Raise your hand if you think you can solve an eighth grade math problem. If you came up during the learn-and-burn era of teaching in the 1990s and 2000s in California, you are familiar with filling in bubbles and teachers encouraging you to guess if you don't know the answer; cramming dates, vocabulary or formulas before the test and forgetting them the next day. In California, and throughout much of the U.S., that method is on its way out. If you're under the age of 18, from here on out you're going to have to explain yourself.

American views on education are constantly shifting and evolving. Emerging out of the high-stakes era of No Child Left Behind is a new national and state focus on critical thinking called Common Core. Surging along with it is a new vision of standardized testing and a series of overhauls trickling down from the state to local schools.

The implementation of Common Core is a long, complicated process involving a slew of state and federal education agencies, as well as local school districts, administrators, teachers and, of course, the students themselves.

Common Core is a nationalized standard measure of what students should be able to accomplish at the end of each grade year. In that sense, it's not so different than previous iterations of nationalized standards. Focusing on math, language and literacy, the expectations are intended to identify areas where students struggle and to make it easier for children who move from one region to another to pick up where they left off.

And it's been almost a decade in the making, according to Tina Jung, an information officer with the California Department of Education. "We've been talking about it for a long time," she said, adding that it's been 15 years since California's education standards have been updated. That's a long time, when you consider the brisk pace at which technology, communication and information have developed since the turn of the millennium.

Officially launched in 2009, the effort to get national adoption of Common Core was led by education officials and governors from 48 states. They were motivated to replace a hodgepodge of learning standards that every state in the nation had adopted independently by the early 2000s. "Every state also had its own definition of proficiency, which is the level at which a student is determined to be sufficiently educated at each grade level and upon graduation," Common Core's website reads. Forty-three states (and the District of Columbia, four territories and the Department of Defense) have adopted the voluntary standards.

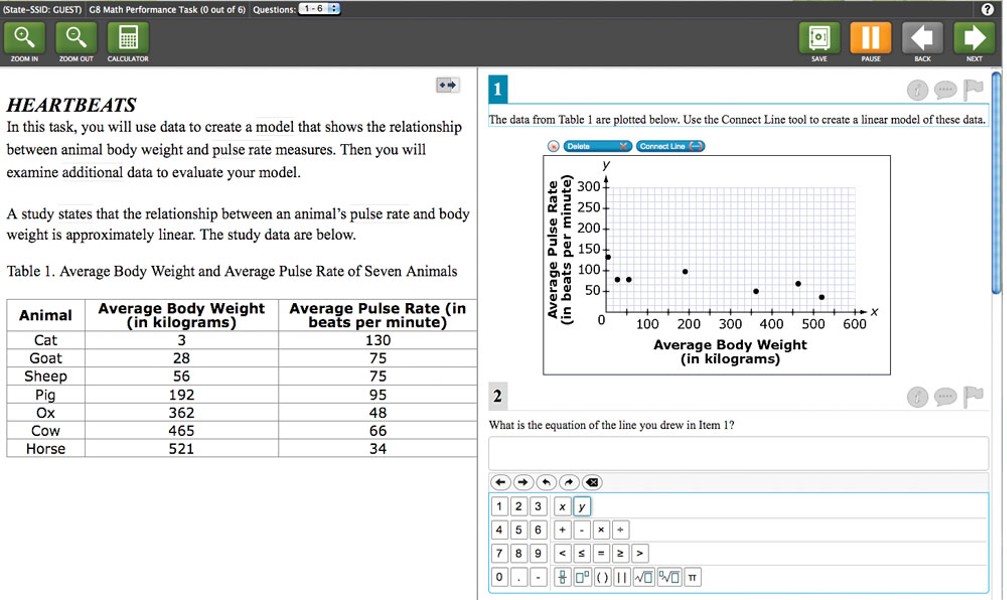

But Common Core is different than previous standards in what it expects of students. Beyond just knowing the answer to a math equation, for example, students are expected to know why it's the right answer. And they must be able to explain their answers in writing. The goal, according to the standards, is "more focused and coherent" teaching that leads to fluency in math — not simply the right answer to a problem.

