When Charles Martin addressed the Judge, his condition invoked the sympathy of everyone in the room. "Standing in the prisoners' dock, he presented a pitiable sight," the Humboldt Times described in an edition printed later that day. "Though young in years, he was nevertheless a broken, decrepit being, trembling in every nerve and muscle."

Martin had been arrested for using drugs and the effects of Martin's "debaucheries" were clearly evident as he stood before the court and detailed his downward spiral into addiction. One indulgence, he said, had led to another, until he was powerless to resist his cravings. Abstinence had become a torture he simply could not bear.

Confessions like Martin's play out with a numbing regularity in Humboldt County's courtrooms with one caveat. Martin appeared in the Eureka police court more than a century ago, on Jan. 23, 1881. The root of his addiction, opium.

"This is actually not our first opioid crisis," says Candy Stockton, who currently serves as chief medical officer of the Independent Practice Association, co-chairs Rx Safe Humboldt and was recently named Humboldt County's next health officer. "While some things have changed, too much has stayed the same."

Opiates, derived from the milky sap of the opium poppy, have been used for thousands of years to treat a variety of ailments including coughs, diarrhea (which could be fatal) and more. They also mimic the body's natural endorphins and can relieve pain, induce sleep and enhance users' mood to the point of euphoria.

"Opiates are also highly addictive," Stockton explains. "Those who become dependent eventually need the drug for their brain to feel normal."

Despite these challenges, Opium's benefits (and perhaps addictive qualities) supported its early spread to ancient Greece, Persia and Egypt. By the sixth or seventh century A.D., opium had reached China and East Asia through trade along the Silk Road. In the 1700s, the British empire conquered a major poppy-growing region in India and brought opium, and addiction, back to England. Britain then began to ship opium into China, where the drug's addictive qualities steadily increased demand. The British used the soaring proceeds of their drug sales to purchase and profit from Chinese luxury goods, such as silks and teas. China's attempts to stem the tide of opium (and addiction) into the country ultimately failed. During the First Opium War (1839-1842), the British government used military force to keep Chinese ports open to opium and during the second (1856-1860), the British and French succeeded together in forcing China to keep opium legal in China.

"Many blamed the Chinese for the spread of opium but it was really our fault," says Stockton, referring to white or European Americans, noting the still-familiar pattern of blaming perceived others for local (and national) addiction problems.

By the time of California's gold rush in 1850, opium addiction was well entrenched in Chinese society and Chinese laborers arriving to work on western railroads and goldfields brought their customs — and opium — with them.

