On Oct. 28, a dense fog poured into the towns around Humboldt Bay, stuffing the spaces between buildings with a white, impenetrable ground-to-sky murk. You couldn't see 10 feet in front of you, and if you happened to be out on the Samoa Peninsula and stopped your car just across from where the Evergreen pulp mill ought to be, you could imagine it wasn't there. Just whiteness. It was as if the once-dependable white steam plumes -- Eureka's weathervane -- that had waved from the mill up until the week before, when the mill shut down, had returned with a ghostly, spreading vengeance to haunt us all.

Actually, things around the mill had been pretty murky for weeks. Months. Ever since the stock market took its first big nosedive and the stock of the company that owned Evergreen, Lee & Man Paper Manufacturing Ltd., went with it. Credit had frozen, people weren't buying stuff, demand for containerboard -- one of Lee & Man's main products -- plummeted, and there went the price of pulp. Energy, freight and chemical costs, meanwhile, had skyrocketed over the past year and a half, said Rex Bohn, who was Evergreen's vice president of resource management until his job ended two weeks ago.

Some vendors filed mechanic's liens against Evergreen for bills unpaid. Wood chip deliveries slowed, then stopped -- from 125 truckloads a day to zero.

In early October, the company announced the mill would shut for a couple of days. Then they said it would be a little longer, and 15 percent of the workforce would be permanently laid off. The story kept changing, said several workers interviewed last week, management grew quiet, and the place became a rumor mill.

Finally the company announced that the mill would close -- for three to six months, maybe, whenever the market recovered -- and everybody would be laid off.

Then news broke that Lee & Man had actually sold Evergreen to an outfit incorporated in the Virgin Islands called Worthy Pick. Evergreen CEO David Tsang (who didn't return the Journal's emails or calls last week) later told the Times-Standard that it was just a restructuring, a way to refinance the mill so it wouldn't go bankrupt.

The mill stopped production Oct. 15. By the end of last week, only about 20 employees remained to keep the place "warm" -- some to guard the place, others to keep the effluent line out to the ocean flushed clear of silt.

And the rest? What will they do?

We talked to a handful of pulp employees, including some who've been there since the mill opened in 1965, about their lives at the mill and what comes next.

Midmorning two Fridays ago, in a Eureka neighborhood, Brian Connors' son, Paul, grappled with the underside of his fiancee's sister's old Chevy. It needed a new brake line. Paul, 22, was home for a wedding: He's a military helicopter pilot based in Germany, he just finished a 15-month tour in Iraq, and now he and Maggie -- his girl next door -- were getting married in a week. Maggie watched the car operation from the sidewalk with her sister and mom.

Connors said hi to them then walked through the house into the back yard and sat at a picnic table. The yard was tidy, flanked on one side by a sturdy fence Connors rebuilt after he moved into the rental eight years ago, and on the other by a fence laced with scraps of ivy -- you could see where other ivy tentacles had been pried loose and torn off. "I call it the Great Ivy Project," said Connors. He pointed out the blackened pit in the ground where he and his granddaughter recently burned some of the villainous vegetation.

Connors, 50, is a Fortuna High grad -- his family moved up from Los Angeles in 1968 after the riots. He describes himself as a conservative Democrat: "Pro-choice, pro-gun. Fiscal conservative."

After high school he went into the Army for a brief stint; then he served in the California Army National Guard for 22 years. He worked a variety of jobs until he landed at Pacific Lumber Co. in 1988, in the shipping department. "It was something I said I would never do, be a mill worker. But it was good money."

Eighteen years later, in December 2006, he lost that job in one of PL's rounds of layoffs. He was one of the workers promised a severance package that never materialized after the company filed for bankruptcy.

"I was very relieved it was over," said Connors. "We had been going through 10 years of hell down there at Palco, layoff after layoff, uncertainty after uncertainty, broken promises by the company and the government. ... It was almost like the ending of a real bad marriage. Once it was over, I could move forward."

