It's a Sunday afternoon in late July, and Janet Smith stands in her kitchen, surrounded by oak cabinets, shiny black appliances and flying-saucer looking chandeliers. When she opens the Macy's box on her table, white packing peanuts spill out, no longer needed to cushion a small package of Estee Lauder bronzer. Smith has wondered about those peanuts -- "Is this stuff recyclable?" Uncertain, she tosses them. She knows the box can be recycled, though, so she breaks it down and stuffs it in her recycling bin.

The 32-gallon bin is almost full of plastic jugs of Minute Maid juice, some jars of margarita mix, laundry detergent bottles, magazines and newspapers. She'll roll the bin out to the end of her driveway later tonight. Tomorrow afternoon, a Recology truck driver will park outside her house on Leslie Road in Eureka, hurl the recyclables into the belly of the truck and haul them away. But to where?

All over the United States, recycling facilities process our boxes and jury summons letters, our beer and water bottles, our milk jugs and take-out containers. They turn what could have been trash into cash, selling it in a marketplace that people are skittish to talk about. One of the key stops en route to that resale market is the recycling center -- and in Humboldt, that has been a complex and conflicted staging ground.

[][][][]

Managing Humboldt's recycling has been a cauldron of drama for years. The Humboldt Waste Management Authority -- a joint powers authority made up of representatives from the county and most of its cities -- once took its recyclables to the Arcata Community Recycling Center. That $8 million dual-stream processing plant in Samoa, and its smaller predecessors, had handled most of the county's recyclables for decades. But after the center started charging a $65 a ton tipping fee in 2010, the waste authority looked into two options -- buying the recycling center or finding a lower cost site once its contract expired.

Amid accusations and threatened lawsuits, members of the Waste Management Agency found a new recycler. In 2011, Eureka, Ferndale, Rio Dell and Humboldt County signed a five-year contract with Solid Waste of Willits, which offered to pay $8 a ton for the privilege of hauling the stuff off and sorting it. Arcata and Blue Lake stuck with the Arcata Community Recycling Center, calling it a vital community resource. But after losing its biggest customers and dealing with bond debt, the center struggled. It shut down early this year. (One of its smaller properties, a collection site on 10th Street in Arcata, may soon be sold to Eel River Disposal of Fortuna.)

With the big Samoa recycling site closed and its 30 former employees out of work, the Waste Management Authority now has to figure out what comes next. The contract with Solid Waste of Willits can be canceled with six months' notice. That contract is an "intermediate solution," said HWMA interim president Patrick Owen, and the public and the authority's board members will have to decide what comes next. It's highly unlikely that could include buying the shuttered Samoa plant, Owen said. A strategic planning public work session is scheduled for Thursday, Aug. 23, at 5:30 p.m. at the Humboldt Bay Aquatic Center, 921 Waterfront Drive in Eureka. The meeting will include input from R3, a Sacramento-based consulting firm that's helping the board develop a waste management plan. Owen said the HWMA hopes to make a decision by June.

Humboldt's recycling angst comes as county residents have joined masses of Californians who are trying to wring a little more life from what once would have been tossed. According to state department CalRecycle, California led the nation in 2010 by diverting an estimated 65 percent of its trash away from landfills. That's a huge flip flop from the 1960s, when a Los Angeles city ordinance requiring people to separate tin cans from the rest of their garbage caused such an uproar that Sam Yorty rode into the mayor's office on a promise to reverse it. (LA didn't return to recycling until 1993, according to its Department of City Planning website.)

[][][][]

It's just after 2 p.m. on Monday, and Leonard Wonnacott turns onto Leslie Road in Eureka. He's been working for garbage companies for 30 years and is nearing retirement. Wonnacott stares at his side mirror through his tinted, transition lenses and snuggles Recology truck #13207 beside Janet Smith's recycle bin. The $320,000 truck offers a steering wheel on both sides, and Wonnacott chooses to drive from the right. He firmly grabs the three toggle switches in the center console and begins to flick the black-knobbed levers back and forth. Compressed air hisses with each thrust.

