Mary's story is like so many: She entered 2020 with high hopes for the new year only to see them shattered three months in. A single mother of two teens, she'd just been offered a full-time job but, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, bringing lockdowns and social distancing, her employer rescinded the offer.

Like many others, she was now jobless and subsequently received aid from the state's unemployment insurance program and California's branch of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (CalFresh). Formerly known as food stamps, the nutrition program gives low-income residents funding to buy food if they meet certain eligibility requirements.

Mary asked to remain anonymous due to the stigma surrounding public assistance programs.

At the start of the pandemic, federal and state governments increased assistance programs to help people navigate the economic impacts of lockdown and social distancing, which brought widespread job losses. They approved stimulus checks, greater child tax breaks, increases in unemployment compensation and benefit hikes to the SNAP program to help families make ends meet. But now that the country is seemingly entering a new phase of the pandemic — with mask mandates lifted, fewer COVID-19 travel restrictions and, according to Cal Poly Humboldt's economic index, the economy returning to pre-pandemic unemployment rates — these expanded assistance programs will soon be lost, leaving people facing a benefit cliff and a return to pre-pandemic struggles.

Of all the relief programs, Mary says the expanded CalFresh SNAP benefits have been the most helpful for her family.

In March of 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees SNAP, allowed states to increase benefit amounts up to the maximum funding amount allowed for all recipients. This has become known as the "COVID-19 emergency allotments."

Through the emergency allotment, Mary and her family are receiving about $300 more per month in CalFresh SNAP benefits, giving her more stability. She says she's been able to purchase more staple items, like rice and beans, in bulk, which then gives her the opportunity to buy more organic fruits and vegetables to create better meals.

"It's the difference between making spaghetti with tomato sauce or spaghetti with tomato sauce and a lot of veggies in it," Mary says. "Kids need that, they need that extra flavor, texture — something that's more than just a survival, make-ends-meet meal."

It's the same situation for many others on CalFresh SNAP benefits.

Steven Pera works at the Jefferson Community Center in Eureka and spoke to a few CalFresh recipients (all of whom also asked to remain anonymous, like Mary) about the expanded benefits. He says all were grateful for the increase, with most saying they were able to buy more food without having to worry about stretching their benefits to last the entire month.

Pera says one neighbor told him she was finally able to buy more organic foods at the North Coast Co-Op, something she couldn't do with the amount of CalFresh benefits she was receiving before the emergency allotments. But when those allotments end, he says she will have to revert to buying cheaper food, eating poorly and relying on local food pantries for her meals.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, based on 2020 data, the average U.S. household spends about $4,942 on groceries a year, or about $412 per month.

The emergency allotments are tied to a federal declaration of emergency made by U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Xavier Becerra. He renewed the declaration back in January with an expiration date set for later this month, but with everything seemingly going back to normal, many believe the emergency declaration is unlikely to be renewed, which would end the expanded benefits and Mary's more substantial meals. If that comes to pass, Mary and her family would again receive the pre-pandemic CalFresh benefits of about $358 a month, or less than $13 a day, to feed a family of three.

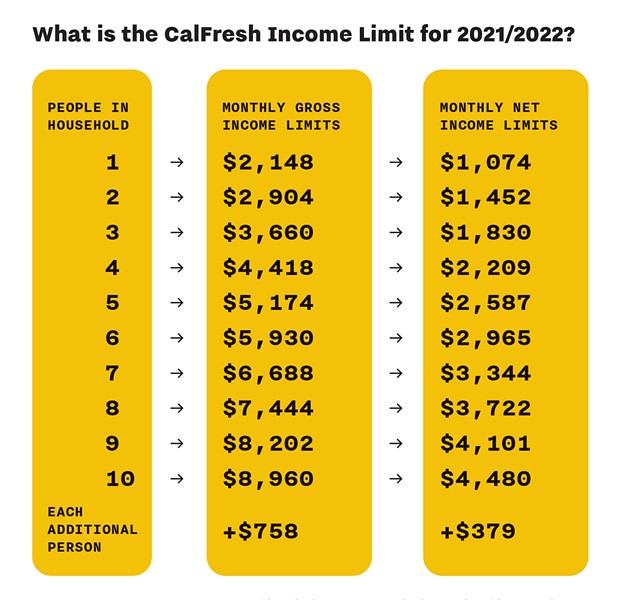

CalFresh SNAP eligibility and benefit amounts are determined by household size and income. To be eligible for SNAP benefits, a household's gross monthly income must not exceed the designated amount set by the California Department of Social Services, which uses the federal poverty level as a benchmark.

