Troy Nicoloni was still at the Woodley Island office of the National Weather Service before dawn on March 11, 2011, after what had been a long night for the then warning coordination meteorologist who was monitoring updates after a massive rupture of the subduction zone off the coast of Japan.

Later upgraded to a magnitude-9.1 earthquake — one of the largest recorded in modern history — the first alert had been issued just before 10 p.m. PST. Soon, news began trickling out about the ensuing tsunami that reached parts of Japan's shoreline within minutes, overwhelming protective barriers, killing thousands and sweeping away entire cities.

Now surges from 5,000 miles away were barreling across the Pacific Ocean at the speed of a jet airliner and a wide swath of the West Coast, including Humboldt County, was under the highest assigned threat level — a tsunami warning — meaning low-lying areas areas like King Salmon and Manila were potentially at risk of destructive flooding.

In those early morning hours, Nicolini coordinated with representatives from area tribes, local emergency officials and their counterparts in Mendocino and Del Norte counties, who collectively decided to sound the local alarm at 4:30 a.m. At the appointed time, Nicolini sat down at the NWS command console and pushed a sequence of buttons that sent out a signal to remotely trigger the region's warning system.

Simultaneously, across hundreds of miles of the North Coast, sirens blared, NOAA weather radios switched on and programming on television and radio was automatically interrupted to announce a tsunami was on the way. Law enforcement went door to door in vulnerable areas to urge residents to evacuate and a shelter was established at Redwood Acres. The Samoa Bridge was closed and school districts across Humboldt County canceled classes for the day.

"With everything happening at the same time, there was perfect clarity, I feel like, in northwestern California about what was going on," Nicolini said in a recent interview with the Journal.

Three hours later, the first waves began to arrive. Humboldt was spared but the Crescent City Harbor was not. While most of the Del Norte County-based fishing fleet was able to leave before the surges hit, dozens of boats were crushed and many of the docks destroyed, leaving $20 million in damage. One man was killed after being swept away while trying to photograph the tsunami near the mouth of the Klamath River.

"It was a powerful experience," Nicolini said. "When we issued the tsunami warning, I went outside of my office and I could hear a few sirens in Humboldt Bay and I was like, 'Wow.' It was really pretty profound and they worked really well at the time."

But a lot has changed since that morning 11 years ago, when the sirens wailed their last warning.

In a test last March, nearly half of the county's 12 sirens — those located at Orick, Clam Beach, Arcata, Trinidad Rancheria and Big Lagoon — were silent, casualties of standing sentinel along the local coastline for years, battered by the salt air and the North Coast's notoriously damp conditions. Another in Manila had been inoperable for even longer.

Now Ryan Derby, the county's emergency services manager, is tasked with weighing options for moving forward in a vastly changed emergency notification landscape that, unlike in 2011, allows local officials to reach thousands of people via text, email and reverse-911 calls to landlines within minutes.

"I see last year, even though a large number of sirens failed, as a good way to measure the effectiveness of the system," Derby said. "For us, it's a success because it allows us to hyper-analyze how we reach people and where, and how we focus our efforts."

While the siren's circle of horns measuring some 3-feet high and 4-feet wide cut an impressive figure set atop poles across the coastline from Fields Landing to Orick, the reality is their use is limited and the devices are only one of many notification methods deployed in the case of impending tsunami.

Their main purpose is to serve as a warning for those out on the beach or in the water if waves from distant shores pose a significant danger, when officials generally have hours to get out the word before impact. In the case of a locally generated event, there likely would not be time to set them off.

Complicating matters is the lack of a designated funding source for maintaining or replacing the sirens, meaning the county would need to apply for a federal grant to cover the cost, which would require a 25-percent match. With initial estimates for buying new sirens coming in at $500,000, not including installation and required studies, the question being raised is: Are they worth the cost?