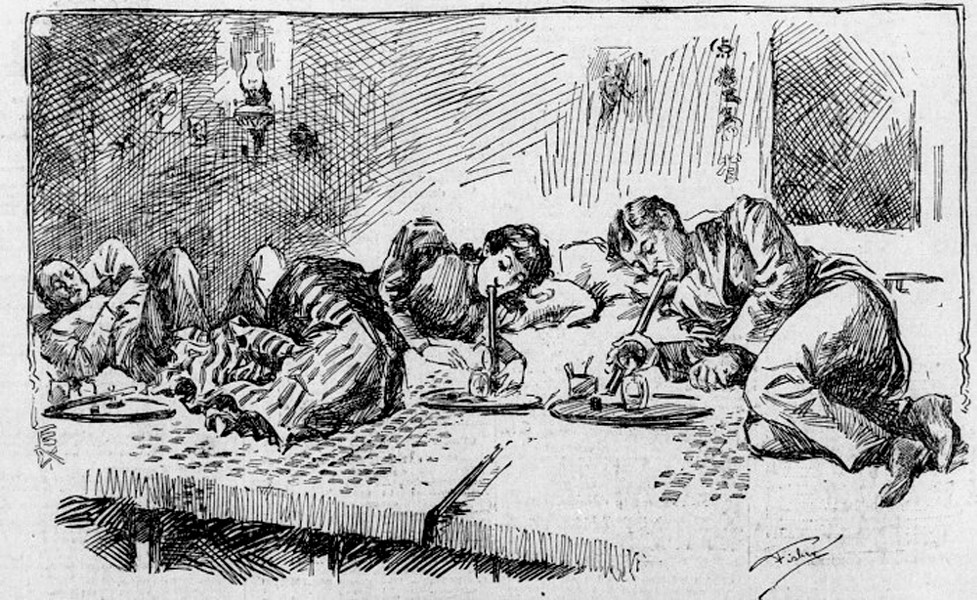

Widespread alcohol abuse and associated violence and mayhem had been familiar problems in the "settled" areas of the North Coast in the second half of the 19th century, but opium also gained a foothold in the region. By 1881, Eureka hosted at least four opium dens catering specifically to white residents, as well as others serving the Chinese community. While a Humboldt Times reporter sympathized with white users seeking a temporary escape or "sensual enjoyment" from the opium pipe, the reporter noted that the "pallid countenance, fleshless frames and shaking limbs" of the community's otherwise promising young men was alarming. The son of a liquor dealer could not be pulled away, nor could a local attorney whose addiction sometimes found him in court "too stupid from the effects of the drug to attend to the matters in which he was retained." Local prostitutes were known to seek a "luxuriant repose beneath the clouds of smoke," but worse in the eyes of provincial white residents, so were at least some "respectable" women.

This spread of addiction into more mainstream populations seemed to be at the root of local concerns. In 1875, San Francisco became the first California city to pass legislation making it illegal to maintain or frequent an opium den, though it did not ban sales, imports or other uses. While the law did not specify race, according to a 2014 analysis offered by Stanford Law School, it was enacted to address "opium-smoking establishments kept by Chinese, for the exclusive use of white men and women and prevent those of "respectable parentage" from using the drug. Dens specifically catering to Chinese smokers were generally left alone. Other California communities took the same approach — focusing erroneously on "protecting" white residents from perceived corrupting influences through prohibition rather than addressing root causes of addiction.

By 1883, the Eureka press was calling on officials to rid the community of opium dens and "kindred evils." Establishments were raided and operators and smokers faced fines and stints in county jail, though disparities were obvious. On March 12, 1884, the Humboldt Times reported that Walter Simmons, charged with being in a house where opium was sold, faced a fine of $10 while Sing Joe, a "Celestial" (Chinese emigrant), was fined $20 for the same offense.

On March 21, 1883, following the arrest of a "Chinaman, Chinawoman and suspected white man" in a Shasta County opium den, the Humboldt Times reported the expulsion of that county's Chinese residents. In 1885, after Chinese gang members were alleged to have accidentally shot a white Eureka city councilmember, local officials, already primed with anti-Chinese sentiment, followed Shasta's lead and forced nearly all the city's Chinese residents onto a ship bound for San Francisco. Arcata citizens, after blaming their Chinese residents for opium dens, gambling and prostitution, soon expelled that city's Chinese community members as well.

Predictably, problems continued.

"Even when you can limit the supply of a drug, the demand doesn't go away," Stockton says. "People just turn to something else." And that is what seems to have happened in 1885. Local stories and community protests against opium dens disappeared from the county's newspapers with the expulsion of Humboldt's Chinese residents but the racist action did nothing to address addiction in Humboldt. While opium use continued to plague other communities, Humboldt County's drug challenges took an unexpected turn.

Without Opium ...

Morphine is made by extracting the alkaloids from an opium poppy plant and its pure form is 10 times stronger than opium. Like opium, morphine was used extensively for pain management beginning in the 19th century and also causes physical and psychological dependence. By the end of the Civil War, it was estimated that at least half-a-million soldiers were battling morphine addiction. Survivors of the war moving west brought morphine, and addiction, with them. After opium dens were closed in Humboldt County, addicts turned to morphine.

"Give me only a few drops; for god's sake, give me just a little," the Humboldt Times quoted a "shrunken-faced ... morphine fiend" as saying to a New York pharmacist in its Oct. 29, 1885, issue. The story was one of many highlighting the horrors of morphine addiction, which was then sweeping the nation.

While some had already linked the growing drug crisis to irresponsible physicians and druggists sharing the opiates too freely, doctors had few choices and patients in pain begged for relief. With few effective alternatives, physicians continued to prescribe opiates and again, Stockton points out, we see parallels.

