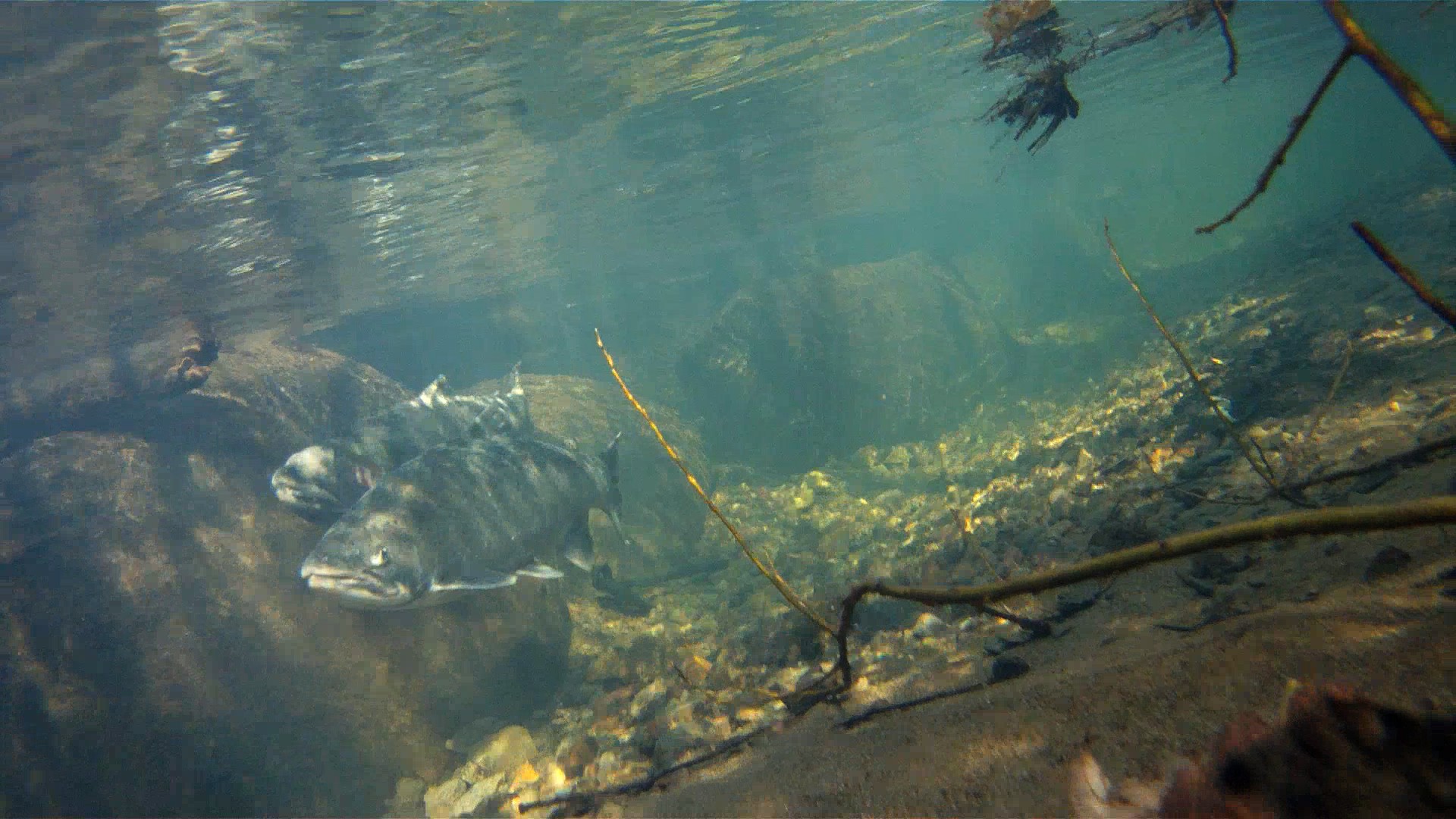

- Photo courtesy of NOAA Fisheries

- Coho salmon

It was June 24, 2008, and lightning fires were raging in the southern Humboldt hills. Then came 450 law enforcement agents — federal, state and local — in some 200 vehicles busting onto the smoky scene.

You remember Operation Southern Sweep, right? No? Well, a brief recap: The officers weren't there to help douse the fires. They were there for Buddha — Robert "Buddha" Juan — and his band of homesteaders who'd bought shares in his Lost Paradise Land Corp. and begun building roads, plunking down structures and, in many cases, planting pot gardens in the gated subdivision called Buddhaville on some 2,000 rugged acres of former timberland straddling Humboldt and Mendocino counties. For two years agents from the California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the IRS, the U.S. Postal Service and other entities had been investigating what they thought to be an illicit, large-scale pot growing and distribution business led by Juan.

The personnel-intensive sweep, which included a few houses in other local communities, yielded what locals considered a piddling amount of pot (around 10,000 plants) cash ($160,000) and firearms (30). Of the 40-some residents of Buddhaville, 10 were federally charged with growing a bit of pot, and received generally light sentences. Juan got five years in the pen for growing and for buying the land with a money order from the U.S. Postal Service.

But what happened to the land? It's come almost full circle, in a sense.

After the sweep, the feds seized it through forfeiture. The booted-off homesteaders lost, collectively, as much as $1 million in down payments, monthly rents and work they'd put into the land, Juan told the Los Angeles Times in 2011.

After a few years, the previous owners of these properties — Bob Barnum Sr. and the Mendes family — to whom Juan still owed money, were given back their respective parcels. About two years ago, the Sanctuary Forest Land Trust convinced New Island Capital, a San Francisco "green investment" firm, to form a company called Lost Coast Forestlands LLC to go in and buy up former timberlands in the Mattole and South Fork Eel watersheds. The land trust would then seek a grant to pay the new landowner for conservation easements. The idea, says Noah Levy, the land trust's lands program director, was to make it possible for these lands to remain timberlands (with strict conservation restrictions), at a time when timber had become less lucrative than development.

Lost Coast Forestlands' purchases included nearly 1,700 acres of the former Buddhaville. And last week, the California Wildlife Conservation Board voted to allocate $3.2 million to purchase easements from Lost Coast Forestlands LLC, which include the Buddhaville property and others embracing the headwaters of Indian Creek, a major tributary to the coho salmon-vital South Fork Eel River, and the Mattole River.

The trust found the Buddhaville development "really worrisome," says Levy, and had tried to buy the property or an easement from Juan long before it was raided.

"It was unpermitted development, often temporary development," he says. "There were people living in trailers, often, and there were [50 or more] sites developed for outdoor marijuana. They were diverting fair amounts of water from those creeks, and from springs that feed those creeks. They were driving back and forth on poorly constructed roads, sometimes right in creeks. There was a risk of much worse things than dirt washing into the creeks, though to our great relief we found close to zero evidence of any toxic or harmful substances having been spilled and no evidence whatsoever of rodenticide or of indoor grows using diesel indoor lights."

Much of the land's been cleaned up, some by Barnum, who fixed roads and removed some of the "huge trash piles, broken greenhouses, degraded cheap cabins and trailers," says Levy.

The easement requires the new landowner to harvest incrementally over a 30-year time frame, widens buffers around creeks and other water sources and protects some mature stands and the few remaining old-growth. The landowner's resident caretaker, and the land trust, will keep an eye on things. And the trees will grow and, the hope is, the land will recover.

Comments