"The general consensus is that sirens are really an antiquated alerting technique that is kind of like comparing the use of a pager to the use of an iPhone 12," said Derby, who's spent the last year gathering input from state emergency officials, the National Weather Service and the Redwood Coast Tsunami Work Group, among others. "There are a whole slew of new options we have that would be more effective for that distance-source event."

Over the last 100 years, five tsunamis have caused damage on the North Coast, according to Cal Poly Humboldt Geology professor emeritus Lori Dengler, an expert on earthquake and tsunami hazards and hazard reduction. Each of those tsunamis came from points around the Pacific — Chile, Alaska, Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and Japan.

"These are the type of tsunami that the official alert system is designed to notify us about," Dengler said. "The 2011 Japan tsunami is a good example. It took over nine hours for the tsunami to reach our coast."

The region's greatest tsunami threat remains in our own backyard — the Cascadia subduction zone, a nearly 700-mile fault line running from Vancouver Island to Cape Mendocino capable of unleashing a magnitude-9.0 or greater megathrust earthquake, which could be followed by devastating surges that sweep well past the coastline within minutes.

Dengler said earthquakes are the most common source of large tsunamis, with one in the magnitude-7.5 or higher range posing a "significant risk."

"People will feel the shaking from an earthquake of that size for more than a 100 miles ... and the shaking will last a minute or longer," she said.

In that case, as Derby, Dengler and Nicolini all emphasized, Mother Nature is the alarm, with intense, prolonged shaking, the sound of a loud roar or the ocean suddenly receding to expose the sea floor — all signs it's time to immediately head for higher ground, regardless of whether a siren sounds or an emergency alert pings your cell phone.

"When that fault ruptures, the damage to coastal infrastructure will likely be significant, disrupting power and communications systems," Dengler said. "I would be very surprised if any of the systems that are part of the official warning system will be operational, considering the shaking and surface fault rupture we are likely to experience."

The North Coast experienced a taste of what the Casacadia subduction zone can do back on April 25, 1992, when a small corner ruptured near Petrolia, producing a magnitude-7.2 earthquake that shook the ground with such force it overwhelmed the ability of seismic-equipment in the area to even register the intensity at points and — for the first time ever recorded along the West Coast — sent a locally generated tsunami to shore.

In the aftermath, landslides shut down roads, water mains burst, windows shattered, a wide swath of the North Coast was left without power and fires destroyed the Petrolia post office and a business center near Scotia.

Near the epicenter, a 15-mile-long section of coastline was thrust several feet in the air, leaving tide pool creatures trapped above the ocean's reach, with the same movement causing a corresponding drop in the Eel River Valley floor, forever altering the local landscape.

Two powerful aftershocks — a 6.5 and 6.6 — followed the next morning amid a series of smaller ones. For those who were here, it almost seemed like the earth would never stop shaking.

Dengler said she's neither "thumbs up or thumbs down" on the future of the North Coast's sirens, but notes the general consensus that those currently in place are obsolete and "not worth trying to revive."

"They are basically a 1950s-60s design and the systems were not designed for our damp, salty coastal environment," she said. "That means the expense of purchasing new sirens, installing them and the continued expense of maintaining them. County officials need to look long and hard at the benefit-cost ratio."

But, Dengler said, there's also a need to recognize the reassuring presence the sirens evoke, even if it provides something of a false sense of security.

"If some or all of our sirens are removed, it is important to help everyone understand that this doesn't mean they are now more exposed — that there are plenty of systems that are more likely to work that will notify them of an impending tsunami," she said. "But the last thing we want is a population dependent on sirens, who thinks sirens are more important than feeling the earthquake shaking."

There's always more education that needs to be done on that front, Dengler said, with tourists, visitors and those who are homeless hardest to reach and educate about the dangers posed by the clashing tectonic plates off the Humboldt coast.

"Some of these groups can be reached through stronger ties with hospitality industries," Dengler said, noting tsunami-prone Hawaii has a long history of educating tourists and disseminating alerts. "I have been to several hotels that provide earthquake/tsunami flyers in all hotel rooms. This needs to become the norm — along with information about fire escape routes."

