Two small gravestones with simple, hand-etched inscriptions rest side-by-side at Myrtle Grove Memorial Cemetery, quietly imparting the loss bore by Henry and Clara Reilinger.

One is for their daughter, Amelia, who was 1 month and 20 days old when she died on June 23, 1872. She shares a marker with her brother, whose engraving merely reads "infant son." The second is for another boy, Lewis, who died three years later at 7 months and 15 days.

The couple, both German immigrants, had already lost three other infants before their arrival in Eureka. Four more are believed to be buried with Amelia, Lewis and their brother, but there are no stones.

Perhaps their markers were made of wood, a common practice in the early days, and crumbled over time. Or maybe the parents were too grief-stricken to memorialize their children's passing. It's difficult to say. The Myrtle Grove grounds hold many secrets.

What is known is the Reilingers were not alone. Commissioned in 1861, the cemetery was founded at a time when far too many children did not live to take their first steps.

Nearby, another headstone is dedicated to the three Bryne babies. Little is known about them. The same is true for a little girl buried in another corner of the cemetery who seems lost, her last name different from those on the grave markers surrounding her.

Others defied the odds. Like Hugh Donal McTavish, one of the 167 Civil War veterans buried at Myrtle Grove. He enlisted in the Union Army at 15 and later served in World War I. Born in 1846, he lived to see the United States enter World War II before dying four years short of his 100th birthday.

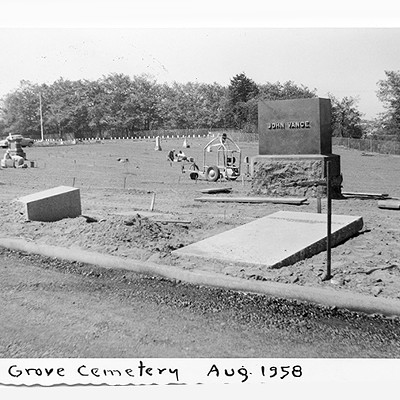

There are also monuments to the city's early kingmakers: Vance, Carson, Buhne. The list goes on. Five mausoleums with imposing granite walls and marbled interiors dot the grounds. Young, old, rich, poor — this was where generations of Eureka residents buried their dead.

But over the ensuing decades, many of the tributes, like the cream-colored oblong stones the Reilingers placed as a last goodbye to their children, began to disappear into the dirt or fall into disrepair — lost to time, the elements and neglect.

That is, until now. Leading the effort to restore this 10-acre corner of Eureka's history is Kirby Nunn, a retired air traffic controller with piercing blue eyes, a no-nonsense manner and a passion for genealogy.

Part groundskeeper, part historian, part alchemist and part bookkeeper, she's mustered together a small cadre of volunteers to bring the grassy expanse back from the brink of obscurity.

"Whatever we do here, if it's continued, it's going to outlive us," Nunn says. "It's a rare opportunity. This is going to go beyond us, as long as people are willing to stand up and perpetuate that."

Like many others, the 64-year-old spent years driving by the stone wall topped with a wrought iron railing that lines Myrtle Avenue thinking the cemetery was closed.

A volunteer for the website Find a Grave, she first walked onto the grounds in 2015, carrying a list of 25 names whose burial sites she hoped to locate and photograph. She didn't find any of them that day. In fact, she still hasn't.

But Nunn found something else: A cemetery in need. Overgrown with grass, decades of dirt covering cracked headstones, she knew something had to be done. So, Nunn made an offer the financially-strapped city parks department couldn't refuse.

"I said, 'I'd like to start taking care of this place," she recalls.

After a partnership was struck, Nunn walked out of city hall with a stack of paperwork and a set of keys to the cemetery gates.

"I went through all the records and almost cried," she says.

What she had acquired was a disjointed archive with gaps and missing pages, an incomplete chronicling of those buried in the cemetery over 153 years. Nunn set about righting that as well. It's a work in progress, updated with newly uncovered headstones.

Still, within those pages, there are hundreds of "unknowns." There are names listed in the cemetery's ledger without corresponding locations of burial. There are plots with no name attached. The search continues to fill in those blanks.

There are, Nunn says, "quite a few question marks."

Behind every grave at Myrtle Grove there is a life story that Nunn and the other volunteers are determined to make sure is told.

"Eureka wouldn't be here if it wasn't for the people who are buried here," Nunn says.

Generations ago, this was a place tended by family members and the fraternal organizations that were so much at the center of the city's early social fabric.

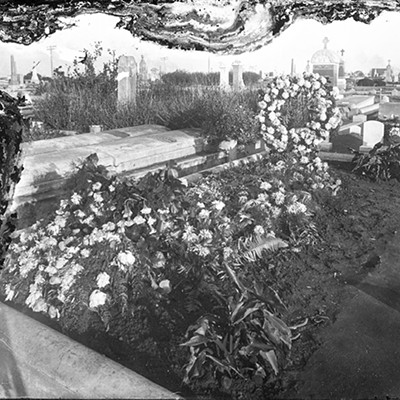

Memorial Day ceremonies were large community events. The organizations and families that owned the plots planted rose gardens and palm trees inside the fences and built curbing to create partitions. A serpentine path in a section known as "the circle," where most family plots are located, once led up to individual gravesites.

