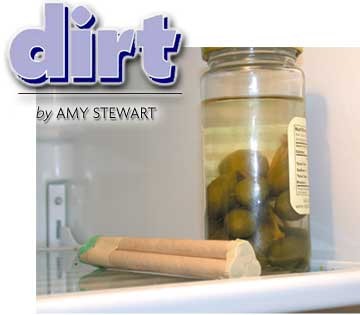

- Hibernating bees in tubes, kept in Amy's refrigerator. Photo by Amy Stewart.

I've been away from the garden too long. After a couple of months on the road, the place is a mess. Those hard freezes back in January turned some of my favorite shrubs into popsicles, but somehow spared the weeds, which have taken over. I've got some serious garden restoration work to do - and I'll be back in a couple of weeks with some ideas for how to replace the tender plants that many of us lost to frost this winter.

But before I get back to pulling weeds, I've been eager to do something about the bee situation in my garden. The New York Times has been running dire news stories about the disappearance of honeybees from hives and the declines in native bee populations. Nobody's sure about the cause. Some blame mites and fungus, others suspect pesticide use, pollen from genetically-modified crops or global warming. The disappearance of bee habitat - meadows, forests, even flower gardens - has been cited as a possible cause as well. Whatever the reason for the decline, I decided that I needed to do something about the bees in my own backyard.

I'm not talking about honeybees here. The bee that lives in a hive and produces honey is Apis mellifera, a familiar European species that is perfectly delightful, but it represents more of a commitment than I was willing to make. I can barely manage a flock of chickens and a bin of earthworms, so I decided I'd better not take on a hive.

Instead, I was interested in mason bees, those solitary foragers that wander around the garden, pollinating flowers and building nests in hollow reeds or bits of rotting wood. These bees don't live in colonies, they don't produce honey, and they won't sting unless you step on them or attack them violently enough to deserve such a response.

Mason bees belong to the same family as leafcutter bees, another solitary native species that turns up in my garden every year to cut perfect round holes out of the leaves of my rose bushes. I don't have the heart to object; the sight of bees flying around with little bits of my rose garden in their grasp is far too entertaining. They're welcome to whatever they can get. Besides, they use those bits of leaves to help build a nest for their young. If I've learned one thing from my friends who have children, it's that you should never get in the way of a determined mother when she's decorating the nursery.

So with those leafcutter bees in mind, I stopped by the Knox Cellars booth at the Seattle garden show in February. They sell bee boxes - wooden blocks with holes drilled in them at the precise size that the bees prefer for their nests - and they sell the bees themselves, in hibernating form. I watched one of the company's owners carefully slice open a paper straw - the bees are sold in straws and kept refrigerated until it's time for them to hatch - and reveal a pupa that was ready to emerge. It took just a little prompting for the bee to get free of her membrane and to sit on her liberator's hand, stretching her wings and considering the strange surroundings she'd found herself in. "It'll take her a few minutes," the guy said, "but she'll get her bearings and fly off." Sure enough, after just a minute or two she got tired of her crowd of admirers, and flew off in the direction of the display gardens. I was hooked.

But I didn't buy the bees in Seattle, figuring that I should wait until I was home for good. I had no idea that a couple of New York Times articles would create a run on bees, but sure enough, by the time I got home last week, Knox Cellars had sold out of bees. (You can visit them online at knoxcellars.com, but forget about ordering mason bees from them this year.)

Fortunately, Strictly for the Birds in Eureka came through for me. They were also sold out of the orchard mason bee, Osmia lignaria, which emerges in early spring in time to pollinate fruit orchards. But they did have a few tubes left of Osmia californica, a warmer-weather bee that needs to stay in the fridge until late May when the temperatures are high enough for it to hatch.

A set of tubes retails for twenty-five bucks, and that guarantees you at least twenty bees. (I know what you're thinking. You know you're a gardening addict when you will pay a dollar for a bug. I can't help it; I had to have them.) Buy them along with a nesting block, and those bees will, with any luck, stick around and raise a family. Other solitary bee species, like my beloved leafcutters, might take up residence there too, and all of these bees are perfectly capable of getting along together and sharing the space.

Right now, our bees are in the fridge, next to the martini olives, waiting for May. We've got the bee box mounted in a sheltered spot on the kitchen porch, tucked up under the roof, just above the worm bin. Between the bees and the worms, it's getting a little crowded out there on the porch. Just wait until the New York Times convinces me that I need to do something about ant diversity in my garden, and I have no doubt that I'll be setting up an ant farm out there too, and paying a buck apiece for some fantastic native ant species. Go ahead and laugh. At least shopping for bugs keeps me out of trouble.

And once my bees hatch, what will they eat? I'll be back in a couple of weeks with some ideas for plants that will lure bees and tolerate the next cold snap. Stay tuned.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1