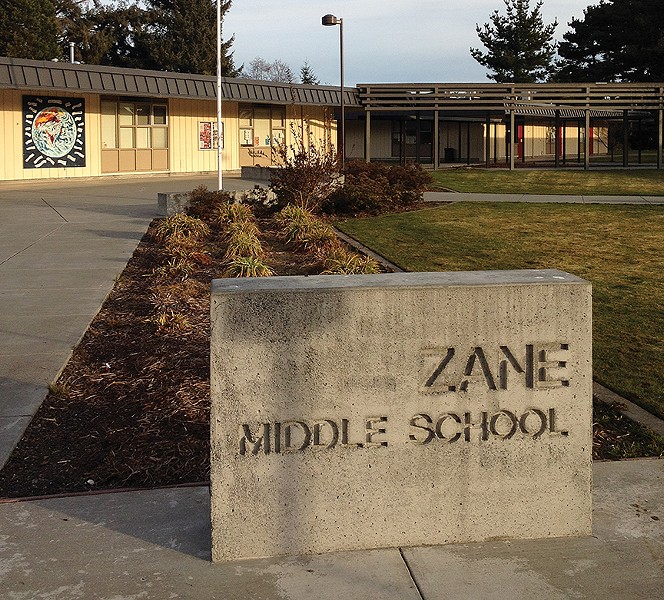

Brianna sits at her kitchen table, surrounded by manila folders spilling notes she's taken about her struggles with the staff and administrators of Zane Middle School over the treatment of her 13-year-old daughter Jessica.

"This is not a black or a white thing," says the lanky, kind-eyed single mom who works full time, coaches her daughter's volleyball team and says she never expected to be a plaintiff in a discrimination lawsuit against her daughter's school district.

The notes document a year and a half of merciless bullying — students calling Jessica "nigger," "hooker" and "whore," shoving her head inside a locker, smearing her face with makeup and tripping her in the hallway. Calendars made with Excel spreadsheets and printed on computer paper are filled with notes about emails sent, phone calls made and meetings attended as Brianna tried to get the harassment to stop. Eventually she came to the conclusion that it wasn't going to stop because the school's administrators simply weren't taking the problem seriously.

So Brianna started working with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, which began investigating racism and sexism at Eureka City Schools about a year ago following a call to its complaint hotline from a grandma who was desperate to help her bullied grandson.

On Dec. 18, the ACLU, in conjunction with the National Center for Youth Law, filed a federal civil rights lawsuit alleging "years of intentional discrimination" by the Eureka City Schools District, discrimination based on students' race, sex and disability status. In a 51-page complaint submitted to the U.S. District Court in San Francisco, lawyers for the two groups outline "a racially and sexually hostile environment" at the district's schools, which include four elementary schools, two middle schools and two high schools. The suit alleges that staff and administrators discipline minority students more harshly than white students, make racially ignorant and sexually offensive comments in class, offer curriculum that affronts or ignores cultural history, and fail to prevent widespread racial and sexual bullying.

The specific accusations are incendiary and disturbing. The suit describes an environment where students regularly pinch and punch girls' breasts on "Titty-Twisting Tuesday" and smack each other's behinds on "Ass-Slap Friday"; where a teacher once told students that "black people get bored easily" and ordered a teenage girl, "Don't give me your black attitude"; where an administrator told a mom that she'd have to prove her daughter had a learning disability, at her own expense, before she'd be helped; and much more. The suit says this hostile environment has led to anger, depression and anxiety for at least four Eureka students, the plaintiffs in the case, whose grades have suffered and who are now afraid to go to school.

The lawsuit asks the district for a declaration acknowledging that it has violated the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, to pay attorneys' fees and unspecified monetary damages to the plaintiffs and to implement a range of administrative fixes, including training programs, better data tracking and monitoring to ensure things improve.

Jory Steele, managing attorney for the ACLU of Northern California, says the issues extend beyond Eureka — that they're "a Humboldt County problem." On the same day it filed the lawsuit, the ACLU, along with the National Center for Youth Law and California Indian Legal Services, submitted a letter to the United States Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights asking for an investigation into Loleta Elementary School. The letter alleges discrimination based on race and disability as well as lopsided discipline and abuse, both physical and verbal, of Native American kids.

Perhaps the worst perpetrator of these crimes, according to the letter, is the school's principal/superintendent, Sally Hadden, who allegedly kicks students in the butt, smacks them on the head with a clipboard and once grabbed a Native American student by the ear and said, "See how red it's getting?" The letter was filed on behalf of the Wiyot Tribe and members of the tribal council of the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria.

In response to the suit, Eureka City Schools Superintendent Fred Van Vleck issued a press release declaring in no uncertain terms that the district does not tolerate harassment or intimidation. He said the district is actively investigating but that "at this time we are not aware of evidence to support the allegations."

