requests for jobs at the federal Indian school. Norton knew he could make a better living working off the reservation, but staying at home was more important. His letters to the commissioner of Indian affairs reveal that he was afraid that if he went away he would lose his rights as a tribal member, and his wife also refused to leave her home in the valley. By working for the government at Hoopa, they could stay and participate in the tribal ceremonial life. As an employee at the Indian School, Sherman was able to keep an eye on his children. Superintendent Mortsolf constantly complained that Norton was "interfering with the discipline" at the school and causing problems with other employees. Most likely Norton was simply objecting to the harsh treatment of his children. Morstolf also reported that Norton, along with John Carpenter, was serving as "a sort of lawyer and advisor among the Indians." Because they worked for the Indian Office, they may have been in a good position to help their fellow tribal members navigate its bureaucracy.

Like Norton and Carpenter, many other Native employees -- the very people officials thought of as most "civilized" -- quietly resisted the government's plans to destroy their cultures and communities. Although they were legally Indian "wards" without the rights of citizenship, and were dealing with administrators who often described them as children, they defended their interests and argued for their rights. Most important, they continued to attend their ceremonial events. They continued to think of themselves as members of a nation that belonged in Hoopa Valley, in their language, Natinook, "the place where trails return."

Miss Martha E. Chase was 54 years old in 1901 when she rode over the trail to Hoopa Valley to serve as the missionary for the Presbyterian Church. Chase had dedicated her life to the service of Jesus Christ and her church. With her white hair pulled back and topped by small hats and her long dresses that swept the ground, Chase busily pursued her goal of converting the Indians in Hoopa Valley. She was assisted by Nellie McGraw (later Hedgepeth), a younger and less stern woman. After being in Hoopa a short time, both Chase and McGraw were hired by the Indian Service to temporarily fill the positions of teacher and assistant matron when other employees were sick, on vacation, or in the midst of transfers to and from other reservations. Missionary and Indian Service employees overlapped on many reservations because the goals of the federal government and the churches were essentially the same. And yet, like many women in the service, these two would be drawn toward Native cultures, and sometimes, almost despite themselves, would help traditions endure.

Chase and McGraw saw themselves as part of a sisterhood of women, a sentiment shared by many white women in the service. They had taken their positions believing that they were helping Indian women by encouraging them to abandon their cultures. They were tasked with teaching Indian women and girls how to make "white women's bread," sew clothes for themselves and their families, raise their children like whites, and clean and decorate their households in a particular way. They visited Indian women at home and opened their houses as an example of how to live. They taught Sunday School, held services and founded chapters of the Women's Christian Temperance Union and the King's Daughters. They were convinced that unless Native families conformed to these new ways of life, they would die out.

Nellie McGraw kept careful track of their visits and visitors in her diary. On the lighthearted side, school employees came by to gossip, borrow a book, or invite them to a party. Their Hupa guests stopped in to say hello, share a meal, and exchange reservation news. That news was often sorrowful, with illnesses and deaths all too common on reservations where residents were poor and poorly housed. Chase and McGraw would visit the sick, bringing food, offering their services as nurses, and often having an "earnest talk" with them about heaven. Sometimes this was welcome. Sometimes the families refused their help or accused them of making the patient worse. Many times the women arrived to find that an Indian doctor was attending the sick person, using traditional Hupa methods. They bemoaned the persistence of Indian medicine and blamed the ceremonies for aggravating the illness.

When illness led to death, they attended the funerals and were genuinely sorrowful that one of their friends had died. But even then they were judgmental, lamenting the families' decisions to use traditional methods of burial. The women also revealed their ambivalence about stamping out Indian cultures. Nellie McGraw was fascinated by the funeral traditions, confessing to her diary that she strained her neck to catch every detail: mourners who had cut their hair, or a grave full of the deceased's belongings covered with "Indian money," the dentalia shells that held value for the Hupa. She brought her camera, and knowing that people would have been upset by her rude behavior, she waited until most mourners had left before surreptitiously taking photographs.

Chase also had moments of doubt about her right to intrude. One year when the superintendent halted a ceremonial dance, the Indians blamed her and came to her house to protest. The house was full, she remembered, of "sorrowing men and women." Chase took the opportunity to give them a "sermon" about why the dance should not be held, but she had to listen to several sermons from them in return. This experience shook her and she confessed, "It is pitiful to rub a religion from a people that can be so very sincere and earnest as these are...May we make no mistake."

Perhaps in spite of herself, Chase helped Native women preserve aspects of Hupa culture. Often when women like Annie Shoemaker, Sarah Davis, Lena Pratt, Ollie Jackson, or Susie Matilton came to call at Chase's house, they had a specific reason: to sell her a basket or two. Chase bought the baskets from these Native artisans and sold them to white women in San Francisco, San Jose and elsewhere across the country who were eager to have them. For the Indian women, the money from these sales mattered deeply. Basket prices averaged around $5 -- roughly a week's wages for an unskilled laborer for the Indian Service.

