It was Jan. 15, opening day of the Northern California Dungeness crab fishery, and Mike Cunningham's boat, the Sally Kay, was stacked high with pots, ready for the 8 a.m. starting gun. The weather was good as he headed out of Woodley Island Marina. It was still dark, with the first red flush over the hills to the east.

Cunningham's phone rang. It was a friend boating up the coast to set pots north of Trinidad. He had grim news. "There's half a dozen of these big rigs drifting off of Mad River," the caller told him. Cunningham knew the boats; an Oregon seafood company owned them, and they'd been lurking in Crescent City harbor for a month or more. He'd been trying hard to keep them from crabbing in California, and it was a bitter surprise to see them in the area he'd always crabbed, sprinkling the sea floor with their pots, a hundred here, a hundred here, a hundred here.

Crabbers can be a hard-to-please crowd, but the local ones are exceptionally disgruntled this season. They've been cheated, they say, robbed even, by a foul collusion between a dastardly seafood company and the clueless state Department of Fish and Game.

California has only a finite number of Dungeness permits, and they're tied to specific boats. There are no pot limits for now, meaning the bigger the boat, the more pots crabbers can stack on the deck. More pots means potentially more crab. For that reason, it's normally difficult to transfer permits between boats. There are reams of paperwork to slog through, and the new boat can usually only be five feet longer than the old boat. It's meant to keep things on an even keel.

But buried amid the stifling clauses and paragraphs of California legal code is a short section that allows crab boat owners to temporarily lease out their Dungeness permit if their boat is suddenly sunk, burned or otherwise rendered uncrabbable. It's a well-meaning paragraph, but it doesn't stipulate how much longer the boat receiving the temporary permit can be. Not five feet or 10 feet or even 20. That's the key, or some would say the gaping loophole, that opened the floodgates and let the Oregonians come rushing down.

Like just about every other boat owner in Crescent City, Richard Juneau heard about the March 11, 2011, tsunami long before it hit the coast. He hustled down to the harbor, where other fishermen were untying and heading seaward to ride out the waves. He knew he was in trouble. His boat, the Debi J, had a blown transmission. He'd ordered a new one, but it sat, miles away and useless, on a UPS truck in Eureka. "There was nothing I could do," Juneau said.

When the first surge hit, the Debi J bucked its moorings and careened around the harbor, crunching into other boats, getting slammed by other boats. The tide flushed out again, leaving the boat among a dozen or so others dogpiled in the mud. Juneau and another boat owner ran down across the bare harbor bed to try to tie the boats together, to lessen the impacts, but the next set of waves sent them fleeing back up the dock, and the ropes gave way.

By the time the surges stopped, the boat's fishing days were over. The red and white 41-footer didn't sink, but was twisted and tweaked beyond repair. "It bent up everything till nothing would ever line up straight again," Juneau said. He'd been crabbing since he was a young boy, and the loss of his boat left him uncertain of his next move.

Jerry Hampel, meanwhile, had been on the lookout for California Dungeness permits. The fleet manager for Pacific Fishing LLC, a subsidiary of Oregon-based Pacific Seafood Co., Hampel said that early reports suggested most of the crabs this season were creeping around in California. Unfortunately none of the available permits fit his boats, which were bigger and equipped to also catch groundfish and shrimp.

The solution came, Hampel said, when a boat owner from Crescent City called him. It was the perfect let's-scratch-each-other's-backs situation. The guy had a permit, but his boat had been completely ruined by the tsunami. Hampel had the perfect boat, but no permit. And because the boat was destroyed by a tsunami, the boat owner could lease the permit to Hampel for six months, regardless of how big Hampel's boat was.

He offered the boat owner 10 percent of gross on the new boat's catch. Word got around. "It was guys that were hurting," Hampel said. "I figured, well, I can do myself a favor as well as them." By the middle of December, Pacific Fishing LLC had leased five permits.

It wasn't quite that simple, say the California crabbers. The destroyed boats are small -- insignificant minnows in the school of boats. On the other hand, the resident crabbers say, the boats that leased the permits are crab-gulping machines, Dungeness destroyers that leave nothing for the little guys. All the new boats are at least 10 feet longer than the boats they got permits from, and the difference between most is much more than that. One boat, the 33-foot Ruth M., transferred its permit to the 71-foot Coho.