Shhhhhp, left toggle -- the robotic arm extends toward the bin. Shhhhhp, center toggle -- the jaws open. Shhhhhp, left toggle -- the arm extends a bit more. Shhhhhp, middle toggle -- the arm clasps the bin. Shhhhhp, right toggle -- the skeletal arm violently lifts the bin 30-feet in the air.

The diesel engine quakes the truck. A small black and white monitor next to Wonnacott's steering wheel displays what's going on behind him. He sees that the bin has reached its pinnacle and tips it over. The plastic flaps slam open and the truck swallows Janet Smith's Macy's box and her other recycleables. Wonnacott shhhhhps the toggles, this time in reverse order, and the bin dives to the ground and sticks the landing like a gymnast. He's already done this more than 500 times today.

Wonnacott, a stout man in his 60s, has been snaking through Eureka's neighborhoods along a route designed by a software program called RouteSmart, which displays city grids in colorful, pictorial maps. He started at 6:30 a.m. A city ordinance forbids Recology -- which operates Eureka's curbside recycling service -- from collecting in residential areas before 6 a.m. Arcatans don't get to hit the snooze button. The city hasn't instituted any such restrictions, said Rick Fusi, owner of Arcata Garbage Co. He said some of his haulers start at 3 a.m. Maybe that's why so many Arcatans cover their windows with thick layers of blankets?

With his route now complete, Wonnacott drives toward the HWMA's recycling facility, next to Harbor Lanes bowling alley in south Eureka. The station has drop-off areas for garbage, recycling, green waste and hazardous waste. The garbage goes to one of two landfills, either near Redding or Medford, Ore.; the green waste to Mad River Compost in Arcata; the hazardous materials mostly to the Bay Area; and the recyclables are separated out for their trip to Willits. This center is what people in the industry call a MRF (pronounced "murph"), materials recovery facility.

Wonnacott arrives at the center and rolls onto the 70-foot scale. The station weighs trucks before and after they unload to calculate how much recyclables they drop off. HWMA charges commercial trucks a $120 tipping fee with each dump. The operator gives the signal and Wonnacott drives into the center's warehouse.

Inside is organized chaos. A two-story-tall heap of garbage sits along the south wall, while a mound of recyclables about equal in size sits closest to the entrance on the west end. A black-and-yellow Caterpillar 950 front-end loader zips around the facility like a mechanical bumblebee, flying from pile to pile, tidying up the throwaway loot. The operators wear neon-orange vests and matching hard hats, clear protective glasses and radio headsets. They're constantly in motion, but never in each other's way.

HWMA operations manager Helder Morais (the "H" is silent), a short and muscular man with dark eyes, commands the flow from his walkie-talkie. With a wad of chewing tobacco under his bottom lip, Morais tells the excavator driver, "All right, looks good, let her down."

Wonnacott pulls into the warehouse and rolls down his window, trading his regular wisecracks with Morais. Even jokes are recycled here.

Wonnacott makes a three-point turn so that the rear of his truck faces the recyclables pile. He pushes on the gas at a formidable speed and slams on the breaks, ejecting the cardboard and mixed paper into the mound. He dumps the containers with a hydraulic lifter that tilts the load onto the floor. It's his second dump today. This load turns out to be a little more than two tons (the trucks can hold about four). Four Recology trucks collect the county's and Eureka's recyclables every weekday; each truck will unload once or twice a day. Two to three Arcata Garbage trucks each drop off a load a day too.

Janet Smith's Macy's box isn't visible amid the Pepsi bottles, Slim-Fast cans, lawn furniture, strawberry containers and Cheetos bags. There is no hierarchy among the trash at the recycling center. The Budweiser bottles and the bottles of Robert Goodman wine all end up here and are valued about the same.

"This place is a bank," Morais says as he scanned the hills of trash and recyclables. But it's not making HWMA rich. Most curbside recycling programs are not financially self-sustaining. The cost of collecting, transporting and sorting materials generally exceeds the money generated by selling the recyclables. That's why customers are charged a monthly rate, which hovers around $23 dollars a month for standard service in Eureka and Arcata. But the money earned on the market helps keep rates down.