He went to the county's employment training division, which administers federal funds to help displaced workers retrain or become re-employed. He thought he'd become a surgical technologist, but the school was in Sacramento and the federal funds covered tuition and books but not living expenses. And -- his pet peeve -- he couldn't, as an individual, access any of the Headwaters Fund, presumably intended to help displaced timber workers.

A few months later, he got a job at the Evergreen Pulp mill.

First they put him on yard labor -- pick up the trash, shovel this, paint that, move these -- and then he went into the bleach plant. "My first job there was to screen the pulp, to take the wet pulp and take the rocks and the shives out of it." Shives are slivers and knots. He also worked in the control room. "I sat in a small little office with buttons and dials and a computer screen, and pushed buttons. ...They liked it when your feet were up on the desk and you were reading a magazine. All was well."

It paid well, too: $21.43 an hour, plus overtime and good health insurance.

But the sweet gig didn't last.

"This [layoff] has gotten to me," Connors said. "But I'm not sure who to be mad at. It's really kind of odd. There's no boogeyman. There's no Charles Hurwitz. I understand Evergreen's position. I understand the world market. It sucks right now, it's really bad. When I was in Germany last week [a long-planned vacation to visit his son], I saw it there. People were laid off, things were slow. It's not just us."

Connors is going to wait to see if the mill starts back up. "I want to go back to Evergreen. I liked working for Evergreen. For someone in my station of life, it was good for me. It paid well, it was local. I don't want to start someplace new. I don't want to do it."

He's not worrying, he said, but he really doesn't know what he'll do if the mill doesn't reopen. "It's becoming really hard here for the high school graduate homeboy to make a living," he said. "It really is. When my father came here in 1968, there were 6,000 jobs on that peninsula. Two pulp mills. You quit one mill and you could go work for the other mill the next day."

But for now he had a wedding to celebrate. And there was always the Great Ivy Project. Although he's already about licked that.

Jeff Clark sat in a booth at Adel's in Eureka two Mondays ago, sipping coffee. If he were working, he'd have ordered breakfast. But he's been on disability since summer -- a twisted knee from February, complicated by a labyrinthine, months-swallowing nightmare of insurance agents and doctor's orders. So, these days, he'll just have a light lunch and then "drink milkshakes all afternoon -- Häagen-Dazs raspberry chocolate swirl."

Clark laughed boyishly at this admission. But he seemed an otherwise serious guy -- a big man, watchful eyes penetrating glasses above a brushy gray mustache, wearing a no-bull workingman's wardrobe: ballcap with a stars-and flags pattern, black T-shirt with a bald eagle silkscreened to it, and sawdust-colored canvas work jacket.

Clark lived in Korbel till he was 5 -- his dad was a powder monkey for Hammond Lumber Co.; his mom was a nurse. Then his family moved to Eureka. After he graduated from Eureka High, in 1964, he was drafted and sent to Vietnam.

"Got out of the Army in ’67, came home, and CR was having physicals for their very first football team," he said. So he got on the football team. But it wasn't right.

"It was like everybody from high school was out there for football, all the guys I played with in high school," he said. "And after being in the Army, and I was 21 years old, I thought, wow, there's a bunch of little kids around here. Nobody's been shot at, and, you know. And after football season, I kind of became disillusioned."

One day a friend asked him to deliver some wrist braces for the people working greenchain at Georgia Pacific's redwood mill. "And I took ’em out there and the guy says, you want a job? And I said, sure. And I walked down the hall and I asked when do I start. So I went to work there, at the pulp mill."

It was 1968. Georgia Pacific still owned the plant, which it had opened in 1965. There, World War Two vets mingled with young Vietnam vets plus a host of management types imported from Canada. Clark started in the bleach plant, at the bottom. "It was basically as a tester -- you would get samples [of pulp] from the process and you would run titrations."

He was paid $2.60 an hour. (Forty years later, he was up to $26-plus an hour.)