"Part of the reason for the most recent opioid crisis was the expectation that patients, even those recovering from surgeries or severe physical trauma, should not have significant pain," she says. "Doctors face pressure to alleviate patient suffering — opiates are incredibly effective and readily available."

But it isn't just physical pain people are desperate to escape, observed Andrew Carpenter Wheeler, an American journalist writing under the pen name Nym Crinkle, in an editorial published in the Sept. 6, 1887, Humboldt Times.

"I have found that in most cases the [opiate] habit had been contracted, not as usually stated, in a desire to escape physical pain, but in the endeavor to escape mental troubles," Crinkle wrote. "Morphine, like opium ... is a great remorse killer ... a temporary Lethe." Lethe is a river in Hades with water that when drunk made the souls of the dead forget their life on earth. Men were the most frequent drug users, Crinkle pointed out, but women were not immune (see Laudanum sidebar).

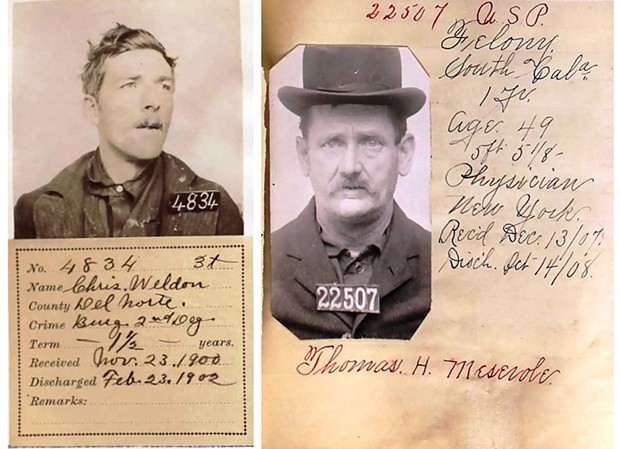

- California State Archives

- The mug shots of Chris Weldon (left) and Dr. Thomas Messerole, two men whose struggles with addiction were chronicled in the Humboldt Times.

Cycles of Trauma

When Ferndale pioneer James Weldon died in the 1870s, it fell to his widow Elizabeth to raise their eight children alone. Uneducated, she pulled the family from its once successful farm to work in a Eureka laundry. The older children did what they could to help to pay the bills, but their earnings were never enough. Not long after his father's death, Elizabeth's second born, David, was sent to San Quentin for robbery. David's younger brother Chris soon followed after stealing a gold watch and attempting to pawn it in Eureka. For the younger Weldon, the first conviction launched a years-long pattern of incarceration and release and, though he wasn't identified in the local paper as a "morphine fiend" until 1892, his addiction and criminal behavior were surely related. On Nov. 24, 1900, 15 years after his first conviction, the Del Norte County Triplicate announced Chris Weldon had been arrested and sentenced to 18 months in Folsom State Prison for burglary. Weldon, the paper noted, was addicted to narcotics and committed the thefts to get drugs.

"It is so painful because the conversations we have today are the same ones we had 100 years ago," Stockton says. "People suffer and turn to what is available to treat their suffering."

Chris Weldon had lost a parent, she points out, experienced poverty, had a family member incarcerated and likely experienced both physical and emotional neglect. While Chris Weldon likely just counted himself the victim of a hard life, today we refer to these events as adverse childhood experiences, or ACES, and understand more about the impacts of childhood trauma. Recent studies have consistently shown that individuals with higher ACES scores, meaning they have experienced more adverse childhood experiences, are more likely to have poor health, suffer from addiction and engage in high-risk behaviors in adulthood. As early as Oct. 1, 1896, the Humboldt Times printed the findings of a New York physician working in the Tombs Manhattan detention complex, which noted that "victims to the opium and morphine habits" accounted for approximately 85 percent of inmates there.

According to the First Five Center for Children's Policy, about 31 percent of Humboldt County residents have an ACEs score of four or higher, roughly double the percentage of other California residents. Humboldt County's 21st century rates of addiction, premature death, overdoses and petty crime reflect this distinction.

In the 19th century, Weldon was far from the only local resident stealing to feed their addiction. Throughout the 1890s, confirmed "morphine fiends" like Charles Murray, Dave Dillon and Frank Whiting were often before a judge on petty criminal charges. In 1902, one local judge committed morphine addict Fred Grant to the county jail for three months with the express hope "he might recover from the use of the drug sufficiently to be able to abstain from its use." A reporter described Grant as a "pitiful object," struggling in vain against his addiction.