In a follow-up phone call, Van Vleck said the lawsuit took the district by surprise. "The parents never filed any formal complaint against the district or initiated any formal complaint process to allow us an opportunity to start working on some sort of resolution to this short of going through the lawsuit," he said.

Back in her kitchen, Brianna sits surrounded by a paper trail that says different. She says she made at least 30 separate complaints to school administrators and met regularly with Zane's principal and vice principal. "Brianna" is not her real name, nor is her daughter named "Jessica." The plaintiffs and their legal guardians have been given pseudonyms in the lawsuit to protect them from retaliation — though Brianna says Jessica's tormenters have been calling her a "snitch" for months.

The defendants named in the suit include the district, its superintendent members of the district school board and the principals and vice principals of both Zane Middle School and Eureka High School.

"This is not a black or a white thing," Brianna repeats. "It's not about money. It's not about anything other than change. Make schools safe — free from humiliation and intimidation. Make sure school is safe for all kids: black, white, Mexican, Asian, Indian, it doesn't matter. Girls, boys, gay, lesbian, it doesn't matter. Make school a safe place."

After the ACLU received the call from a worried Eureka grandma, members of the group's northern California office in San Francisco drove up to see if discrimination was a broader community issue. "And we discovered that it was," says Steele, managing attorney for the group. She and her colleagues arranged a community meeting at the Boys and Girls Club on J Street in Eureka, notifying families through local community groups.

"When the tribes and my organization heard the ACLU was coming up, we ran to that meeting," says Delia Parr, directing attorney for California Indian Legal Services. She and tribal leaders had been hearing for years about discrimination against Native American students at Loleta Elementary. (See "Taking Charge in Loleta," Dec. 13, 2012.)

Roughly 40 people showed up to the meeting on a cold January evening. "They were all extremely passionate, and they were upset," says Steele. "And all had similar versions of the same story."

That story goes something like this, she says: A parent or guarding makes a complaint — about bullying, discrimination, racially disparate discipline, inappropriate comments or curricula, etc.; school administrators downplay or minimize the problem, or address it insufficiently; and the behavior continues.

Michael Harris, senior attorney at the National Center for Youth Law, uses the example of "Titty-Twisting Tuesdays" and "Slap-Ass Fridays." The abusive tradition has been going on for at least two years at Zane and Eureka High, he says, and teachers are well aware of it.

"Indeed," the lawsuit contends, "students have gone so far as to assault staff; students have slapped the buttocks of school administrators and female teachers, and Defendants have failed to take steps to stop this behavior."

Female students have taken to wearing rhinestone-encrusted jeans as armor, rather than a fashion statement. Brianna's daughter, Jessica, has resorted to changing clothes in the locker room's toilet stalls to avoid being smacked. And like other moms, Brianna says she's complained numerous times to no avail.

In fall 2012, Jessica asked her science teacher about the purpose of a structural support pole in her science classroom, and, according to the lawsuit, he told her the poles were "for pole dancing" and then did his own impromptu dance. "The teacher laughed when Jessica K. became visibly upset," the suit says.

"This is a 12-year-old girl," Harris says. "She was freaked out about it. And the district didn't think that was creepy, so they didn't do anything to the teacher. It sends the message that terrible things are going to happen, and if you complain the situation is not gonna change."

Brianna says the situation has changed her daughter's demeanor: "Jessica is a really happy kid. She's always been a happy kid. But once this began happening she just pulled back. She would cry at night. She became withdrawn. She began to pick her fingers to the point where blood was coming out. She was a complete nervous wreck. And she was afraid to go to school."

Brianna says that she's been told repeatedly that the problems are exclusive to her daughter. Other parents in the district have heard the same excuse, says Steele. "We've been up here many times since January. ... We've talked to many families and many people in the community on many different occasions." Jessica's experience is not unique, Steele says. While only three moms and one grandmother chose to become plaintiffs in the suit (along with their children/grandchild), they represent a widespread problem, according to both the lawsuit and the Loleta letter.

Van Vleck, the Eureka district's superintendent, finds this hard to believe. "I can tell you that I personally have two children who attend Zane, and I've had multiple conversations with them," he says. "And this certainly is not something that has been an issue that has arisen with them." Asked if his kids are white, he says they are.

Regardless, Van Vleck says the lawsuit is overkill. There's an official complaint process posted in every classroom in the district, he says. "So it's not like it's buried someplace where nobody would ever see it. There's an actual form to fill in, and that triggers a process that we're required to follow." The plaintiffs failed to follow that process, he says.

