Speculation is stock-in-trade during fire season. Rumors don't spread, exactly, but grow apace with the high grass watered by late spring rains. The state of the season is monitored with the same weather eye of a lookout watching the horizon for lightning strikes. As they did last year, hotshots check their gear, contractors gas up their trucks and battalion chiefs brief their crews on the latest incident protocol. And, like last year, they wait for the calls to come in. Last year, the waiting lasted a long, long time. Whether this year — the hottest on record — will flame or fizzle depends on a delicate mixture of weather, wind, fuel and human cooperation. And, as in every year, fear and anticipation do an uneasy dance. No one actually wants the world to burn, but many look forward to the money that flows when it does.

"I'm excited. I'm breathing heavy already," says Ken Richardson. "It should be a good year but that's what they said last year and I didn't turn a wheel last year."

Richardson is one of thousands of independent contractors who put in bids with CalFire and the U.S. Forest Service every year, hoping to get called out on a fire once the season starts. Contractors range from owners of water tenders and heavy equipment to drivers of personal four-wheel-drive trucks that deliver supplies and personnel to the fireline. Richardson and his wife, Carleen, fall into the latter category. Like many of the contractors, they are retirees who look forward to the seasonal income as a way to supplement their Social Security. In a "good" year, one with plenty of fires, the payoff can be anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000. But whether the initial investment in equipment and training will be returned is a gamble dependent on the vagaries of natural disaster.

"Officials said you can make good money with a bigger truck, so a few years ago I bought a one-and-quarter-ton truck," says Richardson, who has been working fires since 2006. "I sat on it for four years but it's paid off. It'll make money for you. You got to stick with it. You can't quit. Like any investment, you have to take care of it."

The likelihood of being called in to work a fire is a mixture of timing and finances. State and federal agencies are required to go with the lowest bid for contractors, so the less money requested, the greater the chance of being called into work, unless the season is demanding enough to require every hand on deck. All of the bids are made public on the Forest Service's website, so it's not uncommon for contractors to check how much their competition bid the previous year and to undercut them with even lower numbers. On average, a 16-hour day can earn about $260, not including mileage.

It's rare that contractors actually get close to the action; most camps are set up far away from the flames. A good gig is bringing in specialty personnel from out of the area; contractors are paid time and mileage to drive from far-flung national parks to the nearest airport and back. Many gamble on the money-per-mile from long trips like this to compensate for low initial bids.

Richardson, a former paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne Division, says that he "doesn't like sitting down."

"I spent two years, 11 months and six days in the army, and all I did was jungle training. I got out about three weeks early, came home, then, by golly, saw all my buddies go over there to Vietnam and start dying. I wasn't really happy about that. I never saw action, but it was a good thing. The Lord had something else for me to do in about 50 years."

Mike Minton, interagency fire chief for Six Rivers National Forest, says Richardson's attitude is common among seasonal workers.

"There are some financial incentives, but for more people it's a moral calling, a sense of service," says Minton.

As wildfires become more common, so too does the mythos around their suppression. A reverence once applied to soldiers and police officers has shifted onto wildland firefighters, those who "hold the line." Last year a giant billboard went up on southbound U.S. Highway 101, in the middle of Eureka, bearing a portrait of a smudged and sweaty man in yellow, flame-retardant gear, burnt trees visible behind him. In the corner of the board was a tiny silver can, representative of the beer company, urging us to "Thank Our Heroes." The advertisement was reminiscent of the Marlboro Man: pure iconography, rugged valor writ bold to stir our hearts and open our wallets.

As in war, there are a small number of profiteers who chase the action for reasons other than a sense of service. During major incidents, T-shirt vendors often set up outside of command camps, cranking out colorful shirts with the names of particular complex fires. California Fire Tees, for example, "makers of quality incident wearables," still has shirts available commemorating the 2014 Happy Camp Complex fire, which bear a red and white image of an eagle's head screaming from a nest of biker tattoo-style flames. A competitor, Travelin' Ts, out of Reno, Nevada, boasts designs that look like something between an action movie poster and a rodeo belt buckle: The Yosemite Rim Fire T-shirt is a mish-mash of despondent looking grizzly bears and cartoonish firefighters framed by a howling wolf and soaring eagle. A flower of bright flame licks a rim of equally bright green trees. There must be demand among firefighters and camp support to immortalize their experience with these shirts, although Minton and others get a wry expression on their faces when asked about flame-chasers.

"T-shirt vendors shouldn't be on base," says Minton. "They can set up outside, and they do."

(Neither T-shirt vendor returned calls as of press time.)