"Common core is an initiative that's really going to help kids with achievement," said Lori Breyer, the Humboldt County Office of Education coordinator of school support and accountability. The standards, Breyer said, were developed by educators looking at what skills students need to be college- and career-ready when they graduate high school. "They determined what that looked like and mapped the standards backwards all the way down to kindergarten," she said. Keyboarding, for example, was typically a standalone ninth-grade course. Now, students are at least becoming familiar with technology in many subjects at the kindergarten level.

Freshwater Elementary School Principal Si Talty said Common Core is all about "the ability to process information using critical thinking."

Talty, three Freshwater teachers and Breyer gathered around a horseshoe shaped cluster of tables on a recent bright but foggy Friday morning. It was the third day of planning several staff members had agreed to take part in. Coffee in hand, laptops plugged in, they talked about how to best adapt their teaching styles and materials to the Common Core standards, and how to help other teachers grasp the changes that need to be made. "Teachers teaching teachers," Talty said. While larger districts may have curriculum specialists to help teachers adjust to new standards, small schools like Freshwater (and many others in Humboldt County) have to figure it out on their own. And collaborating and problem solving — much like what kids will be expected to do under Common Core — has been effective for teachers as well.

"It's been really powerful, it's moved us forward," said Freshwater sixth grade teacher Kylah Rush. "It's good for us to teach — to be uncomfortable, too. I think that's what I'm most excited about: Evaluating the ways kids solve different problems."

Are kids uncomfortable? Freshwater did a half-rollout of Common Core during last school year, and students were remarkably adaptable, according to the teachers discussing it that morning.

Second grade teacher Lynn Liebig said getting students who were used to working independently on workbooks to discuss and debate schoolwork in the classroom was "rough at first." But, "as they got used to that, they really embraced it and tried to outdo each other," she said.

The Common Core standards — the actual expectations of students at each grade level — are comprehensive. In mathematics, it's suggested that teachers not only stress conceptual understanding of math, but keep returning to "organizing principles such as place value and laws of arithmetic to structure those ideas."

"There is a world of difference between a student who can summon a mnemonic device to expand a product such as (a + b)(x + y) and a student who can explain where the mnemonic comes from," the standards read. "The student who can explain the rule understands the mathematics, and may have a better chance to succeed at a less familiar task such as expanding (a + b + c)(x + y)."

Teaching kids the fundamentals of patterns starting in kindergarten, for example — and returning to those fundamentals in subsequent grades — will prepare students for algebra later on, said Shannon Morago, a math and science teacher at Six Rivers Charter High School and program director for the Humboldt State University School of Education.

And while Common Core doesn't dictate how teachers will teach the concepts, it does lay out specific benchmarks for students at each grade level. In fifth grade, for example, students should "develop fluency" with addition, subtraction and multiplication of fractions and develop an understanding of volume, among other things. High school standards aren't separated by grade, but by conceptual categories, giving expectations for students in advanced courses such as calculus, but assuring that students in lower level courses understand the concepts that Common Core suggests are necessary for college and career success.

The standards also set out goals for language and literacy, focusing on writing, reading, speaking and listening as well as proficiency in history, social studies, science and technical subjects. They suggest that teachers focus more on nonfiction than fiction texts and don't encourage the grade-by-grade accomplishments that Common Core's math standards do.

Teachers are tasked with redesigning their curriculum to fit Common Core standards. There will be less focus on memorization, and more time spent making sure students understand why the fundamentals work.

Sunny Brae Middle School Principal Lynda Yeoman said newer teachers are having a slightly harder time adapting to the standards, saying "vets" like her "don't see standards as being that different than the way we implemented education before the California state standards moved us into an era of more 'drill and kill,' more memorization of facts and away from the thinking process."

