In March 1850, the brand-new California Supreme Court, Chief Justice Serranus C. Hastings presiding, issued its first-ever decision. The ruling freed seven men who had recently been charged with arson and murder and instead placed them under a $10,000 bond.

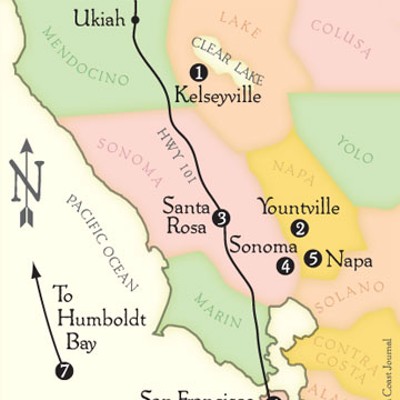

The men were released from the USS Savannah, a naval vessel anchored in San Francisco Bay. They’d been imprisoned there after a ride of death and destruction through the Sonoma and Napa valleys during which they killed numerous Indians and burned their rancherias. The raiders were led by brothers Sam and Ben Kelsey, who were bent on avenging the death of another brother, Andy, and his partner, Charles Stone.

Five of the seven didn't make it to their next court date. They jumped bail and traveled north on important business: They were headed to Humboldt Bay to help found the town that became Arcata.

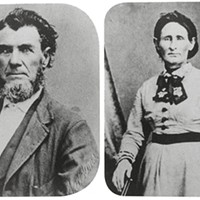

The Kelseys were already well known in northern California. Ben and his wife, Nancy, arrived there with the Bidwell-Bartleson Party in 1841, and Nancy was reputedly “the first white woman to cross the plains to California.” Ben and his brothers subsequently participated in the Bear Flag revolt of 1846, which ended Mexican control of California and established the short-lived “California Republic.” It was Nancy who sewed together the new country’s first flag, which was supposed to show the republic’s emblem, a grizzly bear. To some observers, however, the animal looked more like a pig.

In the fall of 1847, Andy Kelsey and Charles Stone started a ranch at Clear Lake, where they reportedly “employed” several hundred of the local Pomo Indians. The partners mistreated their workers and paid them almost nothing. The next year, Ben Kelsey, ever anxious to find his fortune, established a mining camp called Kelsey’s Diggings in the Sierra foothills. With Sam Kelsey and some other whites as assistants, Ben collected between 50 and 100 Pomos to work at the mine site. Once back at the diggings, Ben had a better idea. He sold all the company’s supplies at a profit and then, ill with malaria, headed back to his home at Sonoma. The Pomos, forced to camp near a hostile group of local Indians and suffering from malaria themselves, were left on their own. According to one report, only three of them survived.

Back at Clear Lake, Stone and Andy Kelsey continued abusing the Indians, who finally attacked the ranchers. Word reached Ben and Sam Kelsey, who recruited several supporters and arrived in time to drive the Indians off.

Nothing changed at the ranch. One Indian worker, who’d let a raccoon ruin some the ranch’s watermelons, was killed for his negligence. Whites who visited Stone and Kelsey’s place reported “that it was no uncommon thing for them to shoot an Indian just for the fun of seeing him jump.”

Ben Kelsey also dealt death to the Pomos. When his wife Nancy rode to Sonoma to fetch medicine for her ailing husband, she was accosted by an Indian but managed to escape. She reported the incident when she arrived in town; her attacker was captured and sentenced to a hundred lashes. Then, according to Nancy, “I returned home with the medicine for my sick husband, but instead of taking it, he rode into town and shot the Indian dead.”

In the fall of 1849 the Pomo workers again attacked the ranch. This time they killed both Stone and Andy Kelsey. Andy Kelsey’s brothers took revenge -- on an entirely different group of Indians. In late February, as reported in the Daily Alta California, two bands of armed horsemen assembled at Sonoma. One group rode off and murdered “a large number of Indians” in the lower part of the Napa Valley. The other party, “headed by Samuel Kelsey and a Mormon named Smith,” started near Yountville and burned and killed their way south, pausing long enough in Sonoma to announce that they would “hunt and kill every Indian, male and female, found in the country.” The citizens of nearby Napa “saw the bright blaze of the burning buildings which lit up the opposite side of the valley” and decided to act. They quickly formed an armed company that “repelled” Smith and Kelsey’s raiders.