A household's gross monthly income must be at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. A single-person household, for example, can't make more than $2,148 per month, while a household with two people can't make more than $2,784 per month and a household of three can't make more than $3,660 per month, or $43,920 a year.

If a person makes $1 over the eligibility requirements for CalFresh SNAP benefits, they no longer qualify, meaning people receiving CalFresh benefits who are performing well enough at their job to earn a raise, or who get a new job with higher pay, might be pushed over the edge of eligibility.

"The rigidity of the eligibility guidelines is heartbreaking," says Heidi McHugh, Food for People's community educator and outreach coordinator, who has been with the nonprofit for 10 years.

For example, consider a family of four receiving $300 per month in CalFresh SNAP benefits when one of the adults gets a raise that brings in an additional $100 per month, before taxes. That added income pushes the family past the eligibility line, meaning the family no longer qualifies for that $300 per month in CalFresh benefits, meaning the adult's raise actually cost the family $200 a month in money to pay for food and other necessities. (This may also impact their eligibility for other programs, such as MediCAL and childcare subsidies.) This "benefits cliff," McHugh explains, places people in the position of opting to decline raises or promotions because they cannot afford them.

"Their income is too high to qualify, yet they don't make enough money to pay for basic needs," McHugh says. "People have to make choices between food, healthcare, phone/internet and utilities. All of this goes back to something that advocates wish for change, it was the fact that the program was called the 'Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.' The idea being that it was supplemental — only it's not a supplement when it's the only money some households have for food, and that's a lot of households."

McHugh has a saying: "There is a mile between eligibility for safety net assistance and self-sufficiency."

If a household meets the requirements, the amount of benefits is determined next.

Appolonia Coan, a staff services analyst with the Humboldt County Department of Social Services, says only a county eligibility specialist can determine how much a person (or family) can receive in CalFresh SNAP benefits.

They start first with gathering household numbers — how many people are living under the same roof. Then, they take the gross household income of everyone in the household who has a job and begin deducting common expenses like rent, childcare and utilities.

These deductions, Coan says, aren't dollar for dollar. Instead, they are based on a percentage of the household's income — how much a formula says they should be spending on living expenses like shelter and utilities.

"So, someone with a $2,000-per-month-rent expense will not always get the same deduction on their budget as someone else with the same rent if they have different incomes," Coan explains.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture also sets maximum deductions on expenses allowed for each CalFresh case without a household member who is disabled or elderly (60 years and older), which is currently $569. This maximum deduction isn't based on region and is the same for 48 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., including California.

However, housing expenses vary from state to state and county to county. According to the Humboldt Economic Index, the average Humboldt County rent in January was $1,943, compared to $904 in Siskiyou County, while other parts of the state — like Los Angeles and the Bay Area — have significantly higher rents that range anywhere from $2,600 to $2,800.

After the eligibility specialist has gathered the household size, the gross income and made the deductions, they're left with the net income, which is then used to determine the level of CalFresh benefits a household will receive within mandated minimum and maximum levels.

For example, a household of one person can't be awarded more than $250 per month, a household of two people can't receive more than $459 per month and, as in Mary's case, a household of three people can't receive more than $658 in CalFresh SNAP benefits per month. The minimum benefit amount for a single-adult household, meanwhile, is just $20.

Eligibility specialists use that chart (and an online system) to calculate what level of benefits a household will receive, which varies from household to household because everyone's income, household size and deductions are different. But because benefit amounts are generated by a formula coupled with each household's unique characteristics, it's difficult for people to guess their eligibility. (Coan says the best way for people to determine their eligibility is simply to apply.)

The looming end of the COVID-19 emergency allotments is poised to have the largest impact on those who had been receiving the minimum allowable allotments because they were granted the maximum allowable benefit for all households instead of what was calculated. So that single-adult household that had only been receiving $20 in benefits is now receiving $250, while those who were already receiving the maximum amount were given an additional $90.

Mary says she's fearful the rollback of the COVID-19 emergency allotments will put her back in "survival mode," adding another level of anxiety.

"These emergency allotments are tied to the federal declaration of public health emergency and as soon as it's lifted, those will not be happening any longer and there are a lot of people who are very, very nervous about this situation and scared, too," says McHugh.

