On a summer day in 1969,Bob Rowen, a nuclear control technician at the Humboldt Bay nuclear power plant, realized that for his employer, Pacific Gas and Electric, the bottom line was everything — it was even more important than the community's safety.

It wasn't the first time Rowen, a burly former Marine, had witnessed safety violations at the plant, but it was the first time he had the gumption to record the violation in a logbook, which would eventually be reviewed by the nuclear industry's then government watchdog the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

As for PG&E management, they were getting pretty fed up. Rowen was proving to be a real pain in the ass.

On Aug. 6, an 80-ton lead-shielded container arrived at the power plant to transport spent nuclear fuel across the country to New York State for reprocessing. The cask was placed into the plant's spent fuel pool and spent fuel rods were secured inside. When it was lifted out, it was drenched in radioactive water, which had to be hosed off and the entire cask scrubbed down with alcohol and detergent so that it would be clean enough to ship. Problem was, no matter how hard the techs scrubbed, they kept getting readings that were way above the Department of Transportation radiation limits. They staggered their coffee breaks so that the decontamination process could go on non-stop. But even that wasn't enough — the cask was still "crapped up." In some places it gave readings of 4,000 to 6,000 disintegrations per minute per 100 square centimeters (more than twice the federal limit). At the seal, it read 20,000 per minute.

Holding the cask over for another day would have cost the company an extra $70,000. Rowen's supervisor, Gail Allen, came up with a solution. He took samples from the cask using a very light touch and recorded measurements just outside the federal limit. Then he told Rowen to sign the release papers.

Shortly after doing so, Rowen recorded the incident in the plant's radiation control log: "G. Allen asked Rowen to sign the release papers for the spent fuel shipping cask stating that the contamination level of the cask to be less than 2,200 disintegrations per minute, when in fact, they were greater than 2,600 disintegrations per minute ..."

Rowen had worked his way quickly up the ranks at PG&E from a laborer to a nuclear control technician, the person responsible for maintaining the plant's monitoring system. He didn't realize it at the time, but by recording the shipping cask incident in the plant's logbook, he had signed away a promising career in the nuclear industry and set off a chain of events that would end with his discharge from the company in 1970. In the eyes of his supervisors, Rowen would later reflect, his safety consciousness was tantamount to industrial sabotage. The local police would be called in to investigate him, and he and his so-called co-conspirators would be branded dissidents.

The day after the shipping cask incident, Plant Engineer Edgar Weeks called Rowen into his office. "I reminded [Rowen]," Weeks wrote in a confidential memo, cited in William Rodgers' 1973 book on corporate malfeasance, Corporate Country, "that he had a responsibility to promote harmony, not disrupt it."

In the 1960s on a bored day in Humboldt County you could drive out King Salmon Avenue to the nuclear power plant — Humboldt Bay Unit No. 3 — and see where your electricity came from. There was a visitor's center complete with mockups of the plant informing you how cleanly and efficiently the facility ran. And after a brief orientation, you could take a tour. There was even a viewing gallery that overlooked the control room of the nuclear unit, where the control operator, some nuclear and chemical engineers and a couple control technicians — Bob Rowen, perhaps — were busy helping America kick its dependency on foreign sources of energy.

"Anyone who criticized [PG&E] was criticizing America," an older, wiser Rowen recalled last month.

The Humboldt Bay nuclear plant, which went live in 1963, was the first commercial boiling water reactor west of the Mississippi and therefore a test case for the industry. But only a year into the plant's operation cracks had already begun to show in the stainless steel cladding that housed the nuclear fuel pellets. The plant produced electricity by heating water into steam, which drove a turbine — in newer, cleaner nuclear facilities, the steam that runs the turbine doesn't come from water directly heated in the reactor core, but by water heated in a secondary loop.

When Rowen started working at the plant in 1964, just nine months after it opened, nuclear energy was "cutting-edge stuff — a new frontier," he explained. "It represented to me, as a young man, a promising future." And Rowen seemed like an industry poster child: a 20-something veteran and former semi-pro football player, clean-cut and hardworking.

