John Fullerton was skeptical, and not without reason. He'd been serving on the Eureka City Schools Board of Education for about a decade when the subject of getting another school bond on the ballot began gaining some traction. Fullerton, a local certified public accountant, was a newly elected board member when voters approved a $32.5 million bond measure in 2002. He'd also sat through the aftermath, when segments of the community grew angry, feeling their money had been squandered on cosmetic facelifts and remodeled offices, a pottery building and a television studio, as the district's decades-old school buildings slipped further into disrepair. The bond's flagship project — the renovation of Eureka High School's Jay Willard Gymnasium — never even got started before the district ran out of money, one of a host of promised projects left on the shelf.

Now, a dozen years later, the district was looking at returning to voters, hat in hand, this time hitting them up for a nearly $50 million bond, with district homeowners still facing decades of property tax levies from the last go around. "My exact words were, 'This is too much and this is too soon,'" Fullerton recalled, adding that he saw a need for $9 million in projects throughout the district but didn't think voters would approve more spending, much less the $49.75 million the district was going to ask for.

Fullerton was wrong. In November, 14,623 people in the district cast ballots and the bond — Measure S — passed by 41 votes. So how did the district and its supporters get this thing approved, even as voters were being hit up simultaneously for additional taxes by the county and the city of Eureka? One could argue it's because the Support Eureka City Schools campaign raised nearly $65,000, widely believed to be the most ever raised by a bond campaign in Humboldt County, which it poured into print, radio and television advertising, as well as phone banking. (The Humboldt County Elections Office doesn't keep historical campaign finance data, so it's impossible to verify the claim, but it was passed onto the Journal by numerous people involved in local school finance.)

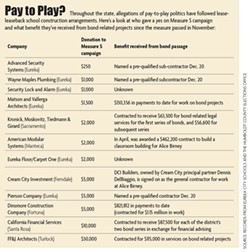

How did the campaign fundraise so successfully, especially with some voters still smarting from the 2002 bond? By targeting the very folks who would be in line to pull down six-figure contracts if the measure passed, it turns out. According to campaign finance disclosure forms, a dozen entities offered large sums to the campaign, and all of them were construction, architecture or finance businesses. Of those 12 companies, seven are currently under contract with the district to perform Measure S-funded work. Another three have been pre-qualified by the district for future projects. And at least a few of these businesses had entered into contracts with the district — or been promised them — well before making their donations. (See accompanying infographic.)

If you're wondering how this is possible in California, where competitive bidding processes are mandated for just about all public projects, the answer is through what are known as lease-leaseback arrangements, which the district is using for almost all of its Measure S-funded projects. The financing arrangements allow school districts to skirt competitive bidding and hand-pick contractors and architects. The complicated approach to school construction has recently soared in popularity throughout Southern California, where districts have gravitated to it as a way to maintain more control over construction projects and — they say — give taxpayers and students more bang for their bond bucks. Tax payer leagues and others, meanwhile, argue that any strategy that gives district officials complete discretion over how to award millions of dollars in contracts opens the door to corruption, fraud and favoritism. Lease-leasebacks are relatively new to the North Coast, but they arrived just as their legality is being brought into question.

Traditional school construction projects follow a three-step process commonly known as design-bid-build. It's predicated on fairness, and, until recently, it's how nearly all the schools on the North Coast have been built and renovated. For that matter, it's the process — or a variation thereof — that nearly all governments across the nation use for large construction projects.

Under this approach, a school district must first secure financing. Usually this comes through a school bond, which allows a district to borrow a lump sum that's then slowly paid off by property owners within the district over the course of 30 or 40 years. Occasionally, a district comes into some money through other means — selling off an old school building or receiving a large donation. Whatever the source, once the district has cash in hand, it then hires an architect to plan out its project, whether it's a new building or renovating an existing facility. This is the design phase.

With plans from the architect, the district then looks for a contractor using a process mandated by the state. It advertises the project in the local paper of record and solicits bids from local contractors using the architect's plans. The contractors look at the plans and the minimum qualifications outlined by the district, then submit sealed bids to the district pledging to do the project for a certain amount (the bid phase). The district then unseals the bids and is bound to grant the contract to the lowest bidder, who then builds the project.

The design-bid-build process is set up to eliminate favoritism, fraud and corruption by taking the power to decide who gets lucrative contracts out of officials' hands and letting market forces dictate the outcome. The thinking goes that this guards tax dollars, making sure they are spent frugally, maximizing their impacts for schools and children.

In 1957, the California Legislature recognized that school districts had few funding options at their disposal. State law prohibited counties, cities and school districts from carrying any debt that exceeded the amount of a single year's revenue — meaning districts couldn't get a private loan to build a new school — unless they got the approval of 66 percent of voters. So, in situations where voters were unwilling to pass a bond or allow the district to take on a large debt, districts were stuck. The Legislature sought to open up a new avenue for school funding, and the lease-leaseback was born.