Treatment options at the time were few and far between and both law enforcement and users were desperate. By then, physicians recognized that sudden withdrawal was a "torturing ordeal" considered by many to be cruel and barbarous, but for many like local physician Thomas Messerole, the white-knuckle approach of sudden abstinence seemed to be the only option.

On July 31, 1905, Messerole stood before Eureka's police court and begged the judge for 30 days in jail, hoping incarceration would help him break his "dreaded" habit of cocaine addiction. Despite "diplomas and credentials galore," the doctor hadn't practiced medicine in years and worked in local lumber camps. The judge sentenced him to 20 days instead and less than six weeks after his release, Messerole was arrested and given a "floater," or forced eviction, from Arcata. Messerole got as far as Eureka before he was again before a judge after burglarizing a house for valuables he planned to sell for cocaine.

"You may send me to San Quentin," the despondent doctor said. "I don't care."

The doctor then shared "a pitiful story of his past life and suffering." Years before, after a hard ride, the doctor took a little morphine to ease his discomfort. He used it again and "gradually the habit gained possession of him until he was a fiend." He successfully overcame his addiction but then suffered an accident that tore and lacerated his arm. Treating doctors injected cocaine to help him cope with the pain and "the cure was all off." He was soon a "fiend" again, but this time using cocaine. Life was now a misery, he said, and he suffered all the time. Declaring Messerole "only a victim of the drug," the district attorney and judge sentenced him to the county jail instead of prison, hoping 30 days would be enough to clear the drug from the good doctor's system.

"Messarole's story also is particularly important because it highlights the disparities in how the justice system responds to those who suffer from addiction," Stockton says. "Just look at the criteria for addiction, or substance-use disorder, that we use today."

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the handbook used by healthcare professionals in the United States and much of the world as the authoritative guide to diagnosing mental disorders. According to the DSM, people have a substance use disorder when they can't control their substance use, their use creates social problems, they use in unsafe or risky settings or become physically dependent. But, as Stockton pointed out, many of these things are only obvious when substance users also face financial, housing or employment challenges. While those who lack the privacy of a home or have less control over their jobs have less margin for error in managing an addiction, professionals can often access substances of choice, use them in the safety of their own home and make social and professional adjustments to avoid detrimental impacts. More often than not, substance use needs to be extreme before those users experience significant consequences.

Messerole had reached that point, but sympathy from the courts in deference to his education and profession protected him until July 13, 1907, when the Los Angeles Herald reported that the former doctor, a confirmed morphine and cocaine addict, was arrested for counterfeiting. He was convicted and sent to San Quentin for a year. It is unclear if the year gave him a chance to break his habit, but Stockton says probably not.

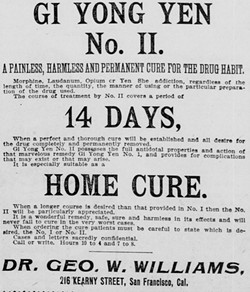

- California State Archives

- A newspaper advertisement promises a "home cure" for addiction.

"The body develops a dependence on the drug," she explains. "During physical withdrawal, individuals experience the opposite effects. If you take opiates to alleviate pain, that pain is magnified. If you were constipated, you get diarrhea. Sedation becomes insomnia. These acute effects last for seven to 14 days — and that's the easy part."

Stockton says opiates also stimulate the feel-good receptors in the brain but, over time, the body recognizes that this is unhealthy and adjusts.

"Dopamine is critical for everyday functioning, let alone pleasure," she says. "After regular use, the brain's system that recognizes dopamine is damaged."

This is especially problematic for individuals from high-trauma environments who are already battling a dopamine deficiency.

"Sometimes when someone uses opiates, it is the first time they've ever felt normal, which is a powerful incentive to use again. When they stop, they feel incredibly low," Stockton says, adding that addicted rats in lab studies can become so apathetic during withdrawal that many lose their will to live and die. "It takes two to three years for the brain to reset pleasure receptors to the previous 'normal,' which may have been low in the first place. Without medical intervention, recovery from addiction is very difficult — even impossible for some."

