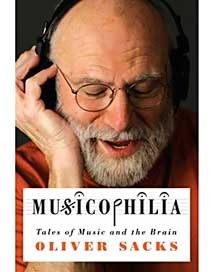

- Musicophilia by Oliver Sacks

Book by Oliver Sacks.

Published by Knopf.

Music, this weird and wonderful do-re-mi, welling up from the same ineffable place as our most basic expressions of instinct and desire — where does this stuff come from? Neurologist Oliver Sacks (Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat) doesn't know, but he offers some strange and compelling portraits of how music can interact with the human brain, to both remarkable and detrimental effects. Over nearly 30 chapters, Sacks touches — sometimes much too briefly — on subjects from amusia (the inability to recognize music as such), to music composed in dreams, to pianists' phantom limbs. There are some amazing stories here, but when Sacks begins to really dig into what feels like the real human interest, the peculiar agonies and ecstasies perpetrated in people by music, he pulls back and digs into neurological minutiae. It's easy to gloss over these parts of Musicophilia, but they happen every few pages; some readers may wish to adopt the strategy of skipping ahead a few paragraphs every time they see the words "basal ganglia."

Of course, Sacks is a neurologist, not an anthropologist, but some cases, like the man who suffers from irreversible memory loss but maintains his ability to play piano and conduct a choir, would be better told by someone who is less interested in brains and more in stories.

It's worth noting that Sacks is largely concerned with classical music. The chapters that deal with musicians' neurological curiosities, like perfect pitch, dystonia (the gradual and inexplicable loss of ability to play an instrument) and synaesthesia (the ability to "see" or "taste" music), focus on classical performers and composers, and one wonders if there might be more interest in a companion volume dealing with pop music. Sacks makes it clear that Musicophilia was written mostly due to his own interest in music (he uses himself as an example of a handful of musical conditions), and in his world music is restricted to its relatively "high art forms" or as a therapeutic tool. Some pop phenomena, like the ubiquity of iPods and the increasingly annoying "earworms" — songs people just can't seem to stop thinking about — are mentioned. Surely these are worth further consideration.

For these few faults, Musicophilia remains compelling due to its subject matter, which reminds us, simply, that music is buried way down deep in our brains and there's nothing we can do about it. It has a hold on humans, one that will likely remain unbroken even as we continually discard music's ephemeral tropes and genres like so many disco LPs. For better or worse, the songs are in our heads — and, one might add, hearts.

Comments