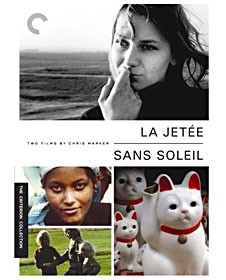

- 'La Jetée/Sans Soleil' Directed by Chris Marker, Criterion Collection

Once again the Criterion Collection has rescued the work of a masterful director from the annals of obscurity. Here they couple two key works by French director/photographer/activist Chris Marker, La Jetée and Sans Soleil , vastly different films that still clearly stem from the same artistic vision.

Marker is a notoriously enigmatic figure. He’s never made public appearances or even allowed himself to be photographed, offering only intentional misinformation about his personal life, leaving us only with is his professional life — work as an early assistant and collaborator with Alain Resnais followed by a series of cinéma-vérité documentaries of his world travels made up his early career, leading to his best-known work, 1962’s La Jetée .

A landmark in the poetic and evocative possibilities of film, La Jetée is set in a post-apocolyptic Paris, telling the story of a man haunted by his pre-war memories who is subjected to a time-travel experiment, subsequently falling in love and experiencing a desire across time. Despite its importance in the lineage of the French New Wave, the film is known by the average video store clerk merely as the source Terry Gilliam pillaged for his 1995 sci-fi flick 12 Monkeys, which lifted the skeletal La Jetée storyline and expanded it to a significantly less risky Hollywood art film. Marker’s approach to the story, however, is notably idiosyncratic: It’s essentially a moving photo essay consisting of a series of motionless black and white photographs, the action and plot conveyed through third-person voiceover. In a scant 27 minutes, stagnant images shift like a poetic slide show to create a world that marries a dream state with a stark, cold reality, fully utilizing film’s (and photography’s) often-neglected ability to stop time (and, in this case, re-work it).

Nineteen years and 13 films separate La Jetée and Sans Soleil , a period where Marker mostly focused on documentaries about political resistance, testaments to his long association with the leftist causes that are often at the forefront of his work. Sans Soleil is truly Marker’s masterwork, a culmination of all his previous explorations as a filmmaker. Made up entirely of travel footage shot by Marker and his colleagues, the film stitches together images from Japan, Africa, Iceland, San Francisco and other places to create a cohesive whole that straddles the line between documentary and fiction. Shot without sync sound, the footage is augmented by voiceover of a woman reading a series of letters from a fictional cameraman relating to the on-screen action (or lack thereof). The narration, combined with a subtle electronic score, lets the inherent inner beauty of the moving images — Marker calls them “the fragility of moments suspended in time” — slowly seep out, building multi-faceted meanings. Children on a road in a volcanic Icelandic town, the hesitant glance of a Guinean woman towards the camera, a homeless Japanese man directing traffic, all are given their own context and significance. At its core, the film is a philosophical essay on the concepts of memory and time, and on the greater implications of filmmaking itself. The masterful cinematography is the sort of thing that can never be intentionally orchestrated on a set and can only exist as an individual’s personal vision in relation to their reality. Through his awareness of this relationship, Marker articulates a bold, overarching viewpoint with a profound understanding of the more abstract nuances of different cultures (achieved largely through contrast), yet he is still able to retain the naïve, inquisitive eye of a traveler. Possibly the only weakness of the film is its density: Only after repeated viewings does the true extent of its depth become palpable.

This release marks the first real stateside appearance of any of Marker’s works on an official DVD. Tragically, the remainder of his five-decade body of work remains nearly impossible to locate even on VHS. Regardless, it’s great that these two films are now widely available, as they remind us that the poetic, visual and philosophical possibilities of film — of art, even — have still yet to be fully explored.

— Spencer Doran, a musician

Comments