Outlined in the state education code, the lease-leaseback arrangement allows a district to lease its property to a contractor for a nominal fee — usually $1 a year. The contractor then finances and builds whatever project the district desires — say a new school — which it then leases back to the district for a monthly fee that covers both the financing and the construction. This allows districts to spread the costs of new building or renovation over decades and, once the final bill is paid off and the term of the lease is up, the property ownership reverts back to the district. But in creating this new funding avenue, the Legislature realized subjecting it to the competitive bidding process could become a nightmare for districts, leaving them to consider too many variables for a low-bid-take-all process to account for. So the Legislature made lease-leaseback construction arrangements exempt from competitive bidding requirements.

Lease-leasebacks seem to have been a little-used provision of state law until the mid-2000s, when school districts in Southern California began seeing the practice as a way to skirt competitive bidding, allowing them to hand-pick the people they want to work with.

- Photo courtesy of Eureka City Schools

- Fred Van Vleck

Sitting in Eureka City Schools' district office, Superintendent Fred Van Vleck said it's no secret that competitive bidding has its flaws. It ties the hands of the district, he said, leaving little flexibility to prioritize local — or even reputably good — contractors. "You just go with whoever the lowest bidder is," he said. "If Pierson is $1 more, then we go with Joe Schmo from San Francisco." Then there's what Van Vleck and Assistant Superintendent of Business Services Paul Ziegler dubbed "change-order queens," or contractors who bid low but then ask for additional money at every turn in the processes, whenever they find a flaw in the architect's plans or run into something unforeseen. And, if something goes really wrong with the project, Van Vleck said you can bet the architect and the contractor will point fingers at each other and everyone else; there's just no accountability.

Contractors often feel the same. Dennis DelBiaggio — who donated $5,000 to the pro-Measure S campaign and owns Ferndale's DCI Builders, which is slated to be the general contractor for bond-funded renovations at Alice Birney Elementary Schools — said lowest-bid projects have a trickle down effect. When bidding on a large project in Humboldt County, DelBiaggio said general contractors will usually all collect bids from the same subcontractors for plumbing, electrical work and other specialties. In a low-bid process, DelBiaggio said general contractors will feel obligated to take the lowest subcontracting bids, meaning general contractors will sometimes feel forced to lower their standards and work with subcontractors they don't like or trust simply because they fear a higher bid will cost them the job.

DelBiaggio said he thinks lease-leasebacks can provide a better value to districts, as they bring general contractors in earlier in the process — before plans are set in stone — and foster a kind of team approach. The district can tell a contractor what its budget is, and the contractor can find the best ways to work within that to deliver the project the district wants. And — especially in a small area like Humboldt — DelBiaggio said contractors know that if they take advantage of a district they're not going to get another lease-leaseback contract.

Van Vleck said accountability is a huge part of the lease-leaseback draw for him. He pointed to the upcoming modernization of the Eureka High gym as an example. Built in 1947, it's a mess, with electrical, seismic and accessibility issues that will cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $5 million to repair. He said it will be ideal to go through the gym with an architect and a general contractor and let them work together to find the best approach to repair it. They'd also then be forced to stand behind that approach, with less room for finger pointing. "With a project like that, we want someone we hold accountable," Van Vleck said.

Sitting in his law office in San Diego recently, Kevin Carlin explained over the phone the origins of what has at times seemed almost like a Quixotic quest against lease-leaseback arrangements. Carlin explained that he's a fiscal conservative, a "firm believer in the marketplace and open competition," who grew up in a family of construction workers.

When he became a lawyer and opened his own firm in 2006, Carlin primarily represented contractors and subcontractors on large jobs. Lease-leasebacks first appeared on Carlin's radar in 2009 and he said the concept never really sat well with him because the deals turned over taxpayer money but were negotiated in private and never competitively bid. That year he was serving as general council for the Associated Subcontractors Alliance of San Diego and filed a lawsuit in Oceanside challenging a lease-leaseback. The suit didn't go far, but it caught the attention of some big contractors in the area who shared their displeasure with the local subcontractor community. Soon, the alliance decided it would be best to part ways with Carlin.

A few years later, in May of 2012, Carlin said he was sitting at home reading the newspaper when he came across a story about a school district in San Ysidro that had just awarded an almost $4-million contract for a summer heating, ventilation and cooling system upgrade project. "I know what kind of work that is and there's no way this is more than a $2.5 million job if you put it on the street," Carlin said. "I thought, 'This is just wrong. ... I specifically remember that as the spark that lit this fire for me. I went and addressed the board during public comment and told them, 'I think you're overpaying and every dollar you over pay is one less dollar you have to spend on another project.'"