Inside the base, a makeshift city of tents and trailers houses an alphabet soup of agencies. Generators hum under a hazy sky, fueling charging stations and floodlights. A constant flow of sanctioned vendors — wholesale food trucks, portable toilet and shower providers — rumble across the dusty ground. "Smoke jumpers," "hot-shots" and handcrews — those on the front line of the fire — sleep in shifts on bunks or in tents. Contractors and vendors often bring their own trailers or tents, sleeping a scant six hours before reporting to their supervisors for assignment. Tribal representatives are often present to provide logistical support, advocate to protect sites that have cultural significance or command their own crews. If the incident is close to a major thoroughfare, the California Highway Patrol might be in attendance. Occasionally, fire specialists from out of state will visit to consult with commanders.

All decisions flow through a management hierarchy originally developed by the Department of Homeland Security — the Incident Command System. The ICS is structured like a pyramid, with the incident commander at the top, and a hierarchy of titles (operations, logistics, administration) expanding as needed to a wide base. Every response agency in California puts its personnel through ICS training so they can meld easily into complex incidents without jurisdictional elbow-throwing. Depending on where the fire takes place, the incident commander may be an officer with the National Forest Service, CalFire or another agency entirely.

Seth Stone, a former seasonal firefighter with CalFire, describes life on a fire incident as a mixture of non-stop work interspersed with boredom and fatigue.

"Before I used to do fire, I had all sorts of impressions about how a fire progresses and what sort of danger you might be in," says Stone, explaining that a rigorous training regime helped him and his colleagues focus through the nervous adrenaline of their first few incidents. "When I was in the first few fires, I knew all the steps to take, knew all the operating procedures: hose lay, cut line. You have no idea what will happen, how the fire progresses. After a while, though, you get an intuitive feel for how the fire's behaving."

Wildland firefighting is physically, emotionally and psychologically demanding. One minimum requirement in training is to complete a 3-mile hike (no jogging, no running) with a 45-pound pack in under 45 minutes. Crews may work for 12 to 24 hours a day cutting line (scraping open the turf or cutting down trees to remove fuel for the fire) and laying hose (unravelling hoses toward the fire line). Stone recalls being on duty for 40 days at one stretch during the 2008 fire season. He used his occasional breaks to call his girlfriend and family, a difficult task with the constant sounds of helicopters and trucks in the background. Base camp was usually "dusty and uncomfortable." Sometimes he would turn down the offer to return to base camp altogether and instead sleep, exhausted, on the ground at the fire line.

"If you're a young person and you're working seasonally, it's totally adequate for your lifestyle, but, once you start a family, you need to start thinking about getting a permanent job," he says.

The average monthly pay for a seasonal firefighter with CalFire is around $2,200, with an extra $850 of guaranteed overtime when out on a fire. During the winter, Stone built sets for the Ferndale Repertory Theatre and did other small jobs. (His girlfriend eventually asked him to find more regular employment.)

Stone acknowledged there was a sense of black humor among firefighters, whose livelihood depended on the next lightning strike or campfire gone out of control. A common joke? As they dispersed from an incident, someone would say goodbye to their buddies by shouting: "Show you care, throw a flare."

Mike Minton acknowledges stories such as Stone's with a quick smile. Lore of arson-for-profit among seasonal firefighters has its own cultural cache, but he says actual cases are relatively uncommon.

"There have been enough natural fires in the last several years to provide more than enough work," he says.

And exactly how much work will there be this year?

"What I'm about to talk about is not surprising," said Jeff Tonkin, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service. "If we talked last year, I probably said virtually the same thing. This year is just a little bit better than last year, as of right now."

Tonkin was addressing a roundtable of agency representatives ranging from the U.S. Forest Service, California State Parks, the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office, Municipal Water District and community members, who all gathered at the Six Rivers National Forest headquarters in late May for a meeting on the state of the season. Although post-fire meetings after large incidents have been a common occurrence over the past decade, pre-season interagency planning meetings have only been taking place for the past three years.

Before introducing Tonkin to deliver the forecast, Forest Supervisor Merv George referred to the meeting as an example of the "offensive" strategies agencies could take.

"Traditionally, we've been really good at the defensive side of things, putting out fires. Maybe a little too good. We have more [flammable vegetation] because of that. A major fire incident can use a million dollars a day in resources. I can't tell you how many wonderful things our offense could do with a million dollars a day."

George added that deciding what to prioritize for saving in a major incident can be challenging: Should it be timberland? Structures? Homes? Sacred sites? During any major incident, the monetary and emotional worth of these resources are weighed against wind, weather and historical conditions in a computer algorithm operated by the Wildland Fire Decision Support System. Above all, he stressed, the safety of firefighters and the community should be paramount.

"I love the woods but our guys ... they need to come home to their loved ones."

Tonkin's address to the group was less passionate but equally effective in content. The findings of the National Weather Service supported the wisdom of those waiting on the ground: This could be a very, very bad year. Although late rains have put our region slightly ahead in moisture of where we were last year, it's unusual for them to persist into the summer. Things are going to dry out soon, and they're going to dry out fast. The grass spurred by spring rains will soon become prime ignition sources for lightning strikes.

