In 2013, what's become known as the third wave of the national opioid epidemic began to wash over the United States. But fueled by the opioid fentanyl, for years it didn't hit Humboldt County, leaving residents and officials to read about its devastating impacts elsewhere as it came to dominate national overdose rates. Then in 2019, it hit Humboldt County like a sneaker wave, entering the drug stream hidden in various forms, from pills to powders and seemingly everything in between.

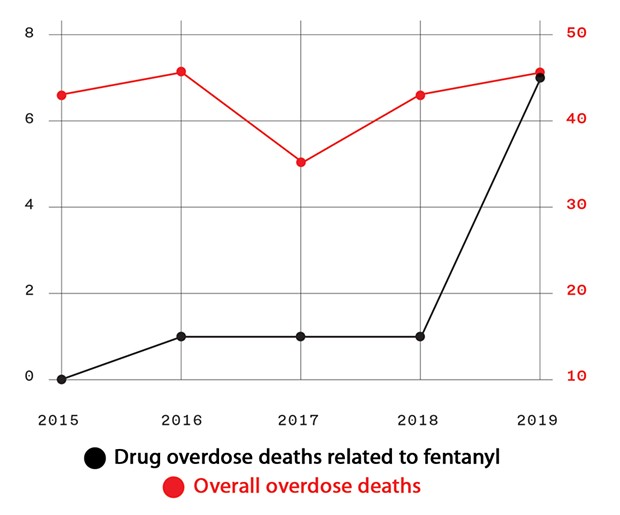

Fentanyl — a synthetic opioid that's as much as 100 times stronger than heroin — was virtually unheard of in Humboldt County just a handful of years ago. In 2015, none of the county's 43 overdose deaths tested positive for even a trace of the stuff, according to Humboldt County Sheriff's Office Lt. Sam Williams, who heads the coroner's division. The county found it in the toxicology results of one overdose victim each in 2016, 2017 and 2018. Then, last year, seven of the county's 46 overdose victims had ingested fentanyl in some form.

"Something changed," Williams said. "It's a marked difference."

The victims of the seven fatal fentanyl overdoses in Humboldt County — five men and two women — ranged in age from 25 to 44. In a couple cases, fentanyl was the only drug found in their systems. In others, it was mixed with morphine, alcohol, methamphetamine or alprazolam, a generic form of the benzodiazepine Xanax. But it was the last case of the year that thrust the issue into public view, with a 39-year-old man overdosing on a mix of fentanyl and cocaine at an Arcata house party on New Year's Eve.

Arcata Police Lt. Todd Dockweiler said the death came in conjunction with another near fatal overdose in which paramedics were able to revive the victim using the opioid overdose reversal drug Naloxone. In both cases, APD learned the users were unaware they were ingesting fentanyl.

"They thought they had just purchased cocaine and really were unaware that it contained fentanyl as well," Dockweiler said. "Folks using cocaine who are not opioid users, it hits them hard. It's a tolerance issue."

That tolerance issue is particularly acute with fentanyl due to its incredible strength, the great variance in dosing and the way it's cut into other substances, from cocaine and heroin to counterfeits of prescription pills like Xanax and OxyContin. But it's the drug's strength that makes it so dangerous. Consider this: while medical doses of narcotic medications like morphine and hydrocodone are given in milligrams, medicinal doses of fentanyl are generally doled out in micrograms. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, a lethal dose of heroin is generally considered to be roughly 30 milligrams, while a 3-milligram dose of fentanyl — which looks like a few grains of salt — is enough to kill an average adult male.

"A very, very small amount can be lethal," said Williams. "When you're dealing with micrograms, it's not something your average person knows how to measure safely or accurately."

Humboldt County Drug Task Force Supervisor Sgt. Jesse Taylor agreed, saying that using fentanyl to stretch or cut black tar heroin — which originates in Mexico and is the most common variety in Humboldt County — is especially dangerous. Because the drug is so potent, he said it needs to be blended throughout evenly, as any fentanyl pockets could deliver a lethal dose.

"If you hit a spot that's concentrated fentanyl, that's when people overdose oftentimes," he said, later adding that by the time heroin arrives in Humboldt County, it's been "stepped on and cut" so many times, it's hard to tell where in the supply chain fentanyl is introduced.

Fentanyl's potency coupled with its synthetic nature means it can be produced incredibly cheaply. As Taylor said, while heroin is derived from "a long, expensive process to extract opium from poppies," fentanyl can be made anywhere from a variety of precursor chemicals.

- Source: Coroner’s office © 2020 Jonathan Webster / North Coast Journal

- Drug overdose deaths related to fentanyl & overall overdose deaths in Humboldt County

In his 2019 book Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic, Ben Westhoff chronicles fentanyl's global supply chain. The vast majority of the precursor chemicals needed to make it originate in China. In some cases, laboratories there actually make fentanyl that's re-routed through other countries and shipped into the United States in the mail. But in most cases, those chemicals are shipped to Mexican drug cartels, which manufacture fentanyl in large quantities and either smuggle it over the southern boarder, or sell it on the dark web and ship it to clandestine laboratories in the United States.

