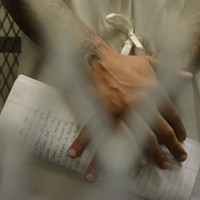

The room is about the size of a large walk-in closet. Its walls are industrial beige, the floor gray concrete. Six cages of diamond metal mesh line a wall, each roughly the width and height of a coffin. The men enter one at a time, each flanked by two correctional officers. Their hands are cuffed behind their backs, attached to shackles around their waists. Their clothing is monochromatic, monastic: white pants and white shirts, the uniform of prisoners inside Pelican Bay State Prison's Secure Housing Unit. The shirts tie vertically with laces up their chests. On the backs are large, block letters: CDC prisoner. They enter the cages one at a time, then turn and thrust their hands through a small slot to have their cuffs removed. Inside they sit or lean against small metal stools, clutching notebooks and pens. This will be one of the few times in the week that they will see other people, have human contact, leave the cells where they spend up to 22 hours a day alone. This is Cecelia Holland's classroom.

Holland enters the prison shortly before her class begins, stumping past the administration desk with a battered rolling suitcase that contains her teaching materials. Her gray hair is rumpled, her black sweater covered with cat hair. She lives in Fortuna and teaches creative writing at the prison on Thursdays and Fridays, spending the night at a local motel. Nature did its best to knock the 74 year old down last year, with a flu and then stomach surgery canceling classes for several weeks in the fall. But on this mid-winter day she rolls with momentum through the hectagon-shaped maze of the institution, thrusting her I.D. through the windows at each checkpoint, nodding at the camera so the man in the guard tower will buzz open the gate that leads to a long, open space between the administrative office and the main prison complex. She is determined to see the men she calls her "boys."

Holland, an author of fantasy and historical fiction novels who has published about a book a year for the past 40, teaches creative writing to men housed in both the general population and SHU units. The men she has come to see today in the SHU are part of the California Department of Correction's decades-long attempt to disrupt gang leadership in the prison system by sequestering known or alleged gang members in solitary confinement at the remote prison. The practice came to national attention in 2013, when four rival gang leaders organized a two-month hunger strike to protest the indefinite nature of solitary confinement. The men waiting for her have elaborate tattoos across their knuckles, faces and necks. Several of them wear the same thick-rimmed, prison-issued reading glasses. Their hair is buzzed close to their skulls, and attached to the outside of each cage is a laminated card with a mugshot and a number. Holland says the SHU is "hell on earth." Her students, however, are "wonderful."

"They're all very different," she says. "There are no ordinary guys in there. And they like me. They trust me. They come in [to class] with their prison faces, then they relax."

Holland taught creative writing at the prison for close to a decade before budget cuts ended the Arts in Corrections program in the early 2000s, during what Holland refers to as the "throw-away-the-key era." Expanded programming for SHU inmates was one was one of five key demands in a 2011 hunger strike. Ultimately, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, in collaboration with the California Arts Council, restarted the program in 2013. The CDCR now invests $8 million in the program annually. Scholarship programs, such as the William James Association Prison Arts Project, help pay for Holland and several other teachers, including a guitar instructor and local artist, to visit the maximum security prison several times a week. The money is good, she says, but that's not why she does it.

"They are so sweet," Holland says of her students. "There are huge reservoirs of kindness and humanity not destroyed by prison that are there to be tapped."