The next day Sam Kelsey and six others were arrested in Sonoma and jailed at Benicia. Several other riders were named but not charged with any crime, while a third group, including Ben Kelsey, was to “be admitted to bail.” The “Sonoma Seven” were incarcerated on the Savannah while their case was argued before the California Supreme Court.

The justices faced a dilemma. California was not yet a state. It had no jails, no established system of jurisdiction, and no set of clearly defined laws. In short, it lacked a system that could hold, try, convict and punish criminals.

The Supreme Court played for time. It ordered the release of the seven raiders but required them “to post good and sufficient sureties in the sum of $10,000” and to appear, when ordered, in Sonoma District Court to stand trial for murder.

Fat chance. Especially since a means of quickly leaving the area -- and the opportunity to make a small fortune in land speculation -- had just presented itself.

Only weeks earlier, four battered riders arrived at Mrs. Mark West’s ranch, north of Sonoma. One of them had been badly mauled by a bear and needed a place to recuperate.

The victim was Lewis Keysor (L. K.) Wood, recently of the Gregg Party, a group of eight explorers from the Trinity River mines who the previous fall had set out for the coast in hopes of finding a supply port for the miners. After many weeks struggling through daunting terrain, they succeeded; they beheld what was to become Humboldt Bay, which hadn’t been visited by a white man for more than 40 years. The party then headed south to bring their news to San Francisco.

What had already been a difficult trip turned into a disaster. The party, beset by internal strife, had a climactic quarrel at their crossing of the Eel River. They broke into two groups, one headed by the original leader, Josiah Gregg, the other by Wood. Gregg’s reduced party started down the coast; they eventually turned east and reached Clear Lake, where Gregg died of starvation. His companions found their way to Sacramento.

Wood’s group, which went up the Eel and then the South Fork, did little better. They encountered snow on the ridges and nearly impassable terrain along the river. When they returned to the high country, Wood was attacked by not one but a pair of grizzlies -- one grabbed his shoulder, the other his ankle. They tugged on Wood for a while, “as if,” he said, “to drag me in pieces.” Then the bruins departed, leaving Wood with a dislocated hip and the place with a new name -- the Bear Buttes. In excruciating pain, Wood thought he might be left to die. Instead, his companions took him south to succor at the West Ranch. The rest of Wood’s party then went on to San Francisco, where their report of the rediscovered bay created a furor.

So it was that two days after the Alta California reported the release of the Sonoma Seven, the paper carried an eye-catching front page ad: “For Trinity Bay -- The fast sailing schooner jacob m. ryerson ... will sail for Trinity Bay and Trinity River on Sat., the 23d.” Two of Wood’s companions, Thomas Sebring and Isaac Wilson, formed a company to take passage on the Ryerson. At least three of the Sonoma raiders, Joseph Smith and brothers Arthur and Julius Graham, had recently left another, more stationary, vessel -- the U.S.S. Savannah. Just now, they were especially interested in finding a “fast sailing” ship.

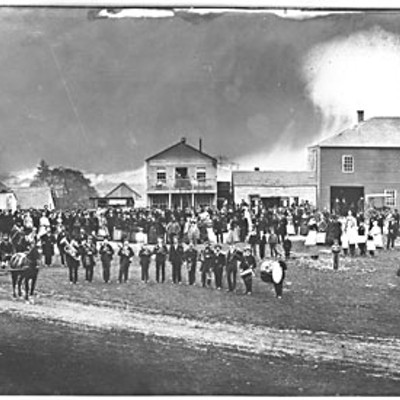

After an eventful trip, which included sailing into the mouth of the Eel River (Captain William Tichenor mistook it for the Trinity) the Ryerson’s passengers arrived at Humboldt Bay. Four members of what would become The Union Company stopped at the spot where Gregg Party member David A. Buck had carved his initials on a tree the previous December. The other Unionites continued to the head of the bay, where they spent three days laying house foundations and locating land claims. On April 27, 1850 they wrote up an agreement describing their intent.

The “Union Company,” as they called themselves, was establishing a town called “Union.” There were 33 names listed, including some, like L. K. Wood, who were yet to arrive. Ten of the 33 members had been implicated in the Sonoma-Napa Indian attacks.

The company, strongly influenced by its contingent from the Sonoma gang, immediately began to cut a wide swath down the eastern shore of the bay. Not content with their own townsite, they also claimed the right to settle father south, at a location that the competing Mendocino Exploring Company also sought. The two groups reached a compromise, and the Mendocino group soon surveyed the first streets for the town they had just named Eureka.