But Rowen wasn't on the job long before he started noticing inconsistencies between plant protocol and things he'd learned in the Marines, where he received nuclear weapons training. In particular he was confused by PG&E's sanguine take on exposure to low-level radiation. Rowen copied down a passage from a PG&E textbook he'd been given when he started working. It read, "There is no evidence that shows that continuous low-level irradiation contributes any appreciable amount of life span shortening." He contrasted that with a passage from a book he found at the Humboldt State University library, Radiation: What it is and how it affects you: "Small doses of radiation below the permissible levels produce significant though small depression of the white blood cell numbers. ... Although the very small changes in blood-cell numbers do not seem to produce any immediate ill-effects, they may be the forerunners of anemia, leukemia, and other serious and fatal blood diseases."

When Rowen brought this up at work, he was discouraged from pursuing the matter further. He just assumed that doing his job right entailed making the plant safer and cleaner. But as far as plant management was concerned, the take-charge attitude Rowen had learned as a Marine Pathfinder (a Green Beret-like unit) ought to be kept in check.

"I started to ask questions which were met with a lot of resistance," Rowen said. "I never found a way to question anything with PG&E. There was the PG&E party line, and that was it."

At the same time, the plant itself started coming apart almost as soon as it was built. Cracks in the reactor's cladding meant that in 1965 the facility was releasing almost twice as much radioactive vapor per second as was permitted by the AEC (now known as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission). By 1966 the plant was operating at just 40 percent of rated capacity. Eventually, the cladding was replaced with a more expensive material, zircaloy, but not before radioactive vapor had already been spouted out the plant's stacks and carried downwind to who knows where.

A public opinion poll from February 1956 showed that 69 percent of Americans had "no fear" of having a nuclear power plant located in their community. By 1978, things had changed drastically. A poll of college students and members of the League of Women Voters in Oregon were asked to rank thirty sources of risk "according to the present risk of death from each," and both rated nuclear power as number one, more dangerous even than handguns, motorcycles and smoking.

What happened in the intervening two decades? Accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl had yet to occur. The change in public opinion can be attributed in part to former employees of the nuclear industry like Bob Rowen, who, acting in the best interest of their community rather than their employer, went public with information about unsafe practices going on inside nuclear power plants. Still, as a new decade dawned, Rowen had no idea that the peaceful atom wouldn't remain peaceful for long.

The August 1969 incident with the lightly swabbed shipping cask was far from the first time Bob Rowen had noticed that plant management was habitually cutting corners.

One of the many safety violations Rowen noticed and would later report to the AEC, was the practice of feeding test rabbits — meant to graze on the grass just outside of the power plant — store-bought pellets so as to water down measurements of radionuclides coming from the facility. PG&E insists they were concerned only with the animals' welfare, fearing they'd go hungry without the supplemental feed.

On another occasion, Rowen discovered that a painting crew had come and gone from the plant and been contaminated with radioactivity. He insisted, as was company policy, that their homes and cars, as well as the stores they'd patronized in the meantime, be visited and checked for contamination. PG&E said that checking their cars would suffice.

Similarly, Rowen once discovered that radioactive metal had been hauled away to a local scrap yard. He stressed that it was the plant's duty to go and find it and dispose of it properly. But the last thing PG&E wanted to do was to scare the public by sending out a bunch of guys in hazmat suits, armed with Geiger counters.

At South Bay Elementary School, located just a quarter mile downwind from the plant, there was a dosimeter for measuring radioactivity. Dosimeters were located at sites all across the region, but the elementary school site — site 14 — consistently showed the worst contamination. PG&E's solution was to take the dosimeter down permanently. When Rowen asked why, management told him he was "overstepping his boundaries."

In 1970, Rowen noticed hot particles on plant workers' shoes. He hypothesized that when high-level waste was literally being tossed into concrete storage vaults located outside the facility, some of the bags broke open sending particulate into the air. When he presented his concern to plant management, they told him it was more likely fallout from Chinese nuclear tests. Rowen still doesn't buy it.