Back in the warehouse, an excavator opens its jawed bucket, bites into a heap of recycled goods -- there's an awful lot of pizza boxes in there -- and spews it into a 57-foot trailer, which takes 20 minutes to fill. The trailer is loaded with four bales of aluminum too, each weighing about a ton. They sit on the bottom like silvery ice cubes. About 15 to 17 tons of loose material -- cardboard, glass and plastics -- is thrown on top of the cubes. Federal laws restrict trailer weight, and Richardson Grove restricts length, for now anyway.

This is trailer #114 and it belongs to Solid Waste of Willits. HWMA brings in about 154 tons of recyclables a week and most of that is exported 142 miles south to Willits. Whatever Willits can't handle, which isn't much, C&S Waste Solutions in Ukiah gets. An even smaller portion of the recyclables at HWMA is sold on the commodities market to brokers or directly to manufacturers. When HWMA does trade on the market, it generally sells a few bales of mixed paper to International Paper (check the bottom of your brown-paper grocery bags, and chances are there's an International Paper stamp there), which is then most likely sold to a pulp mill in Springfield, Ore.

Solid Waste of Willits hauls five to seven trailers every week from Eureka. Before it landed the HWMA contract in 2011, the company was already bringing woodchips to Scotia every week and the trucks were heading back to Willits empty. So now, after stopping in Scotia, the drivers travel a little farther north and pick up a trailer of recyclables, then head back to Willits.

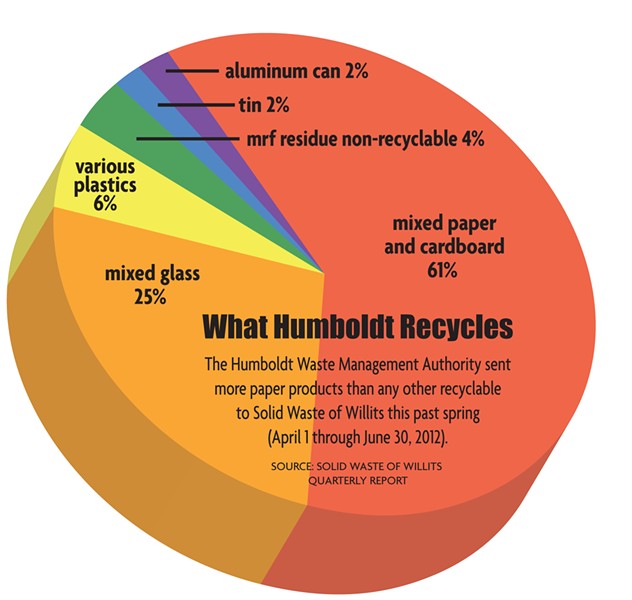

According to a quarterly report from Solid Waste of Willits, between April and June the company received 1,695 tons of recycled materials from HWMA and has paid the authority $85,180 for those materials and loading fees.

[][][][]

It's almost 90 degrees in Willits and Juan Gamez, site manager for Solid Waste of Willits, enjoys the comfort of his air-conditioned office. Plaques of the company's industrial achievements hang on the wall and a framed picture of his sons' soccer team sits on his desk. He monitors the activity in the warehouse from his flat-screen TV on the wall. It shows the loading dock, the main floor and the single-stream recycling processor - a beast of a machine, almost entirely blue except for the yellow trim on railings, steps and ladders. It stretches along the south end of the building and continues halfway along the east wall. It was installed less than four years ago. When it's turned on, employees wear earplugs. Birds used to flock to the machine until the company hammered in nails, points up, onto the surfaces.

A truck arrives and reverses into the warehouse, dropping 15 tons of recyclables from Humboldt onto the main floor. It joins the mountain of other materials in a pile about twice as long as the heap at HWMA. The materials are about to be shoved and jostled through single-stream recycling, a process that has largely edged out the dual-stream recycling that the Arcata Community Recycling Center had been so proud of. In dual stream, paper takes a different route from the remaining plastic, metals and glass. That requires more sorting at home and more expansive trucks.

Once on the main floor, a front loader pushes a bathtub-sized pile of recyclables onto the conveyor belt. The belt steadily carries the materials up several stories until it plateaus. At the top, nine employees wait to sort the material; it's a marriage of man and machine.