That first day on the job, he also was handed an armload of blueprints by the shift supervisor. "He said, 'Here's the prints for the bleach plant,'" said Clark. "And this is a three-story-tall building with 500-something pumps and pipes and valves and everything. And he said, 'Now, take your time, here's the prints, and I expect you to learn every valve, every pump.' And, you know, it was mindboggling." He loved it.

Back then, he said, the mill took redwood and Douglas fir -- species with the longest fibers -- and turned them into pulp for high quality book paper, using chlorine gas to bleach it. (The mill later quit using toxic chlorine.)

"In the early days there were a lot of spills and overflows and every once in a while a chlorine leak," said Clark. "One time we had a chlorine line about this big around [he made a fingertips-touching circle with his hands] outside the control room, and all of a sudden there was this big bang and kind of a yellow cloud comes into the control room. And of course everybody has their escape masks, so I put my mask on. So, we go out and isolate the line, and our rallying point was in the breakroom in the main building. No problem. It only took a couple of minutes. But we were all down there in the breakroom, and somebody said, well, we might as well have a cup of coffee, and I reached in my pocket, and all my money had turned green and stuck to itself."

Rather than be an operator in the plant -- the guy running the machine -- Clark really wanted to be a millwright -- the guy who fixes the machine. In 1975 he earned an apprenticeship.

"I started in the millwright shop on Jan. 27, my daughter was born on the 28th, and my mother's birthday was on the 29th. That was a good week!"

Clark pulled out a worn, leather wallet and tugged at its innards until two time-nibbled cards broke free. "Draft card from '64, and journeyman card -- that's the card from my apprenticeship," he said.

Clark's had offers from people to come work for them. He's thought about retraining. But he'll wait to see if the mill reopens -- despite his suspicion that from now on Lee & Man's going to just get its pulp from its new pulp mill in China; despite the disability tangle; despite, even, a communication style among Evergreen bosses that he characterized as "do this -- no discussion."

Clark's 62 and wasn't planning to retire until he was 70. Besides, he loves the machine.

Last Thursday afternoon, a day before Halloween, Tommy Lawler was at home in McKinleyville. Since his last day at the pulp mill, Oct. 17, it's been his job to look after the home: clean, cook, do the laundry. The electric jack o' lanterns and ghosts were at the ready, lining the walkway to the front door of the nice suburban home he and his wife bought last year. His wife was at work -- she recently landed a great job with the county as a school nurse.

Lawler, meanwhile, was still dealing with the fact he'd lost his great job. A Humboldt State grad in journalism, Lawler, who's 31, started at the mill in December 2005. Lee & Man was about to buy it from the financially strapped Stockton Pacific Enterprises -- which had bought it from Samoa Pacific Cellulose in 2003, which in turn had bought it in 2001 from Louisiana Pacific, which had it since 1972 when L-P spun off from Georgia Pacific. The mill was plagued with environmental violations. Its crew had been slashed to skeletal. It owed money to the water district.

Lawler heard good things about Lee & Man -- it had money to turn things around.

"At first they put me in the recaust department -- it's where they make their white liquor. You need white liquor to break down the chips. So it's where the lime kiln is. It's the grubby part of the mill."

Then he became an operator. But he was really interested in electronics, and he knew a fair bit about computers. So when he heard the mill's new owners were going to re-start the maintenance apprenticeship program, he applied. He got it, and a year ago started on the four-year program to earn his state certification as a journeyman in instrumentation. With that, he'd be able to get a job anywhere.

"I wanted a job I could work until I was old, and not kill myself [physically]," he said. "I have a guy in my shop who's 70 years old and a guy who's 62."

The apprenticeship paid for online college classes and books, and $20 an hour during his training. Once he made journeyman, he'd make $27 an hour.

"Unfortunately, I only had a year [of the apprenticeship]," he said. Then everybody got laid off. He can continue studying online -- the books and classes are paid for. But all of that's useless without the hours of required hands-on work experience.

"I've kind of lost motivation," he said. "Over the last month, with all the doom and gloom, I'm not really that into my books."