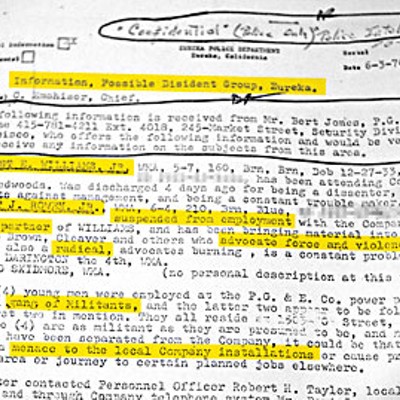

That same year, PG&E finally found a good enough excuse to let Rowen go. At a safety meeting, he and coworker Forrest Williams accused management of intentionally setting the plant's hand and foot counters high. The counters were used to screen employees for radiation before leaving the plant. The next thing Rowen and Williams knew, they were being interrogated by PG&E security chief Bert Jones, who came up from the company's San Francisco headquarters. Rowen later told Ramparts magazine that Jones "wanted to know why we were trying to demean management and instill unfounded fears in the minds of other employees." Jones then got in touch with Eureka police chief Cedric Emahiser and asked him to prepare a police report on the plant's troublemakers, who included not just Rowen and Williams but two other men as well — Raymond Skidmore and Howard Darrington.

The police report reads like a throwback to the McCarthy Era. Its contents were based entirely on information PG&E, through Jones, fed to Police Chief Emahiser. It stated that Williams was a dissenter and that Rowen was his "clone partner," who had brought books by Rap Brown and Eldridge Cleaver, and others "who advocate force and violence" into the plant. (Rowen recalls that the books were required reading for a class he was taking at College of the Redwoods at the time.) Rowen, it said, is also a "radical" and "advocates burning" — a reference to his military training in demolition.

The police report was never intended for public scrutiny. Rowen saw it only because it was leaked to him by an acquaintance in the police department. He later successfully sued the City of Eureka for access to the report, at which time its contents were made public. When it was first written, it was sent to various Eureka city officials, PG&E's San Francisco office and a local FBI agent. The intent, according to Rowen, was to blacklist the four PG&E employees, to prevent them from ever again working in the nuclear industry. Nonetheless, Darrington and Skidmore continued on with PG&E.

Williams was fired on May 25, 1970, and Rowen was let go shortly thereafter, on June 5. PG&E claimed that Rowen had threatened to break his boss Edgar Weeks' arm — a claim Rowen still denies to this day — and that he was guilty of general harassment of the company.

"I suppose in their minds they thought I was harassing them in some way, in terms of raising issues concerning radiation protection safety, threatening to go to the Atomic Energy Commission and other outside agencies," Rowen later told the Times-Standard.An Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board found that Rowen's "extreme safety consciousness" was the real reason he was fired. And later, the Humboldt County Grand Jury commended him for his "continued and determined effort in bringing this situation to the attention of the public." Nonetheless, PG&E continued to refer to him in press releases as a "disgruntled former employee," and they've never apologized for their conduct.

Edgar Weeks passed away six years ago. And his wife declined to comment on the Rowen affair when reached at her home last month. (When I first got in touch with Rowen by phone in February and introduced myself, there was a long pause on the other end. Having not done all of my homework first, I wasn't aware of the baggage my last name carried. Once I reassured Rowen that I was not related to his former supervisor, his voice relaxed somewhat. Still, there was a hint of paranoia. Blowing the whistle, I would soon learn, was perhaps the most difficult mission this former Marine ever undertook.)

After he was fired, Rowen filed numerous allegations of safety violations at the power plant with the AEC. The agency, whose ranks were notoriously filled with former employees of power utilities, conducted their investigation and concluded that PG&E hadn't done enough to make sure its employees weren't being overexposed to radiation, that there was a potential for the contamination of the area's domestic water system from the plant and that Rowen had been discouraged from talking to the AEC. Rowen described the probe as a "public whitewash and a utility wrist-slap."