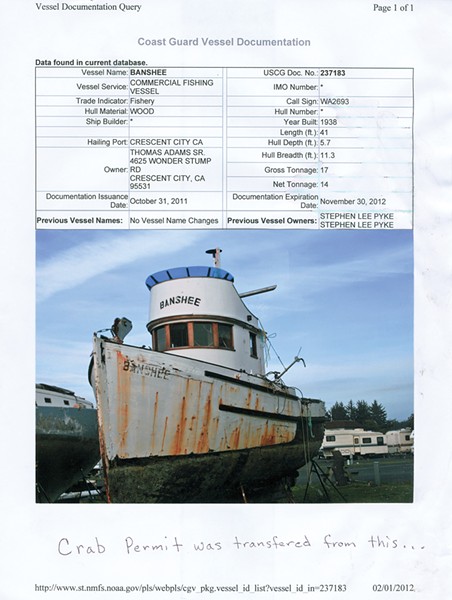

But it's not just the size of the damaged boats that has local crabbers' Grundens in a bunch. Another vexation, they say, is that at least a couple of the boats were clearly not seaworthy even before the tsunami.

"I know the boats that sunk, and they sunk, in my opinion, for a reason," said Crescent City crabber Brett Fahning. He said that the spirit of the emergency transfer provision is clear -- it's a safety net. If there's ever an accident or a mechanical failure or a natural disaster, then it provides a way for crabbers to continue making their living without having to jump through the normal hoops. What happened, however, was plainly not in that spirit, Fahning said.

Randy Smith, another Crescent City crabber, seemed most bothered by the work-ethic gap between the damaged boats and their replacements. Smith said that one or more of the damaged boats hadn't even crabbed for at least the last couple years. To give those permits to the bigger boats was ridiculous, he said, even if it was legal. "All of the boats that were damaged were pretty insignificant in the fisheries," Smith said, "and now you've got these guys on company boats -- they've got a lot of ambition, a lot of drive."

Eureka-based crabber Paul Pellegrini, owner of the 56-foot Celtic Aire, said that the size of the boats didn't bother him, adding that there are plenty of other big boats around. "Our only hang-up with those boats was that the permits came off of boats that haven't fished in several years," Pellegrini said. "I don't have a problem with the biggest boat in the ocean coming up alongside me, as long as they have a legitimate permit."

Cunningham and others tried to stop the leases, sending photos and paperwork to the Department of Fish and Game, but their efforts were fruitless. The department had no legal grounds for denying the temporary transfers, it informed the crabbers, despite their insistence that it did. Jan. 15 arrived, and the tsunami boats, as the locals dubbed them, showed up, decks loaded with pots.

Tension built. The locals suspected the newcomers of scheisty dealings. Their appearance at the mouth of the Mad River on opening day was particularly audacious, said Cunningham. The area, it turned out, had far more crabs at that time than anywhere else. "It was obvious they'd been sampling around," said Cunningham -- illegally dropping pots before the season opening to find the good spots. "They ran directly to a spot where they felt there'd be some crabs."

The big boats also committed the despicable act of pulling up other crabbers' pots to see where the most crabs were, Cunningham said. "We couldn't tell whose pots they were checking, but we could see them doing it."

Then there was the general disrespect, say the locals, who claim the big boats set pots right on top of their pots, cut in line, and flipped them off when they got close.

Fleet manager Hampel said he's only heard of one specific incident, and that bout of name calling was started by someone on a California boat. He said he doesn't know anything about sampling or checking competitors' pots, and he doesn't think his boats were involved. The truth is, both practices are pretty widespread in the Dungeness fishery, Hampel said.

The locals and out-of-towners almost locked claws at least once. Ronnie Pellegrini, Paul's wife, was aboard the Celtic Aire, vacuuming and cleaning while she waited for the next boat in line to finish loading bait at the Pacific Choice dock in Eureka, when she heard a commotion. She looked over and saw Paul in the middle of a small crowd on the dock, staring down a crewman from one of the company boats.

"We were at the fish docks putting bait on the boat," said Paul Pellegrini. "I said something to one of the crew guys. I said, ‘A lot of guys are unhappy with these boats being here, how you got those permits.'" The crewman got all puffed up, he said, and started screaming and hollering. Pellegrini said that he probably should have kept his mouth shut, but he was frustrated. More crew from the company boat rushed over, while dockworkers and one of Pellegrini's crew hurried to lend their aid. "It coulda got ugly," he said. "It didn't, but it could've."

Ronnie Pellegrini grabbed her husband's cell phone and called Rick Harris, manager of Pacific Choice Seafood Co., which has the same parent company as Pacific Fishing. "I said, ‘These guys come into town and get into my husband's face,'" Ronnie Pellegrini recalled telling Harris. "'What's it gonna take?'" She threatened to sell the Pellegrini catch elsewhere if the company boats didn't move or clean up their act.

