Northcoast Journal Mailbox

March 15, 2007

Editor:

I represent the non-governmental defendants in the Mad River Bluff litigation featured in your last cover story and I would like to set the record straight ("Water, dirt and time," March 8). I feel sorry for all of the homeowners affected by the erosion of the Mad River Bluff, and I hope that governmental relief alleviates their problems. However, your story omitted important facts about the litigation filed by Lisa Vandenbosch about which the public should be aware and which, in all fairness to the defendants, should have been included in the article.

The lawsuit alleges that Jill Macdonald represented the sellers, but that is inaccurate. Jill Macdonald represented the buyer - Lisa Vandenbosch. The house was put up for sale by the owners acting without an agent. The advertisement referenced in your article specifically said "for sale by owner."

Jill Macdonald served Vandenbosch quite admirably. She had several professional inspections performed on the property that did not reveal any problems with soil erosion or settling. I find it highly unlikely that there are any such problems now. I suspect that the allegations of soil problems on the property itself, as opposed to on the bluff, result from the governmental agencies trying to have Vandenbosch's case dismissed. I have no doubt that the discovery process will reveal no such problems. In any event, there was no evidence of any such problems when the property was sold.

There is, obviously, a problem with Mad River Bluff erosion, but that erosion is not located on Vandenbosch's property, and she was fully warned about the situation before purchasing the property. Your article does not mention that Vandenbosch has also filed suit against the sellers of the property, alleging that they did not disclose the Mad River Bluff erosion. However, the undisputed evidence will be that they did disclose the bluff erosion in writing in the Real Estate Transfer Disclosure Statement. Consequently, Vandenbosch knew all about the erosion and she chose to take her chances. The Real Estate Transfer Disclosure statement plainly stated: "Due to the proximity of the Mad River, properties to the West have experienced soil erosion." Jill Macdonald also adamantly denies telling Vandenbosch that erosion was not a problem as alleged in your article.

I feel sorry for Vandenbosch and I hope that the government helps her out, as I believe that the costs of natural disasters are best spread out amongst the public via first party insurance or governmental aid so that individuals are not financially ruined. However, Vandenbosch's suit against the private defendants is misguided and unjust.

Andrew Stunich, Eureka

In the wee hours of New Year's Eve Day 2005, a terrible storm ravaged the North Coast. Hurricane-force winds uprooted trees, dismantled power lines and flung debris across roadways, essentially cutting Humboldt County off from the rest of the world. Rain fell in savage torrents, setting off floods and mudslides, and the typically placid Mad River lived up to its name. In the morning hours of this chaotic day, while people lit candles and fired up generators to replace their electricity, the Mad crested at nearly 24 feet - less than a foot above flood level.

The deluge finally let up, and Humboldt's frazzled citizenry stepped out from their dimly-lit bunkers to see the fallout. Homeowners on McKinleyville's Verwer Avenue and Ocean Drive ventured out to find a sizable chunk of their river-front property had been devoured in the night. Fifteen feet of bluff had gone missing, carried out to the ocean and irretrievably lost. Now the homes closest to the bluff's edge stood only 15 feet away. As the stark reality of the situation settled in, with it came a sense of urgency in residents of the neighborhood.

Over a year later, that sense of urgency has only somewhat subsided. Last week, it was announced that a federal agency - the National Resources Conservation Service - had come through with a promise of $1.5 million to shore up the bluffs. Supervisor Jill Geist told the local dailies that the State Office of Emergency Services will likely kick some more cash into the kitty. But the deal is far from done: In return, certain landowners on the bluffs would have to accept responsibility for maintaining the land and agree not to sue the government for further damages to their property. Much about the deal is still unclear, but an agreement must be reached soon if the NRCS's cash is to go to McKinleyville and not elsewhere in the country.

In the meantime, with the last week of heavy rain, still more of the bluffs are crumbling away, bringing the void yet closer to the homes on river's edge. And some are wondering why a more permanent fix to the problem was never pursued.

When Karen Earls first visited Humboldt County,she liked what she saw. It didn't take her long to move from the Bay Area and accept a job at HSU. But Earls wasn't just infatuated with the area -- she was truly smitten, and wanted to put roots down. After making offers on two homes and having no luck, the 58-year-old finally purchased a small, 1,100-square-foot, ranch house at the corner of School Road and Verwer Avenue in McKinleyville. She purchased the home for $240,000 and moved in at the end of June 2002.