This hold over the body was recognized by some as early as 1881. "The opium habit is a disease of the central nervous system and is not subject to control by the will," Frederick Heman Hubbard observed in his book The Opium Habit and Alcoholism, published in 1881. "We cannot reconcile them with the idea that it is a mere habit, indulged in with a desire to stimulate, and in satisfaction of a depraved appetite." Instead, Heman said, victims of the drug became powerless in their use to the point "women of culture and natural refinement pawn their jewels or sell the feathers from their beds to secure the requisite amount of opium ... ."

The Willis Family

In the summer of 1901, 28-year-old Owen Willis left his wife, son and baby daughter to fend for themselves and the Humboldt Times followed their story. That July, May Willis, a confirmed "morphine fiend," was often seen wandering Arcata's streets with her little boy at her heels, "his plaintive cry at fear of being separated from his mother" heard by many. The family lived in a tiny "hovel" at the end of J Street, where the children were often left alone and hungry. After witnessing this tragic circumstance and fearing the Willis baby would die without intervention, Constable Webster appealed to the Ladies Aid Society for help. The Ladies then turned to County Physician Falk, who said he had no jurisdiction to intervene.

By August, Owen Willis, also addicted to morphine, was back in Arcata but matters did not improve, and the Ladies pleaded for intervention. County officials countered they had no authority and were forced to "let the matter stand as it was." Fortunately, the baby survived and was taken in that fall by a local couple. The boy, however, was left with his parents.

Over the next few years, the couple traveled throughout Humboldt County. Sometimes, the "small, frail-looking" May Willis posed as an injured woman needing a dollar to secure a ride while her husband stayed out of sight. Other times, the couple begged outright for handouts, their little boy in tow. In 1904, the couple had another child and the county supervisors finally stepped in, ordering the district attorney to secure custody of the Willis children. The parents, they declared, were "hopeless morphine fiends and in their pursuit and use of the seductive drug lose all parental instincts and all respect for themselves."

May and Owen Willis fled with their children in the face of this declaration but were caught in Rohnerville. The children were taken from their parents and parceled out to others in the community. Because there were no effective treatment options or social services offered at the time, the family was likely never reunited.

"Unfortunately, this story is too familiar, even today," Stockton says. "Though we have more social services and treatment programs now than we had 100 years ago, we still need to build more resources for children and families. We need to identify risks and address trauma and poverty. We are also too quick to remove children from their family of origin and culture without recognizing that separating them creates additional trauma."

That trauma can have long-term consequences. In fact, on May 13, 1905, the Humboldt Times reported that a 9-year-old boy at the county hospital had contracted scarlet fever. The boy was the son of the "notorious Willis couple," the paper noted, and had been an "inmate" of the hospital for about a year.

"We need to ensure that families can access basic mental health care and treat illness, as well as mental health issues like depression and anxiety," Stockton says. "We also need to support them better with opportunities for safe and stable housing."

Failing that, Stockton predicts, we will continue to see stories like that of the Willis family again and again over the next 100 years.

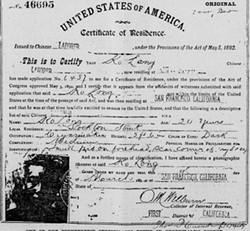

- California State Archives

- A fake immigration certificate, which became commonplace in lucrative smuggling operations.

Prohibition Takes Hold

Stories like those of Weldon, Messerole and the Willis family were likely no surprise to doctors and others following the impacts of addiction at the time, yet opioids provided key ingredients used to manufacture critical drugs needed to address a variety of illnesses. In fact, in December of 1887, the secretary of U.S. Department of Agriculture encouraged American farmers to "turn to the cultivation of opium poppies."

The key, many believed, was restricting access. As early as the 1880s, health experts were demanding more control over the distribution of opium, morphine and addictive drugs, and doctors were encouraged to limit their prescriptions and monitor patients for signs of addiction. Legislation was proposed and enacted to better regulate the access and sale of legal drugs but control on the streets remained fragmented and sporadic. In fact, in November of 1897, the Missouri Supreme Court declared the law against opium smoking and opium dens unconstitutional because it interfered with the right of men to smoke whatever they choose. As the country moved into the 20th century, many opiates could still be purchased without a prescription from neighborhood drug stores.