"Things didn't get off on the right foot," Harris said. He knew the Pacific Fishing boats were coming, but he hadn't foreseen the local outcry. "I didn't realize what an imposition it put on some of the boats in here," he said. He managed to placate Pellegrini, and promised he would do what he could to reign in the company boats. The person to talk to, he suggested, would be Chuck Bonham, the director of Fish and Game, who approved the permit transfers.

Pellegrini gassed up the car and drove to Sacramento to attend the Feb. 2 Fish and Game Commission meeting in Sacramento. After waiting till the end of the hours-long meeting, Pellegrini got her turn to speak. "Thank you, commissioners. I traveled six hours for three minutes of your time," she began. "What I want to talk to you about today is in regard to the tsunami of March of last year." The permits were bogus, she continued -- the boats weren't seaworthy even before the tsunami.

She predicted that approving the transfers this year opened up the door for all the 175 or so boat owners with lightly used, or "latent," Dungeness permits to find or invent something wrong with their vessels in order to lease their permit to bigger boats. "My husband wanted me to pass this on to you. He said he's gonna call his buddy Sig Hansen on the 125-foot Northwestern (of Deadliest Catch fame) and see if he wants to come down here with 2,000 pots and fish Dungeness crab," she said. "That's an example that could happen. We don't want that to happen."

"I'm aware of the situation," Bonham replied. Fish and Game, he said, "will be asking stakeholders to help us tighten up the code to avoid potential abuses in the future." He also said that the department was considering taking legal action in one "particularly egregious instance."

Tony Warrington, assistant chief of Fish and Game's enforcement division, however, said that as of early June, no individuals or boats involved are being investigated.

Fish and Game knew the uproar was coming, Warrington said. After Mike Cunningham and others tried to stop the permit transfers, the department realized that California crabbers probably wouldn't be happy seeing small boats replaced by big boats. Although the department receives a few emergency transfer requests a year, this is the first time that one company has requested a group of them, Warrington said, and it's also the first time that multiple smaller boats asked to lease their permits to bigger boats. Knowing the department could face criticism if it granted the permits, the license and regulation division, the law enforcement division, and Director Bonham all took a long, hard look at the language of the law. Pot capacity is the main factor in approving or denying normal Dungeness permit transfers, but the emergency permit transfer provision, they all decided in the end, said nothing about capacity.

There was little the department could do, said Warrington. Unlike most California fisheries, Fish and Game has no direct authority to regulate the Dungeness fishery. "Dungeness crab is one of the last fisheries that the Legislature has maintained control over," he said. The department's role is to enforce the Legislature's laws, and in this case, the law was clear. "Did the Legislature leave out capacity for a reason? We don't know," Warrington said.

Two laws, one already on the books, and one proposed, should tighten the emergency permit provision. Senate Bill 369, passed last year, puts pot limits on the California Dungeness fishery starting in 2013. It outlines seven levels for the roughly 600 permitted boats in California. The 55 boats that caught the most crab between November 2003 and July 2008 are allowed 500 pots; the next group of 55 is allowed 450; then 400; 350, and 300. The rest of the boats that caught more than 5,000 pounds of crab during the five-year period are allowed 250 pots each. Boats that caught less than 5,000 pounds, of which there are more than 150, are deemed "latent" and are allowed just 175 pots.

The pot limit is intended to slow down the ever-escalating crab pot arms race. According to a 2004 study of the Dungeness fishery in California, between 80 and 90 percent of all legal-sized crabs are caught every season. Of those, 80 percent are caught in December, meaning that the first days after the opening are an all-out scramble, with crabbers stacking as many pots on their deck as they can, sometimes more than is safe or prudent.

Warrington said that pot limits will also close the emergency transfer loophole. ("If that's what it is," he added.) Even if a damaged small boat leases its permit to a bigger boat, the number of pots on the permit won't change.

A second bill, AB 2363, currently before the Legislature, would amend the emergency provision, stipulating that emergency permit transfers can be made to boats no more than 10 feet longer than the original vessel. The Wes Chesbro-sponsored bill should make it to the governor's desk without any problems, said Zeke Grader, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen's Associations, which helped design it. "There's been no opposition," Grader said.

But the local crabbers are still griping. That's because there's one thing neither bill can do, and that's stop the situation from repeating next season. Bill 369, the pot limit bill, is scheduled to take effect in March of 2013, or roughly halfway through the season -- after the best crabbing is over. Furthermore, because it will have to step up enforcement, Fish and Game has said that, realistically, it won't have time to print tags and ready the necessary infrastructure until at least the 2013/14 season.