While it wasn't first choice, the house did have a feature of particular importance to Earls, and her partner Ward, a college administrator who provides services for disabled students. "We have a lot of close friends who are in wheelchairs and it really meant a lot for us to have a house where we could invite them for dinner," Earls said. "In the former house there was no way, because of the stairs, and here even the bathrooms are wheelchair-accessible. So that was a real selling point."

One day in January, Earls stood on the gravel surface of Verwer Avenue, a private road which she owns a good portion of. She pulled her checkered dark-and-light-green jacket close against the biting wind, and pointed to a small tract of grass in front of her house overlooking the Mad River. "It was a big field, I mean it really was," she said, peering over her bifocals at her land. "And now I don't call it that anymore - I call it a strip. And I used to come out and sit quite often, but I haven't in over a year. It's not so much that I'm afraid, it just makes me feel bad."

A few homes down from Earls lives Lisa Marie Vandenbosch. Though her property isn't directly exposed to erosion at the moment, like that of Earls', she grew tired of waiting for the government to act and decided to light a fire. In December, Vandenbosch, with the help of Eureka attorney Bradford Floyd, formally filed a lawsuit against the county, Caltrans, Cutten Realty and its agent, Jill Macdonald. The suit claims that these parties played a role in either increasing, or not making Vandenbosch aware of, the potential for erosion on her property, and seeks payment of more than $25,000 for depreciated property value and mental distress.

Though both Vandenbosch and Floyd declined to speak about the case, a look at the lawsuit reveals that on April 30, 2004, Vandenbosch closed escrow on the home for $357,000. An ad for the property had caught her eye: "FSBO, 3BD/2BA remodeled home on private road, 1566 sf on 1/4 acre with panoramic ocean view and view of the sand dunes. Listen to the ocean and enjoy incredible sunsets in this newly remodeled home on the banks of the Mad River ..." In late March 2004, Vandenbosch hired an agent - Macdonald - and made an offer on the home.

In the suit, Vandenbosch alleges the real estate transfer disclosure statement, prepared by the sellers and required by law for any such transaction, purposely misled her before she bought the home. "The disclosure statement specifically denied the property was experiencing any known problems due to settling, sliding, or other soil problems," it reads. The document also claims Macdonald, in her capacity as Vandenbosch's agent, expressly told her she didn't think erosion was a problem on the property. (Macdonald also declined to speak about the case.)

As for the charges against the county and Caltrans, Vandenbosch alleges that a 1970 armoring of the south bank of the Mad River, a bit upstream from her home, altered the course of the water toward the Mad River bluffs causing the erosion. The armoring of the bank was done to protect Tyee City and the road to Mad River Beach. Tyee City is the seemingly deserted conglomeration of run-down looking structures, next to the road and just before the beach. In addition, Vandenbosch claims the boat ramp at Mad River County Park, also built in 1970, diverted the river's course toward the bluffs near her home as well. The suit names "Caltrans and/or County" as the parties responsible for these structures.

For the third contributing factor to erosion of the bluffs, Vandenbosch places blame squarely on Caltrans' failure to act. The suit says that a rock slope protection (armoring) Caltrans constructed in early 1992 below Vista Point, to protect Highway 101 North from the migrating river, along with the work at Tyee City and the boat ramp, led to the erosion of the Mad River bluffs near School Road.

"Caltrans was aware that construction of the RSP on the north bank of the [mouth] of the Mad River, along with the Tyee City RSP and boat ramp may destabilize the Mad River bluffs," the document reads.

The county has rejected the lawsuit but representatives from the courts weren't sure when the case would go to trial. Meanwhile, Caltrans public relations officer Ann-Marie Jones would only say of the suit, "No comment at this time. We're in the process of discovery and that could take several months."~~~

The Mad River hasn't been pristinesince Lord knows when. It's been managed, channelized, diked, diverted and gravel-mined for industrial use since settlers first came in the 1800s and started chopping the giant trees down. They'd use the river to float the logs down through the watershed, and they cut channels in its banks to get the wood into Humboldt Bay for transport.

Geological records indicate the mouth of the Mad River flowed into Humboldt Bay only 500 to 800 years ago. It now flows several exits to the north, and is positioned just south of Murray Road in McKinleyville. What factors have driven this migration?