Up here, the belt stretches flat for about 60 feet. The first line of men -- yes, they're all men in these jobs right now, although women have been on the line in the past -- stand across from each other on opposite sides of the belt. Their hands rummage through the materials, darting, slamming, grabbing. Workers go through two pairs of gloves a week. They pluck out milk jugs and laundry hampers, otherwise known as natural plastic number two. The men toss the jugs down the chute and into a collection bay. Five feet down the line, another pair of men do the same thing, except they're removing laundry detergent bottles, oil and antifreeze containers, the colored number two plastics. The last pair of men pull out tin. It's a lot of soup and instant coffee cans.

Like priests, therapists or film developers, recycle sorters get an intimate look into our personal lives. They're archeologists of the living. And what do they deduce from what we're throwing away?

"We see a lot of sex toys. A lot!" says Gamez, a short man who suddenly gains a few inches with his bright-yellow hard hat on. Dead animals, wedding rings and passports have all passed through the line too. Once a bag of bundled $20s came through. "But no bodies," Gamez jokes, his smile exposing his bottom-bracket braces.

After the materials pass the men, the belt dips down. Glass drops into a container directly below. The leftover materials then climb a motorized screen. The syncopated rattling makes them jump up like popcorn kernels. The screen allows paper to move on while unwanted waste materials fall through the cracks. The surviving mixed paper and other residual materials make a U-turn, riding along the black-rubber conveyor belt a few dozen feet before they are met by the critiquing eye of another sorter. He lets magazines, Bibles and letters pass through and removes anything that's not paper, which is mostly plastic bags at this point. The paper rides the belt a few feet farther before it falls down a chute. The machine operates like an occult hand, cradling the good while swiping away the bad.

The plastics and tin that the men threw into collection bays will be emptied and baled. Residual materials that fell through at various spots take another ride along the belt for a second sort. Now the remaining materials are ready to be baled. According to a Solid Waste of Willits report, only 4 percent of the materials brought to Willits can't be recycled. That's pretty good by industry standards; Owen said some centers can't recycle up to 30 percent of what comes in.

Now that it's all sorted, it's time for packaging. Different recyclables, each at its own time, travel on a baler conveyer into a hopper, where they're compressed by a giant ram and bundled by a wire machine that wraps metal at 50 feet per second. It expels the bundles in cubes about the size of a small refrigerator, and depending on the material, weighing anywhere from a half to a full ton.

Sometimes the baler gets jammed when too much paper gets in. To fix the jam, a brave employee must descend into the depths of the baler and stare down that ram, which is designed to crush cars. There's a whole protocol. The machine must be turned off, and the keys that would restart it must be in the pocket of the employee entering the baler. No one else can be around the machine and every lock mechanism must be initiated. And you thought sticking your hand in the garbage disposal was scary.

Bryan Smith has been working at Solid Waste of Willits since he was 17. Eight years later, he's now the operations manager. He admits that he used to mindlessly throw stuff in the garbage. But that's changed now, and he helps his wife with the recyclables at home.

Smith points to a stack of baled aluminum cubes near the loading dock. "They turn out so pretty looking." Later this week, shipping containers will pick up a lot of these pretty looking bales Smith has put together. Some of those containers will have Chinese lettering on them.

The Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, a trade association with more than 1,600 member companies, reports that the U.S. processed more than 134 million metric tons of recycled materials in 2011, valued at about $100 billion. That's pretty close to Apple Inc.'s $114 billion total revenue last year.

The materials were sold to manufactures in the U.S. and more than 160 other countries. China has the largest appetite for our recycled materials, especially our paper and cardboard. The country doesn't have the infrastructure to harvest its own recycled waste yet, but it's quickly building recycling centers to do so, according to Jerry Powell, editor at Recycling Resource. The U.S. exported $8.5 billion worth of recyclables to China in 2011. Canada is second on the list, receiving $3 billion of our recycled exports, and South Korea third with $1.7 billion. (Roughly $60 billion of the materials stayed within U.S. borders.)

At this point, the quest to track exactly where Janet Smith's Macy's box and the rest of Humboldt's recyclables end up becomes murky. We can guess with some probability where it goes, but we can't be certain.

Here's the problem: Brokers buy these materials and sell them to, well, anyone, anywhere. They might buy a container of mixed paper from Solid Waste of Willits for $100 per ton and flip it to the highest Chinese buyer for $110 per ton.