Grader said that he hopes AB 2363 makes it to the governor's desk by January 2013, and would go into effect immediately.

That's not fast enough, the locals say -- it's easy enough to find something wrong with a boat. Like Pellegrini, Rick Shepherd predicted that the tsunami boats will be back next year, and in greater numbers. Shepherd, president of the Del Norte Fisherman's Marketing Association, said, "They're gonna go, ‘My dipstick's broke!' and go to an 80-foot boat."

Mike Cunningham, despite his displeasure over the way his new competition used the emergency transfer provision, was almost forced to use it himself. "We were about 10 days into the season, and I had a major breakdown -- the transmission on my boat went out," he said. "I'd had it rebuilt just a year before. It never should have happened."

The breakdown was costing him thousands, maybe tens of thousands every day. "I started scrambling around, thinking I might have to lease a boat from someone," he said. Luckily, he found a replacement transmission within a couple days, but the experience softened his opinion on the emergency provision. "It caused me to look at it differently," Cunningham said. It's a necessary provision, he said, but it's important that it's only used by people who really need it, not people who hadn't crabbed in years, and simply want to make a buck. "It's a very well-meaning, good provision," he said. "But it was just so badly abused in this case."

Not in his case, said Richard Juneau, owner of the Debi J. Juneau said he spent months after the tsunami trying to find another boat. When Pacific Fishing asked him to lease the permit, he accepted. (Juneau said that he was approached. Hampel maintained that in all cases, the boat owners came to him.)

Fish and Game and lawmakers should leave well enough alone, Juneau said. As a fisherman who caught crab every year, he was exactly the type of person the provision was meant to protect, he said; the law did what it was supposed to. "To tell you the truth, it's sad that these people are gonna try to get that "loophole" out of there. If something happens to your vessel, try to find another one exactly the same size." Not easy, he said.

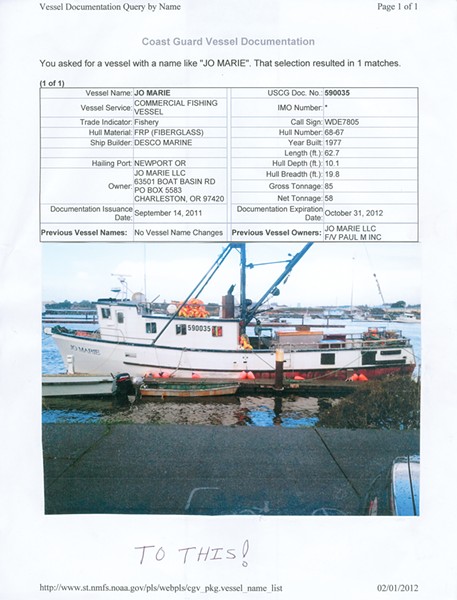

He tried to join the crew of the 62-foot Jo Marie, which fished his permit, but it already had a full crew. He ended up taking the season off, and he's thinking hard about a permanent career change. The new pot limits will probably squeeze him, forcing him to run fewer pots than he had in past years, and the expense of setting up a new boat could be hard to shoulder, he said, sounding dejected. "I'm just driving down the road, shaking my head, thinking, ‘How much longer do I want to stay in this game?'"

It's June now. A worker with a moustache and a hairnet maneuvers a yellow forklift with a stack of crab pots around the parking lot next to Pacific Choice's Eureka processing plant. Inside each pot is a coiled line and floats. He sets them down next to a bigger stack, one of half a dozen orderly piles in the lot.

The tsunami boats are done crabbing, as is most of their competition. Even with the out-of-towners dropping pots, it was a good year for almost everyone. Dungeness crabs were abundant, and they got good prices -- $3-per-pound at the beginning of the season, and almost double that later on.

In retrospect, Harris said he would have fought against allowing the boats to fish in California just because of the disruption they caused, but things would have ended up the same -- the crabbers would just be mad at some other company. "The bottom line is that this is a highly, highly competitive industry," Harris said, and Pacific Choice has plenty of competitors who also knew about the permits. "Somebody woulda got 'em."

As for next season, there are no guarantees Pacific Seafood won't go after whatever permits become available, said fleet manager Hampel. "I don't know what's gonna take place next year."

Warrington at Fish and Game said that if AB 2363 doesn't pass before emergency permit transfer requests start coming in (and per Grader, it probably won't), then the department has no more grounds to refuse the transfers than it did this year.

That's all to say that, minus one tsunami, the situation going into next season is exactly the same as last season.

Comments