According to a 1992 report by a Caltrans hydrologist Rahim Kia, who was given the task of figuring out why the river migrated all the way north to Clam Beach in the early '90s, there are three main factors influencing the movement: river floods, ocean waves and the sand-transporting wind. When the river is at high flood levels, it wants to cut a straight and direct channel to the ocean, Kia writes. However, wind and tides coming from the southwest are constantly pushing the mouth north by depositing sand into it. This northward trend continues until a major flood event or wave attack from the ocean cuts through and opens up another mouth to the south. The river then chooses to flow out of the southern mouth because it's the most direct, and least resistant, path to the ocean.

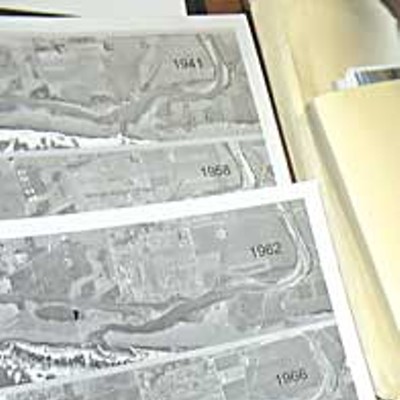

This constant migration takes its toll on the land around the river's final stretch - particularly the bluffs that line the east bank of the Mad around McKinleyville. In the mid-'90s, Caltrans hired Jeff Borgeld, an HSU oceanography professor, to study how the transportation agency's slope protection project near Vista Point (just south of Clam Beach) might affect the river's course. On a January afternoon, the mustachioed Borgeld opened his office doors after class to welcome a reporter seeking his expertise on the subject.

Borgeld said the oddest time period for the Mad River mouth's migration occurred from the mid-1970s to the late 1980s, when the river never jumped south as it typically did (fluctuating between Hiller and School Roads), but kept migrating north to where Vista Point is. "Then they built the rock slope protection to halt the northward migration, and not too much later we had an El Niño event," he said.

During El Niño years, pressure on the ocean drops, leading to higher sea levels and bigger waves, the professor said. El Niños also bring increased rainfall to the North Coast, which in turn increases the intensity of river flows. In this particular El Niño event (1997-1998), "three mouths actually opened up, and the Mad chose the southernmost one and jumped all the way south. The two northern ones filled in, and that's where we are today." As to the question of whether the Caltrans slope protection at Vista Point caused this southward retreat, and consequently erosion at the bluffs, Borgeld responded: "I can't imagine how. The river has done very similar things to that in the past and at the time that major erosion happened the rock slope protection up by Vista Point was literally high and dry. The river wasn't anywhere near it."

The report by the Caltrans' hydrologist, Kia, identifies a factor unnamed in the Vandenbosch lawsuit as the primary reason for the Mad River's northern migration and resultant erosion on its eastern edge - the destruction of the Sweasey Dam in the summer of 1970. Formerly located just upriver from Blue Lake, the City of Eureka used the dam for water supply. But with the construction of the Ruth Dam higher up the Mad's watershed in southwestern Trinity County, the Sweasey became obsolete, and was abruptly removed. The dam was demolished using dynamite. "[Five and a half] million tons of beach material was washed out of the reservoir and delivered to the river's mouth," Kia reports. The sediment equaled roughly 15 times the normal river sand supply, increased the impact of sand deposited by wave and wind action into the mouth from the southwest, and thereby accelerated the mouth's migration to the north.

For Tom Marking, general manager of the McKinleyville Community Services District, the main reason the river is now cutting away the bluffs beneath the homes is a peninsula that's come into being within the last five years. A few yards north of the boat ramp, the river is forced into an eastern curve by the patch of accumulated sediment now housing a growth of dreary vegetation. Karen Earls describes it like this: "It's grown a lot over the last few years and there's European beach grass down there. Before the introduction of this plant the sand would build up in the summer and get washed down, and that's not happening anymore, it just stays."