Several brokers bragged about how many buyers they had in their Rolodexes. But none of them offered names. They wouldn't even offer a ballpark number.

"I'm not going there. Don't even ask," said Melvin Weiss, an independent broker from the wealthy Bay Area suburb of Danville, who's been in the business for decades. His jovial tone quickly turned skeptical after he was asked which companies he brokered with. "The minute something like that gets out, my buyers could be flipped." There are 40 other guys waiting in line for every brokered deal, he said.

Weiss is probably right. I called a Los Angeles broker I thought traded with recycling centers across the North Coast. Turns out he didn't, but he demanded I tell him the names of the centers so that he could solicit them for business.

When deals are done, it's the Jerry Maguire principle of capitalism: Show me the money. Show me the most money.

"He who pays the most gets the material," said Brian Sollum, operational manager of another North Coast garbage and recycling company, Humboldt Sanitation. According to Sollum, Humboldt Sanitation collects about a fourth of the county's recycled goods, in McKinleyville, Trinidad and east toward Hoopa. It requires customers to do most of the separating of their recyclables, and has onsite staff that divvies up the rest. Since the ACRC closed, Sollum said Humboldt Sanitation has seen more than a 40 percent increase in volume.

The business deals Sollum secures with brokers are never long-term contracts. "I've never had a contract in 27 years," he said. "If you're smart, you play one broker off the other: ‘Pony up or I'll ship to Joe.'" It's the same story for all of the North Coast's recycling centers. Contracts are for big companies capable of offering a ton of tonnage, not the smaller operations common in Humboldt.

Like many industries, the recycled commodities market ebbs and flows with the global economy's influence. Earlier this month, Solid Waste of Willits sold mixed paper at $105 a ton. The following week the price fell to $75. Prices are so low for aluminum right now, a material that is generally a money maker for recycling companies, that Harry Hardin is holding onto at least 100 tons of the stuff. He'll sell it when the price is right. Hardin owns Eel River Disposal, a material resource facility in Fortuna with a single-stream recycling center. The company is close to wrapping up a deal to purchase the Arcata Community Recycling Center's drop off site on 10th Street in Arcata (not to be confused with the ACRC's dual-stream recycling center in Samoa).

Amid the secrecy and swiftly made deals, here's what we do know about some of our recycled materials: Aluminum stays domestic. Humboldt, your cans go to the Bay Area, most likely to Anheuser-Busch's recycling center. The company's plant manager said the aluminum bales are then sent to the Midwest or the East Coast to be melted and made into sturdy sheets. It's then recycled into a Budweiser beer can. Again.

Your glass, that's staying right here in California too. Glass is a proverbial loser, essentially subsidized by the state through California redemption value (or CRV) deposits, said Sollum. Humboldt, for the most part, your glass goes to Strategic Materials in San Leandro. According to the company's website, its "specialty ground glass products are used by customers as beads for reflective high striping, frictionators for bullets and matches, grit for dental products" and as ingredients in ceramic floor tiles, bricks and pots.

Your mixed paper is mostly being shipped offshore. Powell said there's an 80 percent chance of it ending up overseas, mostly in China, South Korea and Taiwan. And old corrugated containers, which areyour basic cardboard, have a 50 percent chance of being exported. There are still some paper mills along the West Coast that are keeping paper domestic. Several centers in Humboldt said they're taking their paper to Springfield, Ore., where it's made into a pulpy oatmeal material used for new cardboard boxes. A broker for International Paper Inc. said that the life of cardboard, from when it's kicked to curb to when it becomes a new box again, can be about six weeks.

Your plastics, there's about a 50 percent chance that's being shipped to China, said Powell. Although Eel River Disposal said a buyer in Sacramento takes most of its plastics, that could just be a middleman. Sorry, Humboldt, this one is too tough to call.

And those packaging peanuts Janet Smith had wondered about. Turns out they are recyclable. In fact, according to Macy's website, those peanuts are 100 percent biodegradable. You can dissolve them in water and pour that into your garden, yard or toilet. But they can also be dropped off at Post Haste Mail Center in Arcata. Reuse is the quickest route to recycling.

Comments (6)

Showing 1-6 of 6