McHugh is also on the Humboldt County CalFresh Task Force, through which she keeps various community organizations and food banks informed about CalFresh and SNAP policy changes like the COVID-19 expanded emergency allotments. She also advocates for policy changes to the SNAP system to help more families in need.

The end of these emergency benefit increases will be dire for seniors and people with disabilities who are living on fixed incomes, like Social Security or other forms of supplemental assistance income, McHugh says.

"[Social Security and supplemental] income isn't going to increase and they've been getting this (emergency) allotment that has finally enabled them to access the types of food that they need to eat to be safe and healthy," she says. "It's kind of sad. Everybody wants the pandemic to go away but, for this group of people, that means they're going to go back to eating very poorly with very little food money."

Although the emergency declaration is slated to end in mid-April, the COVID-19 emergency allotment will last until June because of the way the system is set up, says Coan.

According to Christine Messinger, Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson, as of December 2021, there were 23,054 Humboldt County residents receiving CalFresh benefits. This represents about 13,550 households, or one of every four Humboldt County households.

Messinger says about 29 percent of the people receiving benefits in Humboldt County are under age 18, 55 percent are 19 to 59 years old, and 16 percent are 60 years and older.

Coan says the average per-person benefit in Humboldt County without the emergency allotment included is $166. With the COVID-19 emergency allotments, she says the average benefit per person jumped to $264.

"So, on average, it's giving these households like $98 extra or something, which, it is a really big impact," Coan says. "There's a lot of people who are getting a significant amount of their benefits from the emergency allotment."

In 2021, Humboldt County households received $62.6 million in CalFresh benefits — money that was then spent in local stores — with $22.3 million coming from the emergency allotments. The added $22.3 million in spending locally also likely had a reverberating impact, freeing some recipients' income that otherwise would have been spent on food for other necessities.

In a perfect world, McHugh says, these types of supplemental benefits and programs wouldn't exist, but California is one of the most expensive states in the country, and growing more so. McHugh says the CalFresh SNAP system calculates SNAP benefits using old measurements that don't keep up with the true cost of living.

A report published by the Insight Center, a national economic justice organization working to build inclusion and equity for people of color, women, immigrants and low-income families, calculated the cost of living in California and found that childcare is the highest household expense in 53 of the state's 58 counties, with the other five in the Bay Area having the state's highest housing costs. It also found that having even one child nearly doubles the likelihood that a married couple will teeter on the edge of financial precarity and the hourly wage needed for a single parent with two kids to meet their basic household expenses ranges from $27 in small counties in the northeastern part of the state to around $74 in the Bay Area.

The Insight Center used the self-sufficiency standard created by the Center for Women's Welfare at the University of Washington to determine the cost of being a Californian. It's a "bare-bones" minimum calculation that determines how much a family would need to make in order to meet their basic needs without the assistance of public programs like CalFresh.

The standard is an alternative to the official poverty measure and considers family composition and ages of children, as well as regional housing, child care, healthcare and transportation costs, in addition to miscellaneous costs, taxes and tax credits. (The official poverty measurement, meanwhile, only takes into account food costs.) The self-sufficiency standard has been calculated for 41 states and Washington, D.C., including specific geographic areas like Humboldt County.

In Humboldt, a single-adult household would need to make at least $25,977 to be considered self-sufficient without government assistance programs. A household similar to Mary's of one adult and two teenagers would need to earn an hourly wage of $19.98 — or $3,517 per month and $42,199 annually — to make ends meet without any public assistance.

The Insight Center found that 41 percent of Humboldt County households are living below the Self-Sufficiency Standard, more than double the 19 percent that fall below the official poverty measure.

"It's not food insecurity but money insecurity," McHugh says. "I spend so much time being a cheerleader for this (CalFresh) program and I am. It's the best, most effective way to address hunger but it shouldn't be happening."

For now, McHugh just hopes the federal government will increase benefit amounts to meet higher costs of living.

The most recent increase in SNAP benefits came in last year, when the Biden administration raised benefits by 30 percent. McHugh applauds the increase but says it's only a small step. The emergency allotments, on the other hand, have been huge in helping families afford higher quality, healthier food.

McHugh suggests CalFresh beneficiaries call their local representatives to tell them how much the COVID-19 emergency allotments have helped their households, with the hope they will introduce legislation that would change the benefit allowances to meet the state's higher cost of living.

"The more people that are aware of this, the better chance we have of making some changes," she says. "Be loud."

Iridian Casarez (she/her) is a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or iridian@northcoastjournal.com. Follow her on Twitter @IridianCasarez.

Comments