Chase bought all the baskets she could and even passed on special requests from buyers for miniature versions or specific colors. She learned how the different kinds of baskets were made and what they were used for, and she shared her knowledge with other white women. In an article for Club Life, the magazine of the California Federation of Women's Clubs, Chase wrote, "The introduction of white man's food and habits has done away with the need of the old store baskets, but the one staple article of Indian ‘grub' is the sahow, made from acorns. This acorn soup requires no less than six widely different baskets, a fine bristle brush, a paddle and a pounding stone or pestle in process of its manufacture from the acorn."

What Chase may not have realized was that the physical act of basket making could not be isolated from the spiritual and cultural aspects of weaving a basket. When a woman wove a piece, she had to know where to find the right plants and materials, she had to choose from among the patterns that held specific meanings, and she had to know which medicine (prayers) to make for basket weaving. So the sales brokered by Chase and other employees undercut the government's drive to eliminate all things Indian, and kept basket making knowledge alive for future generations.

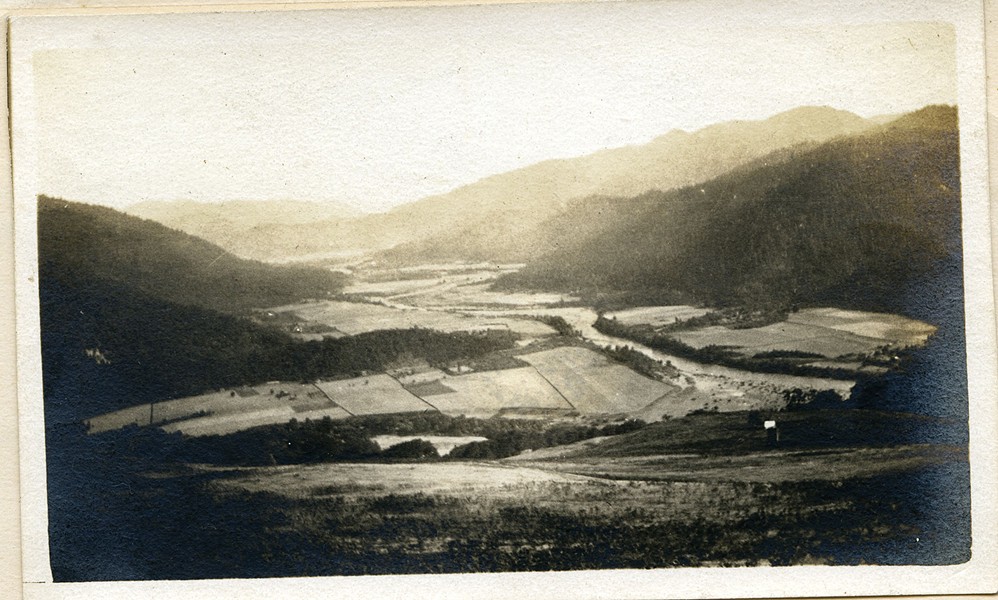

At the heart of Hupa territory is Natinook, which whites renamed Hoopa Valley. The Trinity River flows through the middle of the valley, and before whites arrived in great numbers during the gold rush, the Hupa villages, divided into northern and southern districts, were strung like shell beads along the river. Most of the villages nestled on the eastern bank to catch the sun that warmed the smooth cedar plank roofs and walls of the xontas, the main family dwellings where women and children slept, and the roofs of the subterranean taikúw, or sweathouses, used exclusively by the men.

By the end of the 19th century, the valley had changed. Some Hupa still lived in xontas, but most resided in frame houses. The beauty of the spot still shimmered, parklike, in accounts of new Indian Service employees and others arriving for the first time in Hoopa after a long journey. One visitor wrote: "On descending the mountain the traveler looks upon a fertile valley several miles long profusely dotted with grain fields, vegetable gardens, clusters of trees and horses.... A portion of the river connects with a mill, another supplies the fish hatchery, reservation fountain and grounds. From a distance the whole valley looks very much like a cultivated park." This view emphasized the vision the Indian Service had for the future of Hoopa Valley. It focused on the new buildings, the agriculture, and the economic possibilities of the valley. The Hupa saw it through different eyes. Their world had been violently disrupted first by a flood of voracious miners, then the United States Army, and finally, the Indian Service, which established a boarding school in the valley in 1893.