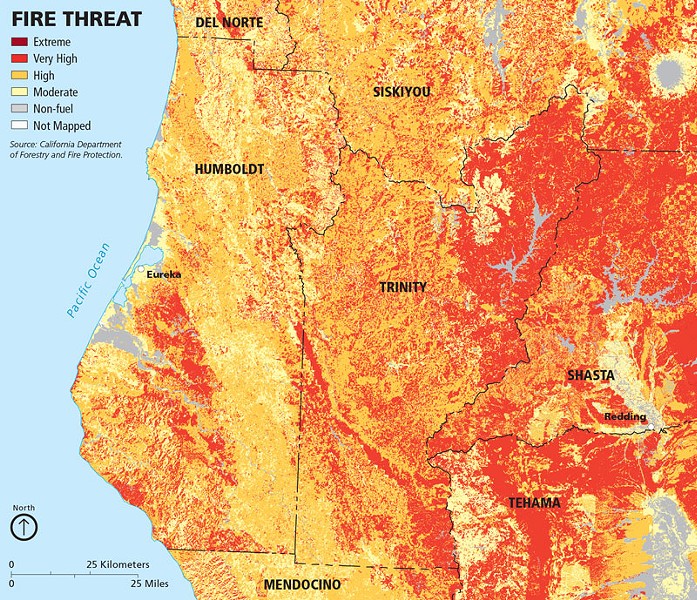

The numbers are stark: This is the fourth year of the most severe drought the state has seen on record. Snowpacks on the Sierra Nevada and other mountain ranges are at only 1 to 2 percent of normal. We are at 40 percent of our reservoir capacity. There have been 1,380 fires in California already this year, including a May fire in Benbow that caused CalFire to send out an ominous tweet: "Don't expect normal burn conditions this year." None of those present chose to use the term climate change, instead referring obliquely to "what the climate is doing lately," or "these things going on with the climate." Tonkin said it was unlikely that the drought will ease in the coming months, that, in fact, there is a "high likelihood that we're going to see above-average temperatures this year."

At this point, Mike Minton broke in to say that the 1,000-hour fuel moisture load was "the worst he had seen [in his] nine years of working fire." The fuel moisture index is used to measure how resistant vegetation is to ignition. This year, large fuels, vegetation that takes 1,000 hours to absorb water from atmospheric conditions, are especially primed to ignite and spread wildfires. Minton added that these numbers are worse on the North Coast than they are inland, which he called "unusual."

The one factor that neither Minton nor Tonkin can predict is lightning strikes. There are some atmospheric conditions that contribute to lightning, but when and where it will strike can't be foreseen with any accuracy until storms roll in. Lightning strikes do tend to peak in July, but even without this leading contributor to wildfires, there is still human error and human malice to anticipate.

The community members at the table stirred uneasily at Tonkin's predictions. Are the lookout towers being funded? Do we have enough water to fight fires this year?

Yes and yes, said Minton. Aerial support should still be able to draw water from streams and rivers.

"We are going to be conservative," said Minton. "But we're not going to see anywhere near the dramatic effects of the drought in the Northwest as in the rest of California."

Later, the room split into two groups for a training exercise. Standing in front of maps labeled "Board Camp Wildfire Scenario," people from the different agencies collaborated to answer such questions as "What are the values at risk for this wildfire?" and "What can you or your organization offer to assist us in the suppression of this wildfire?"

Minton stepped out of the room for a photograph and a private interview. He expressed optimism about improved communication between agencies and how technology, technique and the industry have all evolved in response to a changing landscape and increased frequency of incidents. Still, he said, federal agencies don't have all the resources they need for an especially bad fire season.

"We're redefining normal now," he said.

The California Department of Corrections bridges a crucial gap in resources by supplying inmates to work the fireline. The inmates are subject to the same physical requirements and training as other firefighters, but their interaction with civilians is carefully chaperoned. Seth Stone says inmate crews were among the most fun to work with, although he struggled at first to understand why he wasn't allowed to share candy bars or fruit juice with them.

"They're good workers," Stone says. "They're very motivated and capable and because of the fact that they come out of a lock up, a prison, they're really excited to get out of those prison walls. During training it's explained that if you dole out treats, etc., it disrupts their system. 'Don't give the inmates juice because they'll go back and make Pruno [bootleg liquor] out of it.'"