Brianna disagrees. She says she and her daughter complained dozens of times, and whether or not those complaints followed the exact rules of the official complaint process, school officials have been aware of the problems for a long time and have not taken sufficient action to solve them. "I am not litigious by nature," she says. "I think that if I can talk with you and interact with you then we can settle things." Because of this conviction, Brianna didn't attend any community meetings with the ACLU, she says. But after her own problem-solving efforts failed, she joined the suit.

Jessica's classmates have repeatedly told her that she must live on S Street because black girls grow up to be strippers, or H Street because they become hookers, or W Street for whores, Brianna says. When Jessica was laughing in the hallway one day, one of her main tormenters said, "Finally, the nigger is happy," Brianna says.

The lawsuit is filled with similar episodes. When plaintiff "Anthony J." was in sixth grade at Alice Birney Elementary, for example, students regularly called him "nigger," made monkey sounds at him, threw food at him, hit him and spit on him, the suit alleges. This abuse has made him "withdrawn, depressed and angry" to the point of suicidal thoughts. While still in sixth grade he allegedly told his grandmother, "I should just shoot myself in the head."

"Ashley W.," another plaintiff, heard her fellow Zane students say "nigger" or "nigga" as much as 20 times per week, often directed at her, the suit alleges. She, too, has paid a psychological toll, suffering headaches and insomnia, according to the complaint.

The fourth student plaintiff is "Alexis R.," a 16-year-old Yurok Tribe member who has been bounced from Alice Birney to Winship Middle School, Zane, the county-operated Eureka Community School and now Eureka High. The lawsuit alleges that Alexis was inappropriately shuffled off to the educationally inferior community school because of her race. Native American students are pushed into community schools at a higher rate than white students, often for inappropriate reasons, according to both the Eureka complaint and the Loleta letter. The suit says such schools are intended for "high-risk" students — those who have been expelled or referred by the probation department, for example — not students like Alexis, who was behind on her credits but had no disciplinary issues.

Jim McQuillen, director of education services for the Yurok Tribe, says getting transferred to community schools has serious long-term effects. "There's that pipeline from school to prison, so to speak," he says. "Once you're in that system of alternative or disciplinary-type programs there's a higher chance of ending up incarcerated. And once in, it's difficult to get out."

In the 2011-2012 school year only 15 of the county's 136 Native American high school graduates completed their "A-G coursework," meaning the classes necessary to get into a California State University or University of California school. In other words, just 11 percent of Native American graduates could get accepted into a four-year college in the state, less than half the countywide average of 25.5 percent. Last school year was even worse, with just 14 of 139 Native graduates (10 percent) completing college-level coursework. Black and Native American students also have higher dropout rates than the county average.

Some blame the struggles of Native American students on their upbringing and home environments. McQuillen says there's responsibility on all sides — "parents, families, definitely the system." But he added that it's important to look at the issues in the context of a cultural history that includes massacres, disease, relocation and exclusion from local public schools.

That history is neither understood nor respected in Loleta or Eureka, according to the complaints. Last spring at Eureka High, Alexis R.'s history teacher asked students in her class to raise their hands if they were Native American, according to the lawsuit against the district. When Alexis R., who is Yurok, raised her hand, the teacher allegedly asked her to explain the 1860 massacre on Indian Island in Humboldt Bay, which was perpetrated on an entirely different tribe, the Wiyot.

Another Eureka High teacher allegedly "had her history students 'make up' different Native American tribes and then pretend to fight each other" because, according to her, "this was how Native Americans traditionally resolved conflict between their communities," the lawsuit states.

The suit also claims that Eureka City Schools administrators have "routinely" refused to excuse Alexis' absence "to participate in vitally important Yurok cultural activities, including community brush dances, funerals, and salmon fishing."

Matthew Mattson, executive director of tribal operations for the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, says the tribal council has had a difficult time deciding how to address the problems in Loleta. He says the tribe has worked with the school and the community to effect cultural change at Loleta Elementary. And the tribe was reluctant to take any moves that could be seen as adversarial.

"The tribe is trying so hard to reconnect with its culture and to try to overcome historic trauma that's been building up for generations," Mattson says. But the tribe ultimately decided that an Office of Education investigation "may be the shock to the system that's needed to try to get to some results," Mattson added.

Could a lawsuit be on the way in Loleta, too? Mattson hopes not. "We're cautiously optimistic that this [letter] will generate results, dialog and some sort of settlement without having to go to the level of a lawsuit," he says. But the tribe is prepared to support a suit if all else fails, he adds.

In discussing the allegations, Mattson occasionally pauses to say he can hardly believe we're talking about these issues and seeing this type of systemic discrimination here at the dawn of 2014 in California, one of the most progressive places in the world. "It just needs to stop, and somebody has to stand up and bear witness," he says. "It may be uncomfortable for all of us as a community ... but it needs to be talked about — openly and publicly. We need to find solutions."

Comments (18)

Showing 1-18 of 18