When the cemetery was built in 1861, early accounts declared the site covered with a Myrtle tree grove to be "an ideal location far enough out of the main town so there would be no homes built nearby."

"They hadn't heard of urban sprawl," Nunn notes.

As the years passed, the city rose up around the cemetery, families moved away, relatives of the buried died themselves and connections to the place began to unravel. Myrtle Grove became overgrown and fell out of favor, especially once privately-owned Sunset Memorial Park opened in 1932, offering perpetual care.

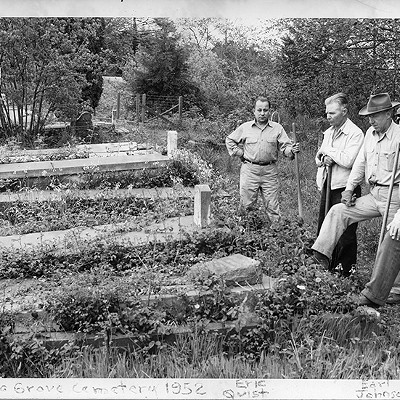

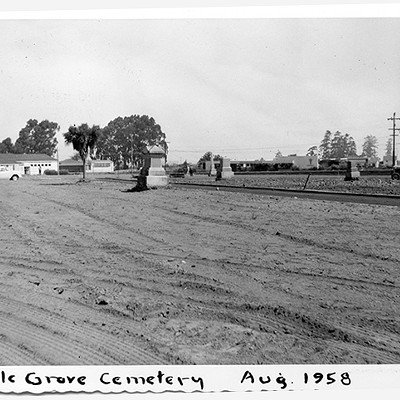

While there were sporadic restoration efforts, the cemetery continued to languish. In 1957, a last great push was made. All the personal touches were removed, headstones were stacked along a fence so the grass could be burned and the ground leveled. A new lawn was planted.

When put back in place, once-standing markers were laid flat to make maintenance easier in an era before weed-whackers. The cemetery's care was then turned over to the city.

At first, the city assigned a supervisor just for the cemetery, but the upkeep of parks eventually fell lower and lower on the city's list of priorities. In recent years, budget crunches have left the park's department with a small staff and few resources to dedicate to a place that seemed virtually forgotten by most.

Without the dedication of Nunn and the other volunteers, Eureka Parks and Recreation Director Miles Slattery says the cemetery restoration project would not have been possible.

"It's a huge thing, not only that they help with the maintenance of the property but they also have the knowledge and the wherewithal to take it back to where it needs to be," Slattery says.

Now, he says, the parks department is exploring the possibility of interpretive opportunities that could tie into plans for nearby Cooper Gulch, noting the general draw of cemeteries with deep histories, like Myrtle Grove.

It's not that Nunn had experience managing a cemetery. Weed-whacking wasn't even in her repertoire before she took on the endeavor. But with a do-it-yourself attitude, she set to work.

Nunn called Arlington National Cemetery to find out how to clean markers and the restoration department at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, itself a National Historic Monument, for tips on repairing headstones.

She learned the right mixture of hydraulic lime to create mortar. When she didn't know how to do something, Nunn turned to the Internet. While she didn't go out recruiting, word of what she was doing began to spread.

"People," Nunn says, "just started showing up."

One of them was Milton Phegley, who says he likes to refer to the tight-knit group of a dozen or so regular volunteers as "Kirby's army."

Phegley didn't have far to go, having just moved back into his childhood home located nearby after retirement. Soft-spoken as he might be, there's no mistaking the note of pride in his voice when he says his family has lived in Humboldt County for four generations.

"The cemetery has always been part of my neighborhood, so it's very exciting to come back to help," Phegley says.

Each volunteer brings something to the table. Several, like Phegley, have a knack for research, providing the narrative behind the lives of those buried here. Another, Larry Jean, is a sculptor.

His work is evident in what Nunn describes as their "flagship stone," which marks the grave of Thomas K. Carr, born in 1860 and one of the city's early settlers. Only portions were visible when Nunn and another volunteer, Tim Kilburn, began digging around and unearthed a jumble of pieces. Jean, who also recreates missing letters, then painstakingly reconstructed what time had broken apart.

Had it been left in that state for another 20 to 30 years, "you wouldn't have been able to see anything," Nunn says. "To me, that's a big deal right here."

Other volunteers, like Kilburn on a recent day, haul dirt provided by the city to fill in hollows that develop over gravesites or provide the brute strength needed to right the stones laid down all those decades ago. Weighing hundreds to thousands of pounds, many have sunk below the surface. More still wait to be uncovered.

"In the beginning, it was finding the stones that were buried," Kilburn says. "That was exciting. Then it moved into raising them back up. That was also exciting."

Once vertical, several have revealed long-hidden secrets.

In one couple's case, the wife's name had been etched on the side obscured by the ground. Another had intricate etchings of a veil that almost appears to move across the polished marble. The top, which had been concealed under inches of soil, is a book carved out of solid stone.

"I think that's the one that really got me excited because it has a book on it," Nunn says. Behind the words there is a semblance of frustration and a drive to make things right.