Prisoners make up roughly half of those fighting wildfires, saving the state an estimated $1 billion a year, according to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. In return, they are offered reduced sentences and the opportunity to escape the monotony of incarceration. Their financial compensation tops out at $3 per day. Some have compared this system to slavery, while others have asked why low-level offenders who can be trusted with handtools and chainsaws are imprisoned in the first place. Sentencing reform in California state prisons has been an ongoing source of concern for those who rely on the inmate crews to fill in their budgetary gaps. Although some agencies have negotiated individual contracts with the jails that now house the majority of California's low-level offenders, still others have lowered their requirements to continue drawing from prisons, meaning that more dangerous inmates may be on the fireline.

Humboldt County is home to two minimum-security inmate fire camps: Eel River, in Redway, and High Rock, in Weott. Eel River Camp Commander Lt. Fred Money said that realignment has not impacted the type of offender or amount of inmates under his supervision. His inmates have "been training all year" and look forward to the fire season.

"They take pride in it. They're going out and contributing something. It gives them a sense of commitment to a goal," Money said in a phone interview.

Normally, state agencies associated with disaster relief such as CalFire will see their budgets wax and wane according to the demands of the previous year. For example, if the agency doesn't use the full allocated budget for field rations in one fiscal year, it will have the leftover amount trimmed the next. But the unprecedented temperatures and drought conditions led Gov. Jerry Brown to declare a state of emergency in 2014, meaning that the agency received augmentation money and the funds to retain additional staff. The Humboldt-Del Norte CalFire unit began hiring seasonal firefighters a full six weeks ahead of schedule in 2015. Unit Chief Hugh Scanlon confirmed the agency retained 100 permanent staff members and, as of late May, hired an additional 70 seasonal personnel. Unlike previous years, the station never completely downstaffed. The seasonal firefighters have been notified that they will return for the season, with an academy to begin in early June. Whether they will earn what Stone calls "that sweet OT" remains unknown.

"It's difficult to have a solid prediction," says Scanlon. "Certainly the fuel predictions are dry and that does not bode well. The forecast from the National Weather Service and forecast prediction center look grim, but you never know until the rainfall is upon you and you have sources of ignition."

Just down the road from the CalFire station in Fortuna, the California Conservation Corps is also gearing up for a hot summer. Normally, corpsmembers in the workforce development program will spend their days doing watershed restoration, removing invasive species or building trails, but fire season means that entire crews of the young people may be called out to do camp support.

"Think of creating a small, operational city," says Raquel Ortega, conservation supervisor at the Fortuna center. "We have 90 members trained and ready to roll. They can get dispatched to anywhere in California and they show up ready to work with the supply crew, do all of the logistical support necessary to feed people, keep people hydrated and check equipment."

The corpsmembers, young people between the ages of 18 and 25, normally earn minimum wage with the Corps, the recruitment motto of which is "hard work, low, pay, miserable conditions and more!" Fire emergency, however, means overtime pay, and when an emergency is declared the center becomes a hub of frenetic activity, with corpsmembers grabbing their pre-packed fire gear and rushing to line up for their assignments. Camp support is often mundane: Corpsmembers may clean up litter, painstakingly check lengths of hose or inventory and load supplies into trucks. It's common for them and other camp workers to return a few pounds heavier, as fire camp meals are calibrated to fuel the physical demands of firefighters, who require about 6,000 calories a day.

A smaller, carefully selected crew of corpsmembers will also make it to the fireline to cut line and lay hose. In partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, the CCC in Fortuna recently certified 30 wildland firefighters. Many will go on to work directly with the Forest Service. This opportunity was one of the major reasons Justin Lusk, 24, left Sacramento two years ago to join the Corps.

"As soon as I got here I started asking a bunch of questions. I proved myself. I showed that I wanted it," says Lusk. Last year his crew went out on four "rolls," including the Coleman and King fires. Lusk is the lead sawyer for his crew, meaning that in addition to the 45 pounds of standard gear in his kit, he carries a chainsaw to cut line. Last year, his first year on the fireline, his chief concern had nothing to do with the fire itself.

"The thing that caught me off guard was the amount that I could do for myself," he says. "I was mostly worried about my own limitations."

This year, Lusk is confident and ready.

"It could be an active season. I'm looking forward to it. I like helping people out and helping our national forests. I hope to be picked up by the Forest Service in 2016."

The chances of Lusk seeing action somewhere in California are good. Last year there were a total of 5,620 wildfires throughout the state, burning a combined 631,434 acres and generating at least $184 million in damage, according to the National Forest Service.

Despite their enthusiasm for a "good" year, most of those who profit off the season seem to have a healthy respect for the emotional toll of natural disaster. In 2011, Ken Richardson was called out to provide support at a location he knew well. One of his neighbors in Ruth Lake had lost control of a brush fire and it spread to consume 1,500 acres, damaging structures and timberland that included Richardson's own vacation home. Richardson went out on assignment, staging his camp just a few miles away from his home.

"You just never know," he says. "You live long enough you can go to fires on your own property."

Comments