She said she'd also like to see organizations that work with the unhoused help spread the word.

"But my biggest concern for all of these groups is the local Cascadia earthquake and tsunami threat, and not the tsunami coming from Alaska or Japan," Dengler said. "Whether we have working sirens or not really doesn't make any difference if the tsunami source is right under our feet."

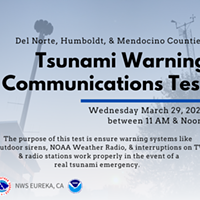

That's why preparedness events like the annual ShakeOut Earthquake Drill in October and the tsunami warning tests each March play such a vital role, she said, allowing local emergency officials to do a full test-run of the alert systems, while also educating residents about how to prepare, warning signs to watch out for and what to do in the case of a major seismic event, including practice walks on evacuation routes in tsunami hazard zones.

Dengler said she hopes the North Coast can someday be as prepared as the residents of Langi Village on Simeulue Island. Although 100 years had passed since a devastating tsunami last hit, the residents there continued to follow advice handed down from generation to generation: When there is prolonged shaking, head to higher ground.

So on Dec. 26, 2004, when the ground shook with intense force, the entire village did what they always do: They grabbed the children and placed those who couldn't make the walk into carts and marched up a hill to safety. Within minutes, 30-to 45-foot high waves from the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami began to arrive.

Even without access to warning systems, or even electricity, everyone in the village survived, as did all but seven of the 75,000 people who lived on the island.

Dengler said when she asked one of the villagers if they had ever questioned the need to make their way to higher ground with every large quake, "they just looked at me as if I were crazy and said that every earthquake just might be the one to produce a great tsunami and that every large one was an opportunity to practice how to evacuate."

Humboldt County is not alone in considering its next steps with warning sirens.

Just over the Oregon border, Curry County commissioners voted in 2019 to discontinue siren use, finding the cost outweighs the benefit in an age of cell phone alerts and other notification systems. Farther to the north, Tillamook County made the same decision nearly a decade ago.

But nearby Del Norte County, which bore the brunt of the 2011 event and where memories of the 1964 tsunami that killed 11 people and destroyed 29 blocks of Crescent City still resonate, officials opted a few years ago to stay the siren course.

Derby said two main options are currently on the table in Humboldt. The first, he said, is to leave the sirens in their current state with no maintenance and allow the devices to "be a really good conversation starter" about the threat of tsunamis on the North Coast and the other warning systems now in place.

Top among those is Humboldt Alert, the county's emergency notification system, which allows residents to receive information on everything from floods and fires to tsunamis. For tourists and visitors, most cell phones now come equipped with the federal Wireless Emergency Alert system in place, which sends geographically targeted, text-like messages to anyone in the area of a public safety threat, as long as their location signal has not been turned off.

But that doesn't mean those left behind by the digital divide — or who, for whatever reason, can't be reached where they are by those alerts — will be left unprotected, Derby said.

Since last year, all Humboldt County Sheriff's Office patrol vehicles have been equipped with high-lo sirens to quickly warn threatened areas in the event of evacuations, whether from wildfire, flooding, tsunami or other life-threatening emergencies.

And with hours to work with in the case of a distance-source tsunami, warnings can be broadcast over vast stretches of coastline via the civil air patrol while law enforcement is sent out to shut down coastal access. Then there are the more traditional alert methods: TV and radio emergency broadcasts, NOAA radio alerts and reverse 911 calls.

"With the advanced technology and the ability to use high-low sirens and dispatch people out to the hazard areas before the event hits, I'm confident that we'd be able to notify people of a distance-source event without the use of sirens," Derby said.

The alternative would be to initiate an impact study to pinpoint the highest priority areas for siren replacement and apply for a federal hazard mitigation grant, which would cover 75 percent of the cost. That scenario, Derby said, would mean "looking at just a handful" of strategic sites.