Because fentanyl is so cheap to produce and potent, and there are no quality controls in illicit markets, dealers have begun repackaging it as a variety of substances.

"Raids across the United States have turned up operations in houses and apartments that turn fentanyl powder into tablets using specialized presses," Westhoff writes. "Both the drugs and the machines are bought from China. These operations can make thousands of pills per hour. They stamp pills with the OxyContin or Percocet logo, and they're indistinguishable. ... The dosages of these fake pills vary greatly. One might have 10 times as much fentanyl as the next. Investigators believe such counterfeit pills were responsible for the death of music star Prince; about 100 white pills found on his property looked exactly like Vicodin but actually contained fentanyl."

Candy Stockton, the chief medical officer at the Humboldt Independent Practice Association and and co-chair of Rx Safe Humboldt, said fentanyl's presence in the counterfeit pill market is incredibly scary. First off, fentanyl's incredible potency can easily lead to overdoses when the user is intending to take an opioid and has built up a tolerance. But even more dangerous is when a user is intending to take something else — anything from Adderall to Xanax to Ativan — when they don't have a history of taking opioids or a built up tolerance.

"If you're buying prescription pills (illicitly), more often than not they're counterfeit," Stockton said. "And more often than not, the prescription pills people think they're buying have fentanyl in them."

Williams said that he didn't have enough information about Humboldt County's fatal overdoses in 2019 to say how many may have been the result of counterfeit prescription pills, but toxicology results for four came back negative for any street drugs.

National data and anecdotal evidence also suggest that heroin is increasingly coming laced with fentanyl, as well. Because fentanyl is so much cheaper to produce, cartels are also increasingly mixing it with heroin to stretch the drug further. Taylor said that task force sources say that most of the heroin bought and sold in Humboldt County does have fentanyl in it.

Interestingly, though, none of Humboldt County's 2019 overdoses came back positive for heroin. It's unclear whether that's simply an anomaly or because regular heroin users have higher tolerances and have also habituated themselves to carry the opioid overdose reversal drug Naloxone.

Stockton and Dockweiler both stressed that there's no harm in administering Naloxone, even if the person overdosing turns out not to have ingested an opioid.

"Even if they've actually overdosed on Xanax, it will not hurt them," Stockton said.

Dockweiler also stressed that people should not delay in calling for medical aid in situations where someone around them might be overdosing.

"Minutes really make a difference," he said, adding that even if people are doing illegal drugs, they shouldn't fear calling police when someone's life is potentially hanging in the balance. "People should have seen by now that when law enforcement responds to something like that, we're not looking to arrest anyone for possession. Those are just medical aid calls to us."

But the biggest takeaway from the spike in fentanyl overdoses nationally and locally, experts say, is that users should recognize they never truly know what they're buying on the illicit market.

"Any drug where it's a powder or a pill, you just can't trust it," Westhoff said in an interview with DigBoston. "There can be fentanyl in anything. ... People don't even realize what they're taking — whether it's heroin, or pills, or cocaine, or whatever."

Dockweiler believes that was the case in Arcata on New Year's Eve. He believes both people who overdosed that night thought they had purchased straight cocaine, which they planned to use during a night of drinking. What they didn't realize is they'd actually purchased a kind of off-brand "speedball," a term typically used to describe a mixture of cocaine and morphine or heroin. The idea is that the cocaine gives the user a slight boost — without getting "too jittered," he says — to balance the drowsiness that follows heroin's initial euphoria.

"As long as I've been in the business, people have mixed cocaine and heroin," he said. "But cocaine is something we don't come into contact with here a ton."

Dockweiler says his guess is that the people who overdosed on New Year's Eve were not "habitual users" and probably didn't have "a dealer." Instead, they probably asked around and ended up buying from an acquaintance who may not have known — or maybe just didn't disclose — that what was being sold as cocaine was actually a speedball that included fentanyl.

"They were not opioid users and not prepared for that," Dockweiler said.

The trend across the country is that when fentanyl shows up someplace, it's not a blip but the beginning of a trend. Westhoff's book highlights the case of St. Louis, Missouri, which recorded just 92 opioid overdose deaths in 2012. That number increased to 123 in 2013, when fentanyl hit the scene, before ballooning to 256 in 2017.

Nationally, there were more than 70,000 fatal drug overdoses in 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control, including 28,000 from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. In 2018, the number of fatal overdoses nationally fell for the first time in nearly three decades, dropping 5 percent. The number of fentanyl deaths, meanwhile, rose to 31,000.

Humboldt County has long had an opioid problem, both with heroin and prescription narcotics. There are some promising signs. While the county once had more opioid prescriptions than residents, those numbers have fallen relatively steadily since 2015 and the county now has about 763 opioid prescriptions per 1,000 residents. Nonetheless, officials fear fentanyl is here to stay.

"Just because heroin is such a hot commodity here, there's going to be a market for this," Dockweiler said. "Hopefully it just goes to people who know what they're getting and are prepared for it."

Thadeus Greenson is the Journal's news editor and prefers he/him pronouns. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Comments