Farther south, David A. Buck had returned to the location of his carved tree. He found a log cabin on his “claim,” constructed by H. Nelson Lloyd, a member of the Union Company. Lloyd had since headed north to the Union townsite, and Buck proceeded to build his own dwelling. Upon learning this, the Union Company met to consider Buck’s impertinence. A resolution was proposed “to drive him off and if necessary to kill him.” However, some members of the company threatened to “stand for Buck and help him hold the place,” and the terminator faction of the group backed off. Buck’s “place” presently became Buck’s Port and then Bucksport. Buck, however, enjoyed only brief celebrity. He soon left the area and proceeded to drown off the mouth of the Columbia River in 1852. His property became part of a tangle of competing claims, some traced from the Union Company, which grew so complicated that by 1909 as many as seven different “owners” were paying taxes on a single Bucksport lot.

The long arm of the Union Company extended even farther south, to the fourth community on the bay, Humboldt City. In early April Hans Henry Buhne had landed at a nearby bluff (today called Spruce Point) with members of the Laura Virginia Company. This group proceeded to establish a townsite, but it was impeded by the presence of a large Wiyot Indian village, Djorokegochkok (pronounced, approximately, Chaw-ro-ke-utch-kuk). However, a solution to the problem soon presented itself.

In mid-May the schooner Eclipse stuck fast on a sandbar in the bay. Several whites came aboard and stripped the ship of most items of value. Then a few Indians rowed out and removed some residual sails and ropes. Some men from the ever-acquisitive Union Company heard of the incident and came down the bay to “hunt for the stolen property.” Joined by other whites, they induced a member of the Laura Virginia Company, Harry La Motte, to engage a couple of young Wiyots to help them locate the goods. This the boys did, taking the men to Djorokegochkok. There were no Indians at the village. Henry A. Weatherbee, one of the whites present, indicated that the men found articles from the Eclipse and then “we burnt all their huts and other property, fishing apparatus, baskets, provisions, etc. and returned home.”

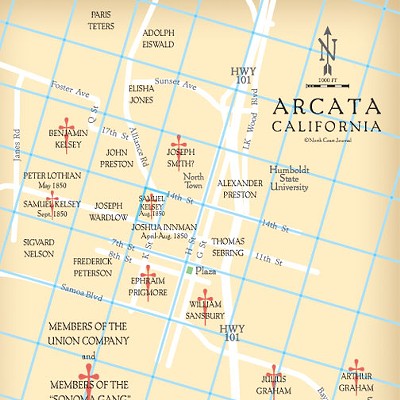

But there was more to it than that. La Motte, writing years later, disclosed that one person from the raiding party did more than help burn the village. William H. Sansbury, a member of the Union Company who was also a Sonoma raider and the father-in-law of one of the Kelseys, looked at the two young Wiyot guides and said, “I judge these fellows know too much about this, we may as well leave them right here.” He drew his pistol and shot the boys dead.

The Indians, their village burned and two of their people murdered, subsequently retaliated, killing two whites from the Eel River, described by La Motte as “perfectly harmless fellows,” who had the misfortune to be alone at the wrong place and time. The whites along the bay plunged into a panic, imagining that the attack was the start of a war of retribution. During the frenzy, a canoe full of Wiyots was observed crossing the bay to the peninsula. The whites saw this activity by the Indians as “preparatory to their general onslaught upon the settlers.”

The response was to launch a preemptive strike. About a dozen whites requisitioned a whale boat and, under cover of darkness, set out for the supposed war camp. The leader of the raiding party was a man of experience -- Joseph Smith, a member of the Union Company and one of the accused murderers who’d been jailed on the Savannah. Smith proved an incompetent leader, but the attackers nonetheless accomplished their aim. Several Indians were killed and the village plundered and then burnt. Twice, within a year of their arrival, members of the Sonoma gang had murdered Indians on Humboldt Bay.

The Kelseys were not around at the start. They had lingered in the south until August 1850, when a letter from Eureka noted that “Kelsey, of Sonoma, (the Indian killer) is on his way here with his own and several other families….” Nancy Kelsey claimed that they “did not see a white person on the trip. Some Indians opened fire on us, but my husband killed the chief and the rest retreated.”