The changes that whites brought to Hupa territory happened almost within a single lifetime. Many Hupa had been young men and women when whites arrived in large numbers. They saw the United States take over 80 percent of Hupa territory. They watched new buildings go up, plows break the ground, and axes bite into oak trees. They witnessed their tribe's population shrink from almost 1,000 to just over 400 people as a result of violence and disease. Despite these wrenching experiences, the Hupa people refused to surrender their identity as Natinook-wa, the people of Natinook. They clung to this knowledge even as their land became a cultural mishmash. To get rid of "troublemakers," as Superintendent Mortsolf had tried to do with Norton, the Indian service transferred them among reservations. Native peoples from around a dozen states, as far away as New York and as climatically foreign as New Mexico, came to live there, along with whites from the U.S. and overseas, seeking adventure or a solid paycheck.

At Hoopa and the vast majority of other sites, Native and non-Native employees ate together at an integrated employee mess, and spent many of their off hours together. They threw Halloween and St. Patrick's Day dances. They organized reading clubs, social clubs, musical reviews, and going away parties. And they celebrated weddings.

Indian Service workplaces, with their many single men and women, became hotbeds of romance, sometimes across racial or tribal lines. One employee of the Santa Fe Indian School joked, "It is said that the atmosphere of the school room is infected with the most contagious form of matrimony. Never in the history of the school, has one of its teachers left the institute unmarried." The same could be said of employees at Hoopa Valley. In 1900 Frederick Snyder, the "desperately popular" white clerk at the agency, married Miss Charolette Brehaut, the white school matron. Other weddings paired Native peoples with whites, or with those from different tribes.

The Indian Service has left its mark on Hoopa Valley and the Hupa people in ways it never would have imagined. If somebody had told service officials at Hoopa Valley a century ago that in 2011 the Hupa nation would not only still exist, but continue to live on the banks of the Trinity River, holding sacred dance ceremonies, fishing for salmon, and managing businesses and a museum, they would have been shocked. The service's primary goal was to put an end to tribes and their traditions and it pursued that goal with great force. And yet over and over, the legacy has been something different, a testament to the persistence and creativity of those who struggled against it.

The men and women who used service jobs to stay anchored in Hoopa Valley gave birth to politically active generations. The sons and grandsons of James Marshall, who worked in the service in the 1880s and ‘90s, served as tribal council representatives over several decades. One son, Edward Marshall, represented the tribe at meetings with federal officials during the 1930s regarding the government's decision to recognize tribal governments through the Indian Reorganization Act. The Marshalls also helped keep the Hupa culture alive by collaborating with anthropologist Pliny Earl Goddard. In his book, Hupa Texts, Goddard warmly thanked James and Mary Marshall, their son Julius, and several others federal employees for "the difficult task of preserving the language and lore of their people."

Martha Chase, who eventually retired to Los Angeles, would certainly not have seen her life's work as a vital contribution to basket making. But by finding buyers for the artisans, she helped those women maintain traditional knowledge and pass it on to their daughters and granddaughters. Today, the northern branch of the California Basketweavers Association is based out of Willow Creek, just upriver from Hoopa Valley.

Sherman Norton's son, Jack Norton Sr., later went to the Haskell Indian Boarding School at Lawrence, Kan., where he fell in love with a Cherokee woman named Emma. They married and he attended Northeastern State University in Tahlequah, Okla., becoming one of the first Hupa tribal members to go to college. After he graduated, he and his wife joined the Indian Service, working first in Oklahoma near her family and later in Navajo Country. Although he was raised in the Hupa cultural traditions, Jack Jr. remembers his mother reminding her children of their Cherokee heritage as well. He also learned about Navajo traditions while they lived in the Southwest. Soon after, the Nortons returned to Hoopa Valley and later Jack Sr. served as one of the tribal chairs during the 1950s, helping the tribe avoid termination -- when the federal government once again tried to get rid of Native nations by ending the legal relations between tribes and the federal government.

These experiences may have influenced Jack Jr. when he began to study and write Native history, eventually going on to help found Humboldt State University's Native American Studies Department, established in 1998, the only stand-alone program of its kind in the California state system. If Sherman Norton's goal was to remain connected to his tribe and culture when he fought for fair pay nearly 100 years ago, the choices of his children, grandchildren and beyond suggest he was successful. Despite the government's intense efforts to destroy Indian people's loyalty to their communities and traditions, despite the fact that both Sherman Norton and Jack Norton Sr. had been sent to boarding schools and worked for the Indian Service, the Norton family is still here, and still committed to their culture.

Historian Cathleen Cahill, who grew up in Bayside and graduated from St. Bernard's High School, first became fascinated with the Indian Service in the mid-1990s. Her aunt and uncle gave her the memoir, In the Land of Grasshopper Song, and she was hooked. "I just had never heard of anything like it," Cahill said last month, during a book signing at Eureka books. The institution that tried to destroy Indian ways became the subject of her master's thesis, her doctoral dissertation, and her just-published book, Federal Fathers and Mothers: A social history of the United States Indian Service, 1869-1933. Cahill, an assistant professor of history at the University of New Mexico, has drawn on her years of research for this article.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4