Edith Kraus Stein was a student at South Bay Elementary School when the nuclear reactor first went online in 1963. Later in life, she developed a rare form of lung cancer, linked, she says, to radiation exposure. Speaking to me from her home in Louisville, Ky. earlier this month, Stein, whose breathing was at times audibly labored because she only has one lung, said she still believes that the power plant — which Science magazine once called the "dirtiest" in the country — was the reason for her cancer. "We were in spitting distance of that plant and I think it did have something to do with it," she said. She also cited the removal of the dosimeter from the school grounds as evidence that the utility had something to hide.

In 1986, Stein asked the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors to investigate whether or not there was a causal link between the nuclear power plant and what she said, based on anecdotal data collected from former classmates and school employees, were numerous incidents of rare forms of radiation-induced cancers. A study focusing on the incidents of cancer in downwind communities has never been conducted even though the Redwood Alliance, a local renewable energy advocacy group, applied for a grant to conduct one in the late '80s. They based their grant application in part on an analysis of National Cancer Institute (NCI) data by Humboldt State University professor Charles Chamberlain. It was Chamberlain's contention that the NCI data warranted a more in-depth, local study.

Later, in 1991, a broad study conducted by the NCI itself found no general increased mortality risk from cancer of people living in 107 U.S. counties containing or nearby 62 nuclear facilities. Humboldt County was included in the study. Still, Stein says that doesn't mean that the power plants didn't cause cancer. Cases like hers, in which no one died, wouldn't have shown up in the NCI report.

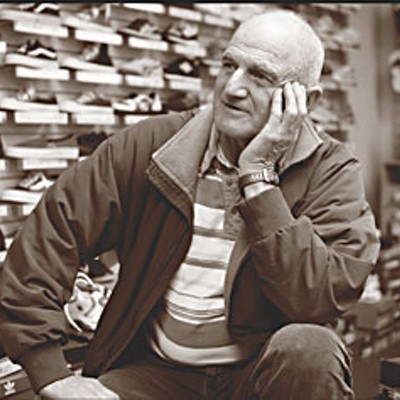

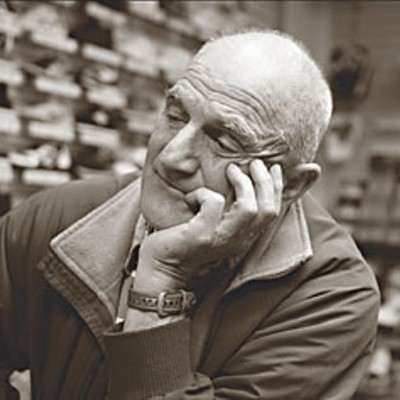

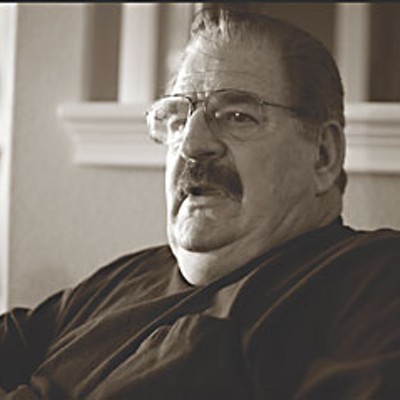

Rowen has gotten slightly rounder with age but still cuts an impressive figure for a 67-year-old. The once cleanshaven nuclear control tech now sports a professorial, shortly cropped mustache. Filling up an oversized sofa chair in his suburban home in Redding last month, he spoke with the ease and clarity of the seasoned teacher he eventually became after he left PG&E.

"I don't have nearly as much faith in my government as I did when I was 21 and coming out of the Marine Corps," Rowen said, reflecting on the events surrounding his discharge from PG&E almost four decades ago. It was a subject that he hadn't thought about in a long time. It was also something his wife didn't want him to talk to a reporter about because she didn't care to dredge up the past. But Rowen still thinks it's important for people to understand that in the final analysis "you really can't trust corporate America to do the right thing ... or government."

"When I served in the military I had a view of honor, discipline, pride and respect," he said, "but I learned later on that those ideals that I subscribed to were misplaced."