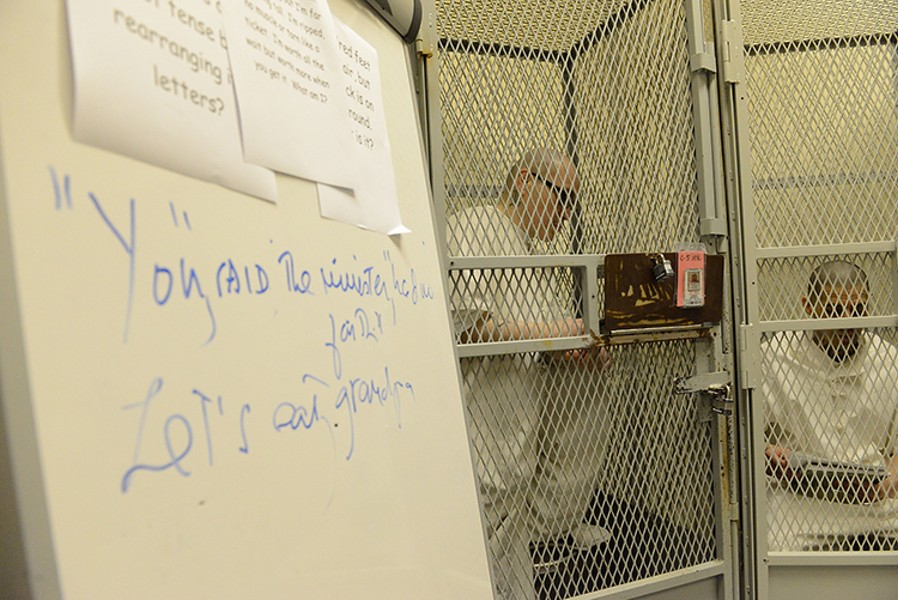

With a correctional officer sitting near the door, Holland faces the row of men in cages. She starts each class with what she calls "chit-chat time." They often talk about football, discuss the previous week's events or the weather. Then the men read work they've written since the last class. One starts by saying he's been reading a book about people who struggle. He opens his notebook and, visibly nervous, begins to read aloud a prose poem.

"Deep down in my soul I know I will never go home," he says. "There is no escape for death that gets closer to me... This world I live in is a brutal, cold world... It feeds on concrete and blood... I am no longer mine... The world I live in is a prison of my own doing."

Holland begins her criticism with a reaction: "Whoa."

"That's good, don't you think?" She looks around the room. The other men nod. Then she gives more precise feedback.

"The central thing, which I think is very good, is it's something you can feel," Holland says. "It starts out with something you can feel, the cold. Nothing is colder than Pelican Bay in the winter."

Several of the men agree. The next one begins to read. Several of the stories are about prison, about the SHU. One has a funny and eloquent story about a prisoner befriending a mouse that makes the men and the correctional officer laugh. He finishes with a shy smile, drinking in Holland's approval. Another reads a dialogue-driven story about a carjacking from the victim's perspective. One reads about scoring a touchdown at a football game.

Holland says there are recurrent themes in her students' work: homesickness, death, murder, missing your kids, falling in love.

"There's a lot of, 'I didn't realize it would turn out like this,'" she says, "And sometimes there are sappy love poems."

She's currently in the process of compiling the prisoners' work into a book, which she will self-publish this month, sending copies to each of the writers and the Pelican Bay library. The review process from the prison was onerous, however, with correctional staff scouring the stories to make sure there were no gang messages.

There are a few restrictions on what the students can write: The CDCR doesn't allow their work to be explicitly sexual and Holland doesn't like it when they write about drugs. Holland's own fiction often contains graphic battle scenes; she is unflappable.

"They love to get shocking in their stories," she says, referring to men new to the class. "It doesn't happen twice. The first time they see I'm not shocked, they stop."

In a retrospective essay written for a zine called Free Reading after the program was halted in 2003, Holland described her bond with the men she taught, saying its strength came, in part, from the fact that she wasn't an employee of the prison. When the program ended, Pelican Bay's arts coordinator took over the class for a while, but it wasn't the same.

"That's why the class works for them," Holland explained in the essay. "Because we are alike, they and I, in one key way — we resent authority, and love to kick it over. Only, I put my violence in books, and theirs was written in blood."

Reflecting on her own words more than a decade later, Holland says maybe she was "a bit melodramatic." Things have changed since the program started up again. In the 1990s, classes didn't go into the SHU. In order to get solitary confinement inmates to class, the prison must dedicate staff to processing them out of their individual cells, escorting them to the classroom individually, monitoring them during class and repeating the process in reverse. Holland also enjoys her general population classes, which are held in a large gymnasium, but the SHU students, she says, are particularly fun, often "outrageous" with their words and their thinking.