"When people put special things on headstones, it has significance to the people who put it there. ... That was a significant thing in their life," she continues. "So I became more passionate about standing up all the ones that need to be stood up."

About 50 have reclaimed their place. Another 300, including the Reilinger markers, are still awaiting their turn. Section by section, row by row, the cemetery is rising again.

Walking around the grounds, Phegley is an encyclopedia of knowledge. He seems to know something about almost every headstone, which family married which, where they once lived, which businesses they owned, even what their descendants are doing today.

"Part of the restoration is just getting people aware of and then keeping them interested in the cemetery," Phegley says.

There are people, he notes, with relatives buried here who can help fill in the gaps, but that information could disappear if they're not asked.

Kneeling on the ground, Phegley gently wipes dirt away from the headstone of the little girl whose name differs from those in the adjoining plots.

Plucking at dandelions with bright yellow flowers that have encroached on the grave, he wonders if maybe family friends offered to bury her in their plot. Hers is yet another story waiting to be told.

Looking out at the lawn she just finished trimming, Nunn says they've accomplished much in just a couple of years. She gestures across the grounds at the interspersing of headstones. "We raised that one over there, those over there," she says.

The work has been made easier by the efforts of community members like Brian Papstein, who helped secure grants from the Sign and Ruth Smith Fund of the Rotary Club of Eureka and the Christine and Jalmer Berg Foundation.

Those funds, which Slattery says are kept in a donation account earmarked for the cemetery, paid for a bright orange rider mower from Shafer's Ace Hardware — which just happens to nearly match the shade of Nunn's trademark T-shirt. The business also put together an extended package of supplies and tools for the volunteers to use.

Like the saying goes, Nunn says, it takes a village.

An Air Force veteran, Nunn's initial goal had been simple: Prepare the grounds for a Memorial Day event, something the cemetery hadn't seen in years. She started in the veterans' section and raised a flag there last November for the first time in decades.

But, there's still more work to be done.

The list is endless: keeping the grass mowed, fixing headstones, raising them up, updating records and uncovering the stories behind the estimated 6,000 men, women and children buried there.

When the ground is soft enough, the volunteers search for more markers, meticulously walking row by row, pushing a probe that resembles a child's pogo stick down into the ground, inch by inch.

So far, more than 200 have been reclaimed.

"Every day, every time we've gone probing," Nunn says, "we've found something. One day we found seven but that was an unusual day."

With 6,000 recorded burials and 2,200 markers, there are still more out there — including the 25 that Nunn originally came looking for.

"There are some we're never going to find. Some were made of wood and disintegrated. Or, they never had a marker," Nunn says.

That's especially true for one section, the rolling lawn of the north-east corner, which stands in stark contrast to the rest of the cemetery. Here, except for a scant three headstones, the expanse is bare — devoid of monuments or polished marble markers with fond farewells to departed loved ones.

This is where the county buried its poor or those with no family to claim their remains. As they were in life, many of the 200 or so people laid to rest here remain relegated to the margins of society. Some of their death records offer no more about them than a racial epithet followed only by a first name.

"One thing on my wish list is to put up a monument in the county section with the names we do know," Nunn says.

More research to be done. More stories left to tell.

While the 10-acre parcel might never be Arlington National Cemetery or Green-Wood, her goal is to bring Myrtle Grove up to the level of an historic park.

"How do you go on a historic tour of the Vance building and go by the Ingomar Club and not come here and look at where Vance and Carson were buried?" Nunn asks. "It just all goes together."

Looking through the lens of decades spent in city planning, Phegley says he also sees more than just a cemetery.

"It's valuable open space where people can come and walk and learn about the county's history and see the handiwork of the people of the past," Phegley says.

Someday, when everyone has been found and their markers put back in place, the cemetery will just be in need of maintenance. For the time being, Nunn says, she's happy to help.

But, hopefully at some point, others will stand up to help pay their work forward.

Nunn looks down at a block of old stone. The letters on the obviously home-made marker were almost unreadable. "It was done out of love," she says of the rough etching. "It was someone who cared about that person and did what they could."

Once they find out who the grave is for, Nunn hopes to have another marker made, not as a replacement but as something to let people know who is there. Having spent decades researching her own lineage, Nunn has journeyed to cemeteries all over the country to visit family markers.

She wants to make sure that those with relatives at Myrtle Grove have the same opportunity, ensuring those buried there are never forgotten.

"People have legacies in their children and grandchildren. I don't have children," she says. "This is it."

Myrtle Grove Memorial Cemetery: How to Help

Interested in volunteering at the cemetery? Contact Kirby Nunn at [email protected].

To find out more about those buried at Myrtle Grove, go to the Find a Grave website and click on Find a Cemetery, enter in Myrtle Grove and select the state of California.

For questions or to share stories about relatives buried at Myrtle Grove Memorial Cemetery, visit www.facebook.com/myrtlegrovememorialcemetery.

To donate to the cemetery's fund, contact Eureka Parks and Recreation Director Miles Slattery at 441-4241.

Kimberly Wear is a staff writer and assistant editor at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 323, or kim@northcoastjournal. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1