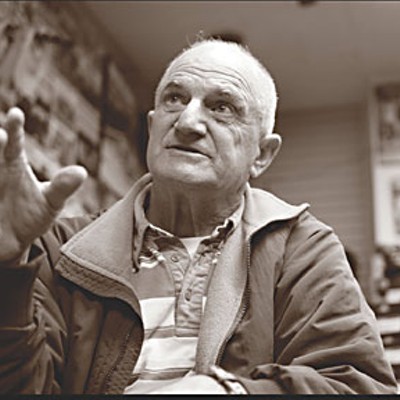

When I asked 74-year-old Forrest Williams about his opinion of corporate America earlier this month in his son's Arcata shoe store, he said, "I don't think you can trust them." It was after-hours. Williams, just a sprinkling of white hair left on top of his head, sat on a rolling stool with a Nike swoosh on it; boxes of shoes were stacked up all around, and half of the lights in the shop were turned off.

"They knew they were cutting corners," he said of PG&E. "They knew they were doing it. I don't think they considered the safety, as far as exposure ... it was that attitude. As long as the law allows it we can do it, and fudge on it a little."

"I couldn't have stood what he stood," he said, remembering his old friend and coworker Rowen. "Being an ex-Marine he was tougher than I was. He had been trained in that area, how to absorb interrogation without getting brainwashed or beaten down."

Williams was in the Navy too. An electronics technician, he watched almost a dozen atomic weapons tests from the deck of a Navy fleet tug. But the Navy, he says, was far more careful than PG&E ever was in terms of the precautions it took to minimize radiation exposure.

"PG&E had an altogether different philosophy," he said. "The government gives you a maximum exposure allowable and you use it like a speed limit. What you do is if one person gets up to the limit, find another body and run them up to the limit. They were really ignorant as far as trying to avoid exposure."

Williams was given his job back at the plant after arbitration, but he quit on the first day because PG&E refused to do anything about the slanderous police report they'd commissioned. "I wasn't gonna go back and work for a company that had tried to discredit me and where I couldn't trust my welfare, personal safety," he said.

Williams made a point of never working for a big corporation again. "PG&E was an outfit where your job was supposed to mean more than your life," he said.

Raymond Skidmore still lives in the area. The 74-year-old has suffered from a stroke and pancreatic cancer since retiring from PG&E a decade ago. Reclining in a La-Z-Boy chair and dressed in a sweat suit, he spoke to me earlier this month in his Eureka home. He was there that summer in 1969 when Allen took intentionally light swabs off of the spent fuel casks. As for why he was never fired, "[PG&E] probably figured Rowen was the leader, causing all the trouble," Skidmore said, and then his voice trailed off and he looked away. He didn't seem too keen on remembering the past.

However, he did mention that even after Rowen and Williams left, unsafe practices continued at the plant. He kept a logbook where he recorded safety complaints, which, coincidentally, went missing the day he was scheduled to talk to a representative from the AEC. "There were just a few of us who tried to do the job right," he said.

As for Rowen, he ended up moving to Weaverville where he went to work for the Trinity Union High School District as a teacher and a football coach, and then later as an administrator. During his 32 years of service he was named coach of the year and teacher of the year. Rowen doesn't regret the stand he took against PG&E. And though he remains firmly opposed to nuclear power, in large part because he lost his faith irrevocably in corporate America after his experience with PG&E, he's still optimistic about the future. "In our human community, truth will ultimately prevail," he said towards the end of our conversation last month in Redding.

When we were done talking, he poured himself a glass of red wine and we rummaged through half a dozen boxes of records relating to the power plant he had collected over the years. They were things he hadn't looked at since the late '80s. When he found the EPD police report, the veins on his neck bulged.

"PG&E has got to come to terms with what it is that they did," Rowen said. "They've got to admit wrongdoing, and they're not going to do that ... I'd like to think they would. I'd like to think there's a whole new generation of PG&E corporate management that would say, 'Maybe there is something to all this. We're going to look into it, and now that we've looked into it, [we admit] the company did not act properly in the Bob Rowen case.'"

Last week the Journalasked PG&E for an official response to the Rowen affair. We supplied the company's spokesperson with background information on Rowen, including old newspaper and magazine articles, since she had never heard of him before.