By September the Kelsey brothers were playing their roles as founding fathers of Union. Ben held land where the Simpson Mill was later located, north of Foster Road. Brother Sam, who was not a member of the original Union Company, had purchased property directly south of Ben’s and also owned a smaller parcel just southwest of Arcata High School. Other Sonoma raiders held nearby parcels. “Captain” Joseph Smith, who led the massacre on the peninsula, claimed the area around Sunset School. Ephraim Prigmore had located north of Samoa Boulevard, where the California Barrel Company later had its mill. William S. Sansbury, who killed the first two Indians on the bay, held what became the Plaza and lands southeast of it. Julius Graham, who’d been on the Savannah, occupied the area around the Arcata sports complex, while his brother Arthur, also late of the prison ship, owned much of what became Sunny Brae. Most of the fledging town belonged to the Sonoma Indian killers.

L. K. Wood, once he arrived on the scene in September, must have been appalled to learn of the composition of the Union Company. He later wrote that “four of the recruits were arrested for murder (Indian killing)….(Six should have been arrested, and five of the six hanged, as they never quit Indian killing, but kept it up after reaching here, which was the first cause of our Indian troubles.)”

Most of the Sonomans did not stay long enough in Union to see it become Arcata. Local historian Susie Baker Fountain remarked that “it is comforting to know that the undesirables soon returned to Sonoma and that Captain Smith passed away in 1855.” Some of the undesirables sold their property for a profit. But the Kelsey brothers, who’d come north to get rich, did the opposite.

Ben Kelsey acquired a lot at the northwest corner of today’s Plaza and built big. He created a splendid house that John Carr in 1853 found to be “the best private dwelling I had yet seen in the State.” With the large domicile came a huge bill for its construction. Kelsey soon saw his mortgage foreclosed, and when Carr beheld the building it had a new owner, Isaac Nixon. Sam Kelsey also defaulted on a note and lost his Arcata holdings.

By 1861 Sam was in San Bernardino County, where he formed a band of Confederate sympathizers. A warrant was issued for his arrest in February 1862, but he “slipped through…[the] fingers” of local authorities and vanished from the historical record. Ben and Nancy moved from place to place. Ben died in Los Angeles in 1888, while Nancy lived out her last days near the Cuyama River east of Santa Maria. She died in 1896 and was later honored for her flag-making activities as “the Betsy Ross of California.”

For its part, Union soon became the foremost town on the bay. It not only offered the shortest shipping route to the inland mines but, when Trinity County was partitioned in 1853, it became the first seat of newly created Humboldt County. Elected as the first County Clerk was a member of the Union Company who’d stayed around -- L. K. Wood.

In 1856 Union decided to incorporate. On May Day of that year, the new city received two pieces of important news, one bad, the other dreadful. First, the California Supreme Court ruled that Union’s incorporation required legislative approval, which, however, had not been obtained; Union was therefore merely a town and not a city. Second, the legislature did act on another matter -- it had transferred the county seat from Union to Eureka.

Union, twice diminished, had to wait two years, until 1858, before the legislature deigned to grant it cityhood. Then in March, 1860, the legislature noticed the community again. Responding to a petition from citizens of Union, it changed the city’s name to Arcata.

Another name had previously been proposed, by none other than L. K. Wood. When he had first passed down the bay with the Gregg Party in December 1849, Wood noted a Wiyot leader who came from the doomed village of Djorokegochkok. The man’s name was Ki-we-lat-tah, but he was often called “Old Coonskin” for the cap he wore to cover a badly healed head wound. Wood described Ki-we-lat-tah as “an elderly and dignified and very intelligent Indian. He appeared very friendly and seemed disposed to afford us every means of comfort in his power.” The Indian offered the bedraggled explorers “a quantity of clams upon which we feasted sumptuously.” So impressed was Wood that when the opportunity arose, he urged that the Union Company name their newfound town “Ki-we-lat-tah.” Given the attitude of some of the group’s members, it was no wonder that the suggestion was rejected.

But along with his bear-scarred arm, Wood still had a trick or two up his sleeve. When he established a ranch on the western edge of Union/Arcata, he named the place Ki-we-lat-tah. Wood kept track of the elderly Indian and noted in 1856 that the Wiyot leader was still “living on the bay and has always been a quiet and friendly Indian.” In October 1873, a group of ranchers and farmers met at Wood’s ranch to form a chapter of the Patrons of Husbandry. They elected Wood -- who would die the next year -- the organization’s first Master. They also agreed to the name that was no doubt proposed by their host: the Kiwelata Grange.

It was only a small gesture of respect and gratitude, but after the darkness of the Kelseys and the following darkness of Indian Island, a small shaft of sunlight had at last shone down upon the people -- Indian and white -- of Humboldt Bay.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1