With the fire lit, Carlin said he started to realize that lease-leasebacks are widespread and ripe for abuse. "It's just growing like wildfire," he said. A series of Voice of San Diego reports in 2013 found a correlation between contractors who gave large sums to bond campaigns and those who were awarded lucrative contracts in 13 districts that used lease-leaseback arrangements (the correlation was 100 percent in four districts). A subsequent series of reports found contractor money seeping into school board campaigns as well. And lease-leaseback contracts were at the heart of scandals in San Ysidro and Sweetwater that saw district officials indicted for taking bribes, benefits and improper gifts from contractors.

"Anytime you introduce the possibility to deviate from the lowest sealed bid, you open the door to fraud, corruption, influence and favoritism," said Carlin, who's now spent much of the last three years challenging lease-leaseback deals throughout Southern California. Carlin has argued unsuccessfully in Torrance, Sweewater and Oceanside.

In June, however, he got a huge break in the form of a decision from the state's 5th District appellate court. Carlin had filed a lawsuit on behalf of Stephen Davis, a taxpayer who challenged a $36.7 million lease-leaseback contract under which the Fresno Unified School District built a new middle school. The superior court had granted a motion to throw out the lawsuit but Carlin appealed, and the appellate court issued a detailed 41-page ruling stating that it found reason to believe Fresno's lease-leaseback arrangement was illegal for a couple of reasons.

First, the court found that because the district had used the contractor — Harris Construction Co. — as a paid consultant prior to the lease-leaseback agreement to help design and develop project plans, the company had a conflict of interest and should have been prohibited from taking on the project it helped plan. "This prohibition is based on the rationale that a person cannot effectively serve two masters at the same time," the ruling states.

Second, the court found that to be valid, a lease-leaseback arrangement must align with the Legislature's original intent, meaning it must include a financing element for the project and a genuine lease that involves the district using the facility while leasing it from the contractor. Basically, the court agreed with Carlin that the district had entered into a "sham" lease-leaseback for the sole purpose of skirting competitive bidding.

Word of the court's decision traveled quickly through education and construction circles. Not only does the decision have the potential to set case law — or legal precedent — on lease-leaseback arrangements, but it also rendered Harris Construction's contract with Fresno illegal. In California, a contractor who enters into an illegal construction contract with a district can be made to repay the contract, even after construction is complete, meaning the ruling left Harris Construction staring at the possibility of being forced to repay $36.7 million to Fresno Unified.

The district immediately appealed the ruling to the state Supreme Court, which has yet to decide whether it will take up the case. Wary contractors throughout the state didn't wait to see what the court would do. Instead, they descended on the Legislature. After lobbying efforts by the Associated General Contractors of America, the California Coalition for Adequate School Housing and others, state Assemblyman Kevin Mullin and a group of co-authors gutted Assembly Bill 975, which dealt with pre-qualified contractor claims, and amended it as an urgency bill that would retroactively make lease-leaseback agreements legal and unassailable in court. As the Journal went to press, the bill had stalled in committee and appeared unlikely to be taken up before the Sept. 11 end of the legislative session. But it's clear the Fresno case got lots of people's attention.

For Carlin, it offers some vindication. "I'm doing this because I'm passionate about it," said the former philosophy major. "This has not been a profit-making career for me, but I knew that going in. I believe in this, and the Davis decision brings some good sanity and common sense back to this thing."

Eureka City Schools is not the first district to use lease-leasebacks on the North Coast. McKinleyville Union School District is currently unveiling a gym and multi-purpose room at McKinleyville Middle School, a $2.7 million project built in a lease-leaseback arrangement. Back in 2012, Southern Humboldt Unified School District entered into a lease-leaseback for construction projects at Redway Elementary and South Fork Junior High. And Eureka City Schools even has some prior experience, having used a lease-leaseback to complete the first phase of renovations to Lincoln School.

Fortuna-based Dinsmore Construction served as the general contractor for all these projects, and is currently on the second phase of work at Lincoln under a $1.1 million lease-leaseback contract entered into after the company's $5,000 campaign donation helped Measure S pass. Owner Dirk Dinsmore hadn't responded to Journal calls seeking comment by press time.

Sitting in a small conference room in the district office, Superintendent Van Vleck and Assistant Superintendent Ziegler said they are aware of the court decision in Davis v. Fresno Unified and are watching the situation closely. But they had a much different take on the ruling than others. "The court affirmed it's legal," Ziegler said. "The question is: How much can a contractor work with a district in advance?" Van Vleck chimed in, "We've never paid a contractor to do a preliminary services agreement," he said.