On Tuesday, Peter Resler, Director of Nuclear Communications for PG&E, said via e-mail that he was unable to "speak about specific personnel issues, even those that happened over 30 years ago."

"What I can tell you," he said, "is that safety is one of our core values throughout PG&E. Our 'Zero in on Safety' program sets the standard for every PG&E organization — emphasizing that whatever the nature of the work, the first and most important outcome is that employees remain injury free throughout the preparation and completion of their jobs."

In 1979, moviegoers went to the theaters to see The China Syndrome, a fictional story about an enthusiastic nuclear technician, Jack Godell, who realizes that his employer, the California Gas and Electric company, is more concerned about losing money than running their plant safely, and whose warnings to the public are dismissed as the ranting of a madman. In the end, Godell gets it, literally. CG&E bring in a Los Angeles SWAT team to rub him out. Though the movie differs in its details from Bob Rowen's story, the overall arc rings uncannily true. Concerned nuclear technician branded disgruntled worker. Cover up. Move on.

Luckily, PG&E has changed a great deal since Rowen and Williams were fired, according even to those locally who are opposed to nuclear power. Michael Welch of Redwood Alliance and Mike Manetas, an anti-nuclear activist and former lecturer on energy issues at Humboldt State University, are pleased with how PG&E has dealt with spent fuel from the nuclear plant, which was shut down in 1976 after a previously unknown fault just off the coast was discovered. The spent fuel will be placed in dry casks as early as this spring and left on site, according to Welch.

"They've become more open in the community since those days," Welch said last week in his Arcata office, located in a building on G Street that runs entirely off of solar power.

Manetas agrees. "Today, PG&E and the people down at PG&E who are working at the power plant are very, very competent and concerned and recognize that removing the spent fuel and decommissioning that power plant is a very, very serious technological undertaking and that they will do the best that they can," he said earlier this month.

The makeover is industry-wide. Proponents of nuclear power are touting it as our natural next step, a clean, endless supply of energy. And they've latched onto fears of global warming and concerns over the skyrocketing price of oil to usher energy consumers into a new nuclear century. They also argue that today's reactors are far cleaner and more economic than the dirty, atavistic behemoths of yore.

In their promotional materials, the Nuclear Energy Institute, the leading lobby group for the U.S. nuclear industry, points out that America's nuclear reactors already produce 20 percent of the electricity we use, and according to the Department of Energy, electricity demand will rise 45 percent by 2030.

In another brochure aimed at debunking myths about radiation, one section header reads, "Radiation: Helping All of Us." The brochure, which features a nuclear family of four watching the sunset at the beach cites the 1991 National Cancer Institute report, which indicates no increased rate of mortality in communities with nuclear power plants.

But Manetas and Welch don't buy the hype. They argue that a lack of economic viability has and always will be one of nuclear power's biggest drawbacks. A nuclear power plant is very expensive to build, Manetas said, and even more expensive to decommission. The Humboldt facility is a case in point. It cost $33 million to construct and he estimates the price tag for decommissioning to be around $380 million. Every nuclear facility across the country has a lifespan of about 30 years. Manetas argues that without significant subsidies from the U.S. government, nuclear power plants wouldn't be able to break even.

There are also hidden costs to nuclear energy like dealing with the waste it produces as well as extracting and processing the uranium required to run the plants in the first place. "Eventually power plants would be cannibalizing themselves," Manetas said, "producing just enough energy to produce more power plants."

As open as PG&E has become over the years to the local community, Manetas is still concerned that "floating over that is cooperate PG&E." The company owns and operates one of California's two remaining nuclear power plants, the Diablo Canyon facility in San Luis Obispo.

How would someone like Bob Rowen expect to be treated at a nuclear power plant today? Manetas speculates that "his ability to whistle-blow and make that information public ... is more viable in today's environment."

Still, Manetas warns that there is a nation-wide nuclear renaissance underway, and the zeitgeist could quickly change back to what it was when Rowen first started working at the Humboldt Bay nuclear power plant. That was a time when the nuclear industry was anxious to prove that their energy prices could compete with those of fossil fuel plants, and they had few qualms about silencing their naysayers.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4