At the end of the day, sirens are just noise machines, alerting people that something is happening but not what it is or what to do. And, the network is only sounded if Humboldt County is under a tsunami warning, when surges with swirling currents could potentially breach beyond beaches and the harbor, putting homes and businesses at risk. They don't sound in the case of a lower level advisory, like the one that occurred in January after an undersea volcano erupted near Tonga, when the main danger was strong currents and unpredictable wave heights along the coast.

The advantage of mobile alerts and physical evacuations, including the use of civil air patrol, is that officials are able to get out real-time information with clear directions, whether that means giving instructions to evacuate or shelter in place, or even to sound the all-clear, Derby said.

"At this point, just looking at the potential cost of replacement of the sirens vs. the benefit ... the benefits are somewhat negligible," he said. "It's hard to justify putting the cost forward for that project when we have other mechanisms that may be more effective."

The office of North Coast Congressmember Jared Huffman, who strongly advocated for preserving the nation's tsunami warning system when President Donald Trump proposed shuttering one of two warning centers and cutting funds for the deep-sea monitoring system that provides real-time information on a tsunami's movements, said it has not received any requests for financial assistance from emergency officials in Humboldt but "stand ready to help if needed." State Assemblymember Jim Wood's office said staff would look into the issue, while state Sen. Mike McGuire's office did not immediately respond to an inquiry on the subject.

Derby said his recommendation to bolster existing more modern methods is not to say that sirens haven't played a role in keeping coastal communities safe, but now their usefulness is more as "a large, visual symbol of preparedness and protection" that breaks the ice and starts people talking.

Nicolini agreed, describing them as akin to a really good coffee table book.

"The great value sirens have still to this day is that they get the conversation going like nothing else we do about tsunami safety," he said, adding that inevitably the first question at any preparedness event is always about sirens. "They are icons of preparedness. There is just something about them."

Nicolini said he's proud of the work done to install the current network of sirens — free hand-me-downs from Diablo Nuclear Power Plant in San Luis Obispo that arrived in January of 2006. Ironically, he noted, late Supervisor Jimmy Smith was able to broker the deal with PG&E because the nuclear plant was upgrading its siren technology.

About six dozen were distributed across the North Coast, with the NWS, local tribes and officials in the tri-county area working together to design a remote activation mechanism that utilized the same signal being used to trigger alert systems already in place.

"We felt it was a beautiful solution because it integrated everything," Nicolini said. "If we issued a tsunami warning, it would interrupt television and radio stations, it would turn on people's personal NOAA radios that are activated by the same signal and it would turn the sirens on."

So, on the morning of March, 11, 2011, all local officials had to do was agree on a set time. As smoothly as the system worked that day, Nicolini said, there are now better tools that weren't available back then.

Nicolini said he's not against the siren system but keeping metal devices with moving parts that house sensitive equipment operational in a marine environment is a constant challenge, with most of the current ones now "corroded to oblivion."

And they make more sense in some communities than others, he said, pointing to Shelter Cove, which separately maintains three sirens and where cell phone coverage is limited, and Del Norte County, where the population is more centralized and the community has a long history of destructive tsunami events.

In fact, Nicolini said, he's been one of the longest holdouts. "They just have an iconic symbolism of preparedness that I just always thought made them worth the effort."

But with everyone from school children to grandparents now carrying cell phones, there are simply other systems that can get out information "more reliably than an outdoor siren could ever do," he said, especially in combination with all the other emergency alert tools available in the county, including NOAA weather radios, emergency broadcast alerts on TV and radio, hi-lo alert sirens on police and fire trucks, and the ability to send out the civil air patrol.

Ultimately, Nicolini said, the key to any emergency notification system is redundancy. But when the big event that's most likely to be life-threatening comes, there won't be a text or a siren. There will just be shaking.

"It's going to be Mother Nature telling you, 'You have 10 minutes to get out of there," Nicolini said. "So that's the most important warning system, by far."

Kimberly Wear (she/her) is the Journal's digital editor. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2