For Eureka City Schools, this could be an important distinction. Back in 2012, the district entered into preliminary services agreements with Dinsmore Construction and DelBiaggio's DCI Builders to help come up with plans for work at the Lincoln and Alice Birney campuses, respectively. Now, three years later, Van Vleck said the district never actually worked with DCI Builders under the agreement. "No money ever exchanged hands, and we haven't even really talked about the project," Van Vleck said, adding that the school board recently canceled the preliminary services agreement and decided to move forward with a lease-leaseback agreement with the company.

DelBiaggio said plans weren't complete for the Alice Birney project when he met with the district two or three years ago to discuss it, but he said he didn't have too much input on them, mostly because the project is pretty straightforward. The Journal didn't ask DelBiaggio specifically about the preliminary services agreement with the district because we didn't yet know it existed, and subsequent messages have gone unreturned. But DelBiaggio did say the district committed the Alice Birney project to him at least a year and a half ago, and that he donated to the Measure S campaign — in part — hoping the bond would pass and the project would be funded.

When it comes to Dinsmore Construction, it's a bit more complicated. No money exchanged hands under the agreement, but Van Vleck said the company did consult with the district about the first phase of modernization and upgrade work at Lincoln, which Dinsmore recently completed. But Van Vleck said that agreement didn't include the second phase, which Dinsmore is currently working on.

The question of how much input a contractor has on plans that he or she will ultimately enter into a no-bid contract to execute is a huge one, according to Carlin. "This is like hiring a fox to guard your henhouse," he wrote in an email to the Journal. "No matter how nice and reputable the fox, it's common sense not to hire a fox to guard your henhouse."

But the whole preliminary services question might not matter when it comes to Dinsmore, according to Carlin, who reviewed the district's contracts with the company at the request of the Journal and said he has no question the agreement is a "sham" lease-leaseback, not much different from the one he saw in Fresno.

In its recent ruling, Carlin said, the appellate court made clear financing is a key component of any valid lease-leaseback. In the Dinsmore contract, there's no genuine financing component, he said. Under the agreement, the district pays the company monthly for work performed — payment amounts have fluctuated from $80,000 to more than $330,000. The fact that the district voted in July to transfer more than $1.1 million from its reserves to help pay construction costs until bond revenues started rolling in (the district didn't receive its first bond funds until August) also can be seen as "irrefutable proof" that there's no contractor financing element involved in the project, Carlin said.

The contract does provide for six months of $5,000 payments to Dinsmore Construction after the project is complete, nominally fulfilling the leaseback requirement as laid out in the Davis ruling, but Carlin was skeptical as to whether this would be "legally sufficient."

Van Vleck, who came to Eureka in 2012 from Ceres, California, where he served as an assistant superintendent of business and oversaw some $150 million in construction projects, made clear in talking to the Journal that his district's needs are great. "The unfortunate reality is $50 million isn't a whole lot," he said, adding that it's probably only enough to fund about one-third of the projects the district needs. "We've just got a lot of buildings that have gone way beyond their useful life."

It's through that lens, Van Vleck and Ziegler said, that they are evaluating projects, contractors and construction methods, constantly looking for the best return on investment for students. But the reality is school construction projects are expensive — with prevailing wage requirements and oversight from the division of state architects — and they said they're going to look at all legal avenues to save the district money. To that end, they point out, the district opted not to hire a construction management firm — a third party to oversee the construction projects — and instead decided to act as its own agent, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Van Vleck admitted mistakes were made with the 2002 bond, but he said that can't be a part of the current discussion. "Despite the mistakes made in the past, we need to take care of today's students," he said. "You can't hold the students in classrooms now responsible for what was or was not done back in 2002."

It's been only nine months since a slim margin of voters passed Measure S, which was sold to them by the very businesses that are now profiting from their tax dollars. Few would dispute that many of the district's properties are in dire need of upgrading and repair. The question is, a decade from now, will district leadership be pointing at privately negotiated contracts, the legality of which has already been called into question, and talking about the need to move on from past mistakes?

Scheduled Bond Projects:

- Replace playground equipment

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Remove portable classrooms

- Modernize restrooms

- Construct student drop-off areas

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Alterations to community reception area and nurses office

- Construct a new three-classroom portable building

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Construct student drop off areas

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Construct student drop off areas

- Add additional parking

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Alterations to community reception area and nurses office

- Construct student drop off areas

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Add security cameras

- Create a career and technical education classroom

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Modernize the science lab

- Repair dry rot in gymnasium

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Add security cameras

- Reconfigure S Street entrance

- Create a career and technical education classroom

- Modernize the science lab

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Replace two portables with a new classroom building

- Modernize Ag and auto shop, classrooms and restrooms

- Modernize the band building

- Modernize the gymnasium and attached building

- Upgrade electrical system and replace windows in main building

- Modernize science building

- Install new security cameras

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Add security cameras

- Add teaching walls in all classrooms

- Upgrade PA/bell systems

- Modernize the multi-use room

- Complete Phase 2 modernization

Comments (4)

Showing 1-4 of 4