If the recommendations of theCaltrans hydrologist had been followed, this bend wouldn't exist today, and Vandenbosch's lawsuit would likely have never been filed. But the course of inaction is always least resistant, and even after this foreboding summary report from Kia nothing happened: "If we let the channel continue to march north, or we stop the inlet [mouth] channel at its existing location, (near Vista Point), the inlet channel has a good likelihood of attacking the properties on its left bank [i.e. the Mad River bluffs] "

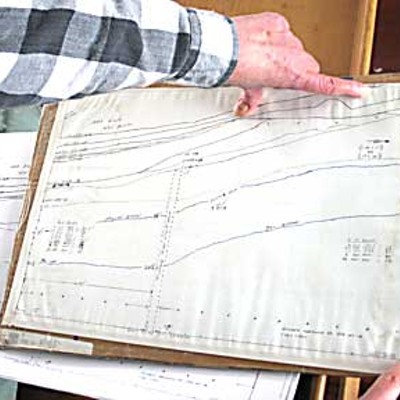

What did Kia recommend Caltrans do about it? Bob Busch, founder of Busch Geotechnical Consultants, has always been of a like mind.

"What they should have done was taken a couple of [bulldozers] and gone right through to the ocean," Busch explains. "Number one, historically the river's gone out there. Number two, because those in power allowed the river to keep meandering north, cutting, we lost some Ice Age sand dunes. Because the river just kept going north toward Clam Beach and turning and always cutting on the outside of the meander, and it just cut north like you were slicing pieces of cake and by the time Caltrans came along and put in all that rock and grind system all that dune had been lost.

In his 22 years of business, Busch has done plenty of consulting in the Mad River bluffs area. The most substantial work he's done there was for the MCSD around 10 years ago, studying a site where the district was looking to place a leach field. Even then, Busch knew the bluffs, if not protected, could spell trouble for area property owners. "We actually suggested they stabilize the bluff and protect it because even then, in the mid-'90s, we could see the river was basically trying to erode the toe of the area they were using," he says. He believes the reason nothing was done is related to the existence of a certain population who wouldn't want concrete buttressing in the river, and the huge expense of the undertaking.

Busch never mentions the Kia document, but what he names as the proper solution to save the bluffs from eroding could have been taken right out of that report. In the summary to his study, Kia states: "The most appropriate way of protecting Highway 101 is to return the Mad River tidal inlet [the mouth] to its historic location near School Road. This can easily be accomplished by cutting a 50 foot wide channel through the area of the historic river inlet." Kia's report also advises placing flow deflectors or rock slope protections exactly where the erosion of Mad River bluffs is occurring today. But that was nearly 15 years ago, and hindsight is 20/20.

Right now, it looks like the onlysolution on the table is the one being offered by the National Resources Conservation Service. It's still unclear to everyone involved precisely how that agency's $1.5 million capital infusion would be spent in shoring up the bluffs, but it is certain to involve some sort of hill-stabilizing measures - "armoring the bank," as was done upstream at Tyee City.

Karen Earls, one of the property owners being asked to sign off on the deal, is still uncertain. In the first place, the offer would likely require some sort of cash infusion on her behalf - to share the cost in applying for the permits to buttress the crumbling hillside in her backyard. She'd have to accept responsibility for maintaining the buttress. Then, she would be required to sign a paper in which she would indemnify the government - to give up all rights to sue, as her neighbor Lisa Marie Vandenbosch has done, either to recoup further losses or to force a permanent fix.

Earls didn't sound in the suing mood last week - she had nothing but praise for Supervisor Jill Geist and MCSD General Manager Tom Marking, who she said had worked very hard to find funding. But she was still uncertain whether or not she could sign off on the proposed deal.

"First of all, I don't know exactly what it is," she said. "They gave me some sample contracts. I'm trying to evaluate whether I have the ability to do it. Basically, it's an undefined project - so I'm supposed to sign it and take responsibility for it, but I'm not sure what it is."

Still, she acknowledged that she seemed to be out of options. The NRCS has made it clear that its offer will certainly expire if it is not accepted soon; other, possibly more threatening, emergencies could arise at any time, somewhere in the nation, and when they do the service may have to shift its funds in response. Also, the only possible time to do the work is in the summer and the fall, when the river is running at its lowest, and there'll be a mountain of paperwork to get through before then.

"It is frustrating," Earls said.

Meanwhile, calls to neighbors confirm that bits and pieces of the hillside, swollen by recent rains, are still falling down into the river, which buffets the base of the hill mercilessly. More than one clock is ticking.

Comments