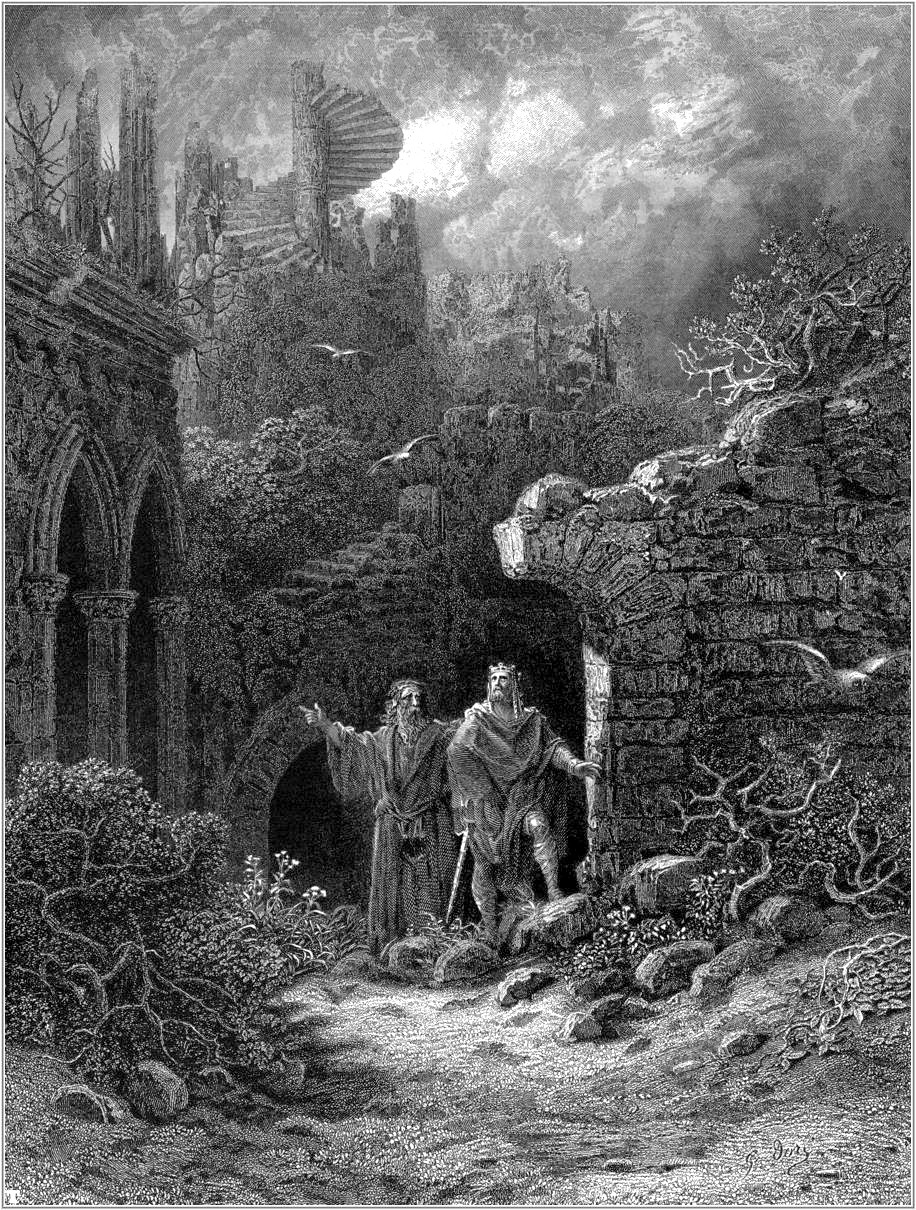

- Public Domain

- Victorian version of King Arthur with the wizard Merlin: Gustave Doré's romantic 1868 engraving for Tennyson's Idylls of the King.

Arthur long sustained his sinking country, and roused the broken courage of its citizens for war.

Deeds of the Kings of the English, William of Malmesbury, c. 1125.

I used to give one-evening community college classes on such eclectic topics as "The Seven Wonders," "Dinosaurs," "Mars," and "King Arthur." Attendance was unpredictable ... except for "Arthur," which always attracted a full house. What I was seeing wasn't a new phenomenon. Since the Middle Ages, the Arthurian legends have consistently captured large audiences with their tales of chivalry and romance. In this and the following two columns, I'll try to explain their timeless popularity.

Around the year 1200, medieval French poet Jean Bodel classified the storytelling themes of his age into three "Matters." The oldest was the "Matter of Rome," which included legendary Greek tales of the Trojan War and the subsequent founding of Rome by Aeneas, together with exploits of real-life military strongmen such as Alexander and Julius Caesar. The youngest, the "Matter of France," concerned the French king Charlemagne and his 12 knightly "peers," including Roland (as in the classic Chanson de Roland). And the third was the "Matter of Britain:" the story of King Arthur.

You might think that a figure as well-known in popular culture as Arthur, together with his court at Camelot, the Round Table of knights and the quest for the Holy Grail, must have at least some basis in fact. Yet historians debate whether a real-life Arthur actually existed -- or if he did, which of maybe six questionable contenders was the prototype. That's because it all happened in post-Roman Britain, during the era often referred to as the "Dark Ages" roughly from 400 to 700 CE, when European historical records are particularly sparse.

Arthur -- assuming he was a real person -- lived in late fifth century Britain, but not until three centuries later is he mentioned by name, and then as a war lord ("dux bellorum"), not as a king. Romanized Britain had enjoyed a roughly three-century era of peace and prosperity in the period before Arthur, from Emperor Claudius' conquest in 144 to the evacuation of the last Roman troops in 410. They left behind a British populace "entirely ignorant of the whole practice of war," quoting the only British historian of that time, the monk Gildas. With the Romans gone, outsiders stepped up the raids. Picts and Scots swept in from northern Britain; Saxons, Angles and Jutes came from present-day Denmark and northern Germany. According to Gildas, the land was devastated with fire "until it burnt nearly the whole surface of the island, and licked the Western Ocean with its red and savage tongue."

What the country needed was a leader capable of rallying the Britons to defend the land from the invaders, maybe someone named Arthur? Next week, we'll look at the evidence for Arthur's role in the singular event that appears to have stemmed the invasions for a century: the battle of Mount Badon.

Barry Evans ([email protected]) is teaching a course at OLLI (826-5880) on King Arthur, dinosaurs and the Seven Wonders in November.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1