Still, he's not as bad off as a coworker buddy of his, who can't pay his bills on unemployment, and who had to move his wife and two kids into his wife's parents' home recently.

Lawler said he and his wife were planning to start a family -- and they don't want to stall those plans.

He doesn't know what he'll do. Go back to school. Move -- neither he nor his wife wants to do that. Compete with the dozens of good workers from the mill with 20 to 30 years experience on him for the few good local jobs.

For the moment, he's resting. Keeping house. Working out. Studying a little.

"The main thing is just getting happy again," he said.

Glenn Vickers -- 63, a tall man with a white Fu Manchu mustache, dressed in jeans, brown workboots and a sweatshirt -- sat on the back steps of his house in Manila last Wednesday afternoon, next to a play area filled with bright-colored plastic playground equipment. The ocean crashed, just a pile of dunes away. Inside the house, his wife, Wanda, tended to several of the children who come to her daycare, and while it was apparent Vickers is fond of the kids, and they of him, he said he couldn't deal with such commotion all day long. "That'll drive you nuts."

That's why he works outside, he said goodnaturedly. Lately, he's been digging up the sizeable front lawn, currently atop water-sucking sand, so he can put in topsoil and plant new lawn. And before the mill shut, well, he was at work most of the time -- a condition he enjoyed.

"All I've ever done is work," he said. "I started in August of 1963 with Georgia Pacific, in the lumber end. There was a whole bunch of people working there in 1963. They still had the train coming down out of Crannell [the tracks run past his house] -- Hammond Lumber Co. had their own set of railroad tracks, and in the old days they were logging old-growth redwood out of Crannell, that area up there."

Vickers grew up in Manila; both his dad and stepdad worked in the timber industry. He got on with GP's sawmill when he was 18, fresh out of Arcata High.

"It was easy to get a job in those days," he said. "It's not like it is today. I mean, I started right off making the same wages that a man would make to support a family."

First he was a spotter for the forklift driver -- helping line up the load. Then the company, noticing how good his high school grades had been, moved him to the storeroom that serviced all of GP's mills -- including a sawmill, stud mill, plywood plant and, later, the new pulp mill.

He eventually became manager of the storeroom, and that's where he's been ever since, not counting the 13 months he served in Vietnam, nor the 13 months total he figures he spent on the picket line over the decades, nor other shutdowns including eight months the mill was closed in the mid-’90s. "My plan was to work for a little bit and then go back to college," Vickers said. "But I was making really good money. And once you get in... ."

In 1965, GP had "2,000 people working from the bridges that cross the bay down to where the pulp mill is," Vickers said. "Every day was abuzz."

The peninsula was the county's Iron Belt. Now there's just the pulp mill and, farther south, Fairhaven Power, a wood-fired power plant. The other pulp mill that was built on the peninsula, in 1966, and run by Simpson, closed in 1990 -- there weren't enough wood chips to supply two mills anymore, and required pollution upgrades were too expensive, said Vickers. So, while his mill spent the $66 million for a state-of-the-art recovery boiler, Simpson's mill just shut down.

"That was the biggest culture shock that I have ever experienced, as far as workers," said Vickers. "Because, they made more money per hour than we did. There was 200-some of them, making well over $50,000 even then, and all of a sudden they're making minimum wage. One of ’em, I know of, took a job as a tow truck driver. Some of ’em retired. Some of the salary people, with skills like purchasing and engineering, went to other mills. A few of ’em came to [our] mill."

Vickers' storeroom was bigger than Gottschalks. He purchased and distributed everything the mill needed to keep running -- toilet paper, bolts, motors, gearboxes, machines, you name it; everything but the chips and logs, which were handled through another department.

"I think the pulp mill is absolutely a good thing for Humboldt County," he said. "When they're fully running, they pump about 70 million bucks into the local economy -- that's payroll, buying chips, paying vendors. There's over 200 people working there, and everybody's making well over $50,000 a year -- it's a living wage. They buy locally -- they buy automobiles, they go out to dinner. Evergreen always stressed buying locally if you could. Even if the local vendor was a little higher than the guy out of town, we still bought locally."