"For teachers who are newer — only since California standards were put in place — [Common Core] is very different," Yeoman said, adding that most teachers of all experience levels seem excited. "I think all really good teachers are happy about it," she said, and "everybody agrees if you're going to compare schools and assess schools across the nation, you have to have standards."

Morago, the program manager for HSU's education department, said brand new teachers may have an advantage; HSU has been incorporating Common Core standards into its credential program for the last three to four years. Tomorrow's teachers are being prepared for not just the content standards, but the new methods and practices expected by Common Core — an asset current teachers don't have.

At the same time, Morago said, credential students sometimes express concern about their own understanding of the math and science fundamentals that they will be expected to impart to their students. "They're products of the No Child Left Behind education system and ... they sometimes feel their content knowledge isn't what it should be," she said. "We have to close that loop."

A small, rural county with many diverse school districts like Humboldt sees some of the trickier adoptions of Common Core and the new standardized testing.

John Sutter, the former superintendent of Orick School (he accepted a job at Loleta School District this school year), said a single classroom at Orick contains students of multiple grades. "It's pretty tough to get all the standards — well it's impossible," he said. But the faculty is trying to integrate the math and science standards, he said, describing a hot air balloon project designed by his former colleague Matt Ross that allowed students of various levels to pitch in. "They built the balloons, of course, and that was engaging," Sutter said, but first they had to calculate the volume of hot air required to lift the objects. Then explain how and why x amount of hot air can lift y amount of mass. "That's kind of how we're approaching it. That way we get a broad range of standards in one compelling project."

Morago said science standards used to be very specific, saying things like "students will know that evolution is the change in traits over time," she said. "Now they're very different — they're performance-based."

For example, students are expected to be able to create a model, or design a solution to an environmental problem caused by humans. It's a focus on engineering that Morago is excited about, but it's a philosophy of Common Core that has highlighted a political rift in the standards' adoption. Indiana backed out of Common Core standards earlier this year, decrying a federalized standard, and Arizona's superintendent of public instruction just this month flip-flopped on his Common Core stance, calling some of the standards' literature recommendations "absolute pornography" and science standards "'indoctrination standards' that teach man-made global warming," according to the Arizona Capitol Times.

The California Legislature approved the Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) program in 1997, which assessed students in second through 11th grades on a variety of subjects by having them answer multiple choice questions toward the end of each school year. Later, a writing component was added for older grades, and other changes were made through the years until the STAR program became inoperative in 2013. The test results were used to rate California schools by both state and federal accountability measures.

Jung, like many involved with California's adoption of Common Core, is thrilled. Before this last year, California had its own accountability model for schools, in addition to a federal accountability model — part of the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, she said. During the last decade, federal scores showed schools in California declining, while the state model showed scores steadily increasing. "How can those both be true?" Jung pondered, adding that the previous model of standardized testing wasn't likely effective or accurate. "That's perhaps why the No Child Left Behind Act has not been reauthorized by the federal government," she said. Now there's a "bridge program" between the state and federal models, and in the next several years, a new standardized testing program will be in place: the Smarter Balanced Assessments. (Take a Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium sample exam here.)

These new tests don't have everyone thrilled. In fact, a think tank called the National Center for Fair and Open Testing complains on its website that new tests will cost states more and suggests that "harder tests do not make kids smarter." While implementation of technology for Common Core and the SBA testing is indeed costly, teachers and administrators say that's simply the price of coming up to speed with today's technology demands. And while new forms of testing mean new challenges, supporters say changes to Common Core and testing embody a new way of teaching — not simply harder testing.

California has invested $1.25 billion in Common Core implementation, giving schools money to purchase technology, train teachers and update educational materials, such as books. Humboldt County schools received $4.2 million for implementation, and while that money is for Common Core Standards, not SBA testing (Jung is quick to point out that they are separate programs), many Humboldt County schools spent a good portion of their funds on technology improvements that will also ensure that schools can test properly.

This spring, California schools went through a trial run of the new testing, and there's palpable relief among the teachers and administrators who described the process.