"When I meet a new group of guys, I start out by telling them, 'There's really only one question in the world, which is, 'What the fuck?'," she says. "Then it becomes more visibly relaxed. The main thing is I want them to be true to themselves. They really enjoy having a voice. Prison tries to take away everything that's theirs. They can't even wear their own clothes. I tell them their voices are theirs."

She has never worried about her own safety in the classes. The prisoners are protective of her. She's required to wear a bulletproof vest, but she finds it stifling, hot and heavy. Although details of past crimes often end up in their stories, she doesn't ask or investigate why her students are in prison.

"I try not to find out but they generally end up telling me," she says. Some are in for armed robbery, for murder, for gang activity. Some are serving life sentences. Their crimes, she says, don't bother her.

After reading their work, Holland leads an exercise on grammar, writing bad sentences on the whiteboard and having the men figure out where there are dangling participles, incorrect pronouns.

"Haha, I told you you were geniuses!" Holland crows when her students identify an offending preposition.

On the wall behind Holland hang framed photos of recent graduates from another program, Building Resilience, an inmate-led course that helps prisoners explore past behaviors and identify unhealthy relationship patterns. Graduate caps adorn shaved heads, with white uniforms poking out beneath purple robes.

Lt. John Silveira, a spokesperson for the prison, says programming like the creative writing class and Building Resilience make a "huge difference" in the men with whom he works. Silveira was a corrections officer and a counselor before moving to his current position.

"I really see them having a little hope," he says. "I see them being in charge of their own brain again. It changes their demeanor, their interactions. I like it."

He adds that the prison has plans to introduce other programs, such as an entrepreneurship class called Defy Ventures and a course called Getting Out By Going In that uses peer-led groups to change prison culture.

Holland and another teacher, Julie McNiel, both see their work through the lens of culture. Holland, whose novels often take an anthropological approach to historical events, compares it to "Margaret Mead finding Samoa." McNiel, a Eureka-based artist who has been teaching at Pelican Bay for three years, says her students often arrive at her class with fully formed artistic styles.

"People come in with their own language," she says. "They already have their own mode of expression."

McNiel, who teaches at the prison twice a week, has to work with a limited array of materials. The general population students might paint with ink, acrylics or watercolors, but nothing metal, glass or ceramic makes it past the front door. In her SHU classes, the students are allowed only paper and pencils. Everything she brings in is carefully counted by staff at the beginning and end of each class. Still, she says, students produce what she considers extraordinary work with what they have at hand.

"A lot of the work is complex, beautifully drawn," she says. The pen and ink drawings are often highly detailed, with pointillism and shading. Every spring McNiel collects work for an annual art show at the Del Norte County courthouse. Her students usually paint nature scenes: flowers, birds, landscapes. She tries to bring as much nature into the institution as possible, using pinecones and scenic photographs to inspire the students. As with the writing, there is some censorship from the prison staff. Some cultural and religious motifs, such as rosary beads, are also affiliated with gang membership. Work that crosses the line is confiscated.

"I encourage students to stay away from that imagery," says McNiel. "I need to have good relationships with staff on the inside. I don't want to compromise the program; it's bigger than me."

McNiel says the students are hard-working and resourceful. In one class, she stumbled over how to cut paper without scissors. The men used a thread from one of their uniforms. She is fascinated with how people move inside the institution, the physicality of how prisoners walk at a certain pace, how their arms are restrained. An animated series inspired by her time at the prison will open at the Morris Graves Museum of Art on Jan. 6.

For the final part of Holland's one-hour class, the men take turns reading aloud an abridged version of Ernest Hemingway's short story, "The Snows of Kilimanjaro." The men do a lot of reading in their free time but she disapproves of their taste for mystery and crime paperbacks. She tries to pick authors whose works will have some resonance with her students' experiences: "The Shawl," a short story by Cynthia Ozick about a woman hiding her baby from guards in a concentration camp; "On the Brighton Road," a ghost story by Richard Middleton. They also like the poetry of Robert Frost, she says. Like Hemingway, he's technical and accessible. She tried to get them into Faulkner but it didn't take.