Vickers has signed up for unemployment. He might retire -- his insurance would still cover him to 65.

But even if he does, if the mill fires back up it'll need him for a bit. He's the guy who set up the computer system in purchasing ages ago -- and he has the code to get in.

The heavy fog last week only lasted a day or so. Then a storm blew in, wind and rain. Early Friday morning, the pulp mill's white buildings shone in stark relief against the night-blue sky. A light sparkled from one corner. No steam plumes, of course. But the machine looked alive.

Evergreen employee Richard Marks, president of the Association of Western Pulp and Paper Workers Local 49, said he's seen signs of good intentions from the company. It's going to install concrete ramps in the chip dump, for one, he heard -- trucks would haul away the old ramps, which were really just compacted piles of woodchips, a costly waste of product. The new ramps, Marks heard CEO Tsang say, will save the company millions.

The company also cleaned out the mill's tanks and hauled away the chemicals. Sam Wong, Evergreen's purchasing manager and, now, spokesperson, said Friday that unlike previous owners who shut down the mill cold, leaving chemicals behind to go bad and muck up the machine, Evergreen "has done a proper shutdown of the mill, so that when we do restart it will be with minimal problems."

Wong had little news on the financial front, however.

The pulp mill is the last of the big mill operations that once dominated the peninsula. More than 40 of its workers have been there over 30 years. The Greater Eureka Chamber of Commerce named it 2007 Business of the Year. As a major Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District customer, and its only industrial user, the mill subsidizes the entire water system -- without it, rates could rise. In the three years since they bought the mill, the new owners have put in millions of dollars in upgrades to solve pollution and other problems. They recruited younger workers, started a scholarship program, revived the apprenticeship program. They were even getting ready to buy another pulp mill, in Washington.

In a county that's seen the mainstays of its timber industry collapse one after the other, the Evergreen mill seemed like a lone stalwart from the past that was actually successfully striding into the future.

And maybe it will make it. But nobody really knows -- not even the head honchos, apparently. It all depends on the world.

•

Finding a niche

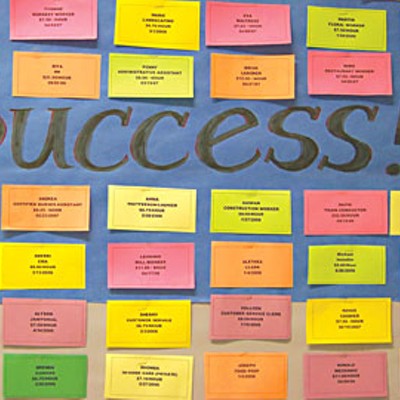

Joe Davey, manager of the county's Employment Training Division, says that 30 Evergreen workers have already come in to start the retraining/re-employment process. The ETD administers federal funds to help laid-off workers. Davey said it was the biggest initial surge he's seen after a mass layoff, and he expects yet more will come in.

Last week, David Corral was there, talking to vocational counselor Tom Deffenderfer. Corral, 45 and an Arcata native, was an instrument technician apprentice at Evergreen for two and a half years. Before that, he worked at Calgon -- the carbon plant in Blue Lake -- until it shut down. He's not waiting on Evergreen, he said.

The subject of a county report on the region's "targets of opportunity" came up -- six areas in the labor market that are growing: diversified health care; building and systems construction and maintenance; specialty agriculture, food and beverages; investment support services; management and innovation services and niche manufacturing. Small-business stuff.

Corral said all that was fine, but he had just taken a look at the list of the more plentiful job openings in the North Coast region. "Most of those jobs are half of what we make at the mill," he said. "Unless you're a nurse, which is a $30-an-hour job. A lot of the jobs in this area are in the $10-an-hour range."

He said he might have to move away for work. "But that's last choice. I have a lot of ties here -- I have a lot of family here and a lot of extended family. I still have two kids in high school."

Comments (5)

Showing 1-5 of 5