Yeoman, the Sunny Brae principal who has also been tasked with coordinating the Arcata School District's testing, said that, despite a few early glitches, this spring's testing went well. It's up to schools and their districts to administer the tests — which are all taken online. That means every student must have access to a computer, which for many school districts means creating a schedule to get students in and out of the computer labs within the six-week time frame allowed for testing. "Our district was very proactive about that," Yeoman said. "We planned ahead for increasing bandwidth, we put computer labs in the schools."

Both Common Core standards and the new standardized testing mean schools must have strong technical support.

Sutter, formerly of Orick School, has heard stories about other rural schools around the nation having to bus kids to testing centers. But Orick and other Humboldt County schools were able to avoid that disruption by investing in upgrading schools' technology. Orick School even provides a Wi-Fi hotspot to the community. "I was pleased the state gave this trial run," Sutter said. "That showed a lot of wisdom."

Yeoman's takeaway from the trial testing is that practice tests work because kids need to familiarize themselves with the practical challenges of the test. "There's nothing worse than a student missing something because they don't understand how to use the calculator, for example," she said. "It's really making sure that kids are familiar with computers and their programs and structure."

In the end, though, today's students are adaptable to new technology — more than some teachers, even. "We were far more intimidated by it than they were," Yeoman said.

Rush, from Freshwater Elementary, is excited about the change in testing along with the Common Core implementation. "It's shifting away from high-stakes testing," she said. "The test has its challenges, but it's so much more interactive."

Jung, of the state board of education, winces at the mention of "teaching to the test," which she says was never really the case. "Schools perform well because they want to perform well," she said. Financial benefits for schools that perform well on standardized tests went away with the financial crisis of 2008, she said, and while there remain competitive grants that schools can apply for, the only direct benefits schools get from performing well are honorary awards such as being named a "distinguished school," which can be good for a school's public imagine and may attract students. "Teachers don't teach to the test," she said. "They never have and they never will. In the olden days there were lots of accusations — it may appear that way, but they don't do that. There's never been a monetary award associated with doing well."

But Morago said previous standards, and the testing to evaluate how schools were meeting those standards, had kids "regurgitating" facts. That doesn't help students build "a coherent idea of an interdisciplinary world," she said. And that's the "lofty goal" of Common Core and the new standardized testing.

Yeoman said she's never focused on teaching to standardized tests. "I think you have to teach children and if you do a good job teaching children, you'll do well on the standards," she said. "And it's worked so far." Jung said the California Department of Education is preparing an assessment of last school year's trial testing that it will present in November. But schools are receiving very little information from the results of those tests, which has been frustrating to some administrations.

Tish Nilsen works for Eureka City Schools and is in charge of instructional coaches, who help teachers develop and refine curricula. She said the only information her district will be getting back from the state is scores from the fifth, eighth and 10th grade science exams, as well as results from the high school exit exam.

"We're not going to really see any major changes or have much to go on if students get better on language or math until 2016," she said. "2015 will be our baseline year. You always want to be able to look and see how your students are performing ... because we have some phenomenal teachers. It's frustrating not to be able to see the results of the hard work."

Still, Nilsen was excited about the change and praised her teachers that are embracing the new standards. Morago, HSU's education department program manager, said criticism about the federalization of school standards is unfair — it was developed under the guidance of state education officials. There is, however, one group noticeably absent from the standards' development, she said. "Anytime there's a development of the standards this probably happens," she said, but "I'm not sure there's anywhere ... that [Common Core standards] were developed with the voice of students. Relevance really impacts how students perform and are motivated in school. It is definitely another way that adults are imposing development on kids."

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Common Core implementation on the North Coast has been its broad support. Despite some nerves and glitches in rollout, there seems to be a profound excitement among teachers and administrators and a spark in students in these first stages of the change.

"It's going to really help our kids think, it's going to really help their thoughts and judge what they're learning," Nilsen said. "It's one thing to say, 'Two plus two equals four,' but it's another thing to explain why two plus two equals four."

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1