"The Snows of Kilimanjaro" is about a man dying from gangrene. He is angry with his wife and angry with himself for the choices he's made. The fever and pain make him hallucinate. Holland shows the men a picture of the mountain, Kilimanjaro.

"Remember, he's screwed everything up and now he's blaming his old lady," she tells them. Many of the men trip over Hemingway's dated words. But they are riveted by the phrase, "Death had come and rested its head on the foot of the cot and he could smell its breath."

"That's so cool, you can just picture it," one of the men says.

"Always make something so you can see it and touch it and feel it," Holland says.

They discuss the story, its style, the feeling of death moving in, the thwarted dreams of Hemingway's protagonist, who died with stories he hadn't written down.

"He's a writer that doesn't write anymore," Holland says. "As a writer, I can tell you that's the very worst."

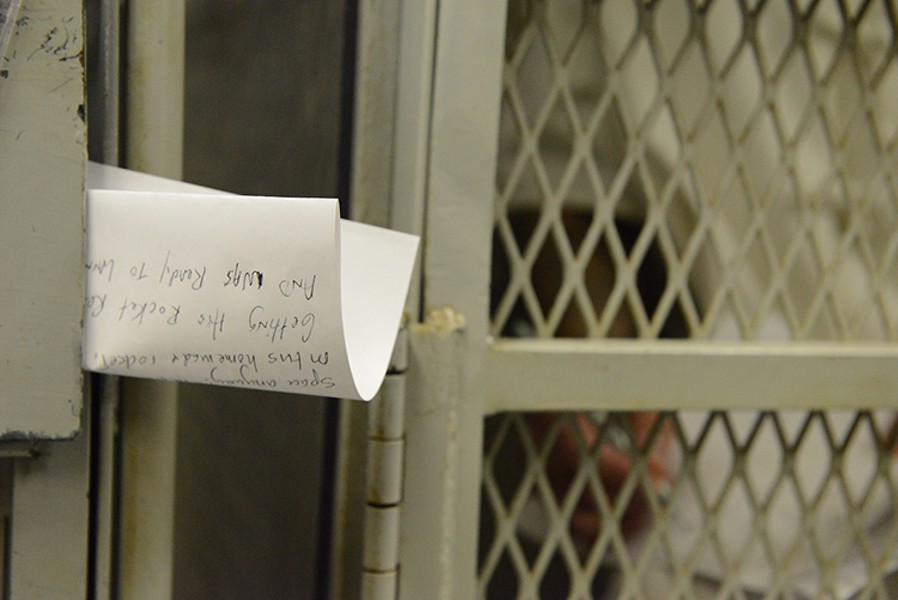

After the reading, the men do a pass around exercise, each writing a sentence on a piece of paper then, with the help of the correctional officer, passing it along to the man in the cage next to them. The stories that result are usually funny. One man writes about winning the Nobel Prize "despite Cecelia Holland nagging me."

"When you win the Nobel, will you mention me?" she asks him. He flashes her a mischievous grin.

As she ends the class, Holland gives out assignments.

"Your spelling sucks," she tells them. "But your writing is good, standard English. Get the words down, and when you get back to the house, correct the spelling. For next week, write some love poems. Not to me."

Holland puts her papers back in the rolling suitcase. The guard stands. She looks tired. The class, she has said privately, can be exhausting, "like performance art." Now the men stand close to the doors of their cages. Soon they will turn and thrust their hands through the small slots to be handcuffed once again, then be led through the concrete corridors back to their solitary cells. But now their teacher comes to them one by one, puts her hands where there is the smallest gap in the cell door and touches her fingertips to theirs as she says goodbye.

"See you next week," she tells them one by one. "Keep writing."

Linda Stansberry is a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @LCStansberry.

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4