When Napoleon Bonaparte set his sights on clearing the British out of Egypt in 1798, he took with him 160 savants in his 400-ship invasion fleet. These worthies were scientists, artists and historians who, supposedly, would bring the lost civilization of the Egyptian pharaohs to light, thus ensuring Napoleon's legacy not only as a conqueror, but as a scholar and a gentleman. Which is how the so-called Rosetta Stone came to be preserved. In July of 1799, workers rebuilding a fort at present-day Rashid (near Alexandria) happened upon a heavy chunk of granite-like granodiorite. Seeing its inscribed polished face, savant-on-the-spot Pierre-François Bouchard realized it might be of value to linguists and philologists.

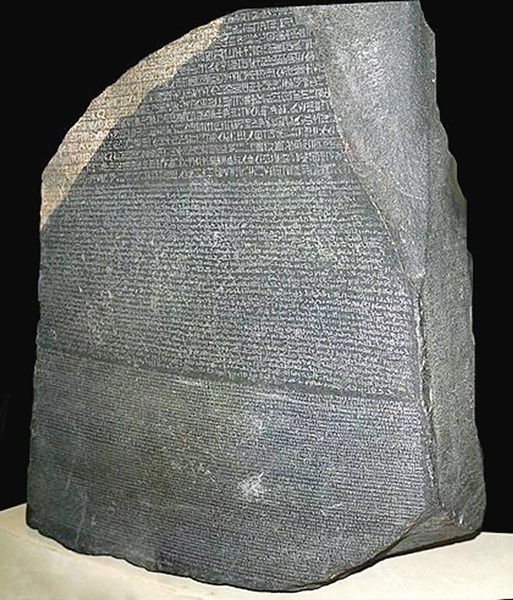

Two years later, the 1,700-pound stone was installed in a custom-built wing in London's British Museum. Why not Paris? Because after British admiral Horatio Nelson destroyed the French fleet, the Brits claimed the stone as a spoil of war (the Egyptians not being consulted). Why the fuss over a 4-foot-high slab of stone? Because even a cursory glance shows that it's inscribed in not one, but three, styles of writing: hieroglyphics (the "lost" Egyptian priestly writing, not used since the Roman emperor Theodosius outlawed pagan worship at the end of the 4th century), demotic (a "shorthand" version of hieroglyphic script, also lost) and ancient Greek (well known and understood by linguistics then and now).

Bouchard was probably the first to realize the Rosetta stone might be the key to recovering the lost languages of Egypt. Once it had been installed in the British Museum, copies (both plaster and "rubbings") were sent to centers of learning in Europe and to Philadelphia, where amateur and professional philologists gave it their best shot at matching the unknown hieroglyphic and demotic writing with the Greek; they knew the texts did match because the Greek text said so. It took another 20 years to figure it out, at which time — suddenly — the thousands upon thousands of hieroglyphics on ancient Egyptian temples and tombs, walls and columns, were readable, shining a light on a great civilization previously known only from its architectural wonders.

Two interpreters did the heavy lifting. Thomas Young was an English physician and gentleman-scientist who made the original breakthrough, realizing the stone's "cartouches" (oval-shaped enclosures in the text naming non-Egyptian rulers) were phonetic. Frenchman Jean-François Champollion, 17 years Young's junior, was a brilliant linguist who had learned, among many other languages, Coptic, which descended from Ancient Egyptian and is still used by the Egyptian Orthodox Church. Champollion ran with Young's cartouche interpretations but that turned out to be just the start in deciphering the complex hieroglyphics. After five years' intense work, he wrote that the script was "at the same time figurative, symbolic and phonetic, in one and the same text [and even] in the same word." No wonder it took so long! (Young and Champollion died early, at 55 and 41, respectively, both as honored scientists.)

The text of the Rosetta Stone itself — which reappeared in at least three other stelae subsequently found — is comparatively uninteresting. Originally set up in 196 B.C. in a nearby temple, the stone celebrates the coronation of the Pharaoh Ptolemy V, "... who has secured Egypt and made it prosper ... who has enriched the lives of his people ... the god manifest whose beneficence is perfect." It wasn't the text itself, but the opportunity the stone gave to linguists, and hence to historians, that makes the Rosetta Stone so valuable and, incidentally, the most visited object in the vast British Museum collection.

It's also one of the most controversial pieces: Why shouldn't it be returned to its country of origin? Egyptian archaeologists want to know. Like the Elgin Marbles (saved/stolen from Greece in the early 1800s), the story of the Rosetta Stone is unfinished.

Barry Evans (he/him, [email protected]) always makes Room No. 4 of the British Museum his first stop on his near annual pilgrimage there, where he pays due obeisance to the topic of this column.

Comments