Many laws were passed in the early 1900s to restrict the transport and sale of opiates and to label them so the purchaser would know "what poison he is taking or giving to his children." In 1907, California became the first state to prohibit marijuana in an addendum to the Poison Act, which made it illegal to sell or use cocaine or opiates, such as opium and morphine, without a prescription.

It would take the passage of the Harrison Tax Act in 1914, however, before the federal government took complete control, regulating the production, importation and distribution of opiates and cocaine. The law also imposed taxes and finally put physicians in charge of access to these potent and addictive drugs. But the law also restricted physician access to the drugs and, by 1917, doctors were prohibited from prescribing opioids to treat addiction.

"Doctors realized that to support those recovering from addiction, they had to help patients adjust their dopamine levels — just to keep them functioning," Stockton says. "Without medical treatment, many patients won't be successful. Their dopamine levels are so low they lose their will to live."

Doctors don't treat addiction with opioids so that patients get high, she clarifies, but instead use them as a medical treatment to keep patients functioning as their bodies and brains work through the withdrawal and healing process.

Because these laws limited legal access, many turned to other sources and Humboldt County's illicit drug use proliferated. On Jan. 26, 1923, the Humboldt Times argued the death penalty should be imposed on those convicted of dealing illegal drugs. "The dope peddler is a murderer, just as surely as is the highwayman or other renegade who uses a gun, but his offense is the worst and most devilish in the whole category of crime," the writer declared. "With a stealth and cunning almost defying detection, the miserable thief of life, health and happiness, the despoiler of youth and honor, slinks, like a pestilence into the home, the school and the workshop and spreads death and ruin."

The death penalty, though extreme, seemed to be the only solution, the editorial argued.

"Of course, there will be those who will gasp in horror at such a proposal," it concluded. "But only because they did not know and appreciate the danger, much less the enormity, of the crime of the dope peddler."

Breaking the Cycle

Throughout the 20th century, officials, medical professionals and families continued to battle the ravages of addiction. And in the mid-1990s, the over-prescribing of OxyContin sparked a new epidemic of addiction and death. Fortunately, Congress passed the Narcotic Treatment Act in 1974, which allowed a practitioner dispense Schedule II narcotic drugs for maintenance and/or detoxification, allowing a more medically informed model of addiction treatment. Combining medication with mental health and other supportive services, Stockton says, seems to be the most effective approach to treatment, though not all challenges are medical. Stigma, she says, remains a significant barrier.

"When an oncologist treats cancer, he or she doesn't question if the patient deserves treatment, even if the patient smoked or engaged in other behaviors that contributed to their health issues," she says, noting that too often addiction is treated as a moral failing instead of an illness that can be treated to help patients achieve better, healthier lives. "We also need to focus on the root cause of addiction because limiting supply simply sends the user searching for another drug to help them. Until significant changes are made, we will just continue to repeat the cycle."

According to the Centers for Disease Control's National Center for Health Statistics, more than 100,000 people died of a drug overdose in the United States during a 12-month period ending in April of 2021, an increase of 28.5 percent from the 78,056 deaths during the same period the year before. Fentanyl, which is lethal in much smaller doses, increases these dangers but, Stockton says, we are not without hope. Building foundational supports for children and families, she says, is key.

"We absolutely need to address racial and economic disparities and provide equitable access to medical care and housing," she says. "We also need to have a more effective response to (the)crisis and provide addiction treatment to all who need it." Supporting programs like Eureka-based Waterfront Recovery Services, the first detox program certified by the California Department of Health Care Services to provide medically assisted treatment for drug and alcohol withdrawal, is a good start. Stockton also believes other advances are coming as medical providers learn more about addiction and its causes.

"Knowledge is power," she says. "With the digital age, our access to information is very different. We understand so much more than we did before, and we can more easily share that information. We really don't need to be talking about another drug crisis 100 years from now. We can learn from our mistakes."

Lynette Mullen (she/her) is a Humboldt County-based writer and historian. Visit www.preservinghistories.com to learn more.

Comments (2)

Showing 1-2 of 2