Oregon State University biologist John Chapman can remember the exact moment his scientific world was turned upside down. It was June 5, 2012, and he was standing on Agate Beach, just 5 miles from his Newport home, staring at a large dock that had washed ashore.

The 66-by-20-foot platform had been ripped from its mooring some 4,500 miles away, one of countless pieces of debris swept into the sea by swirling surges when a devastating tsunami slammed into the coast of Japan following a magnitude-9 earthquake in March of 2011.

Now, 452 days after the harrowing event that took thousands of lives and destroyed entire towns an ocean away, Chapman stood face-to-face with a towering piece of the aftermath.

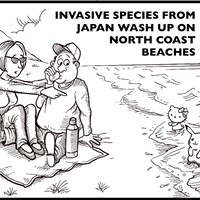

Here was confirmation that a massive remnant from the Japanese tsunami could make its way to local shores, but that's not what gave him pause. What caught Chapman by surprise were the passengers. There in front of him were far more than just a token cluster of barnacles or clumps of straggly mussels stubbornly clinging to the concrete hull — instead there were dozens of species, including crabs and sea stars.

They were alive. And, he knew instantly, they weren't from around here.

"I was in shock for at least an hour," says Chapman, a regional expert in invasive marine species. "I just couldn't believe it."

Before that day, Chapman says, he never would have thought those sea creatures, some delicate and others hardy, could have made the long journey. The scientific consensus up until then was that such lengthy migrations were impossible — the ocean expanse was too massive and the harsh conditions at sea too severe for marine life to survive for months or even years on end, aimlessly drifting for thousands of miles on the currents.

"It was," Chapman says, "like looking at a spaceship."

But here they were. Not only had the critters survived, but the wayward travelers were flourishing. A barrier was broken. Or, at least, scientists began to realize the invisible hurdle of time and distance could be overcome.

"Up to the minute we found that first object that was colonized, we thought that it was impossible," Chapman says. "In science, when find out you are black and white wrong, you steer right toward it."

The dock's denizens would prove to be anything but an anomaly.

In fact, nearly 300 species were found to have made their way to North America and Hawaii between 2012 and February of 2017, according to new research by Chapman and a team of other scientists, who tracked 634 pieces of tsunami debris — including a skiff found near Dry Lagoon in June of 2015 — over the five-year period.

The North Coast's best-known piece of tsunami debris and the first confirmed California find — a 20-foot boat from Takata High in Rikuzentakata found on a Del Norte County beach — was not included but photos show only gooseneck barnacles onboard.

Sea stars, two kinds of fish, snails, jellyfish, crabs and sea slugs, "none of which were previously reported to have rafted transoceanically between continents," were among the stowaways, according to the results published in the Sept. 29 edition of the journal Science.

"It is surprising that living species from Japan continue to arrive after nearly six years at sea, four or more years longer than previous documented instances of the survival of coastal species rafting in the ocean," the Science paper on the research states.

The key, scientists found, could be summed up in just one word: Plastics. Unlike wood or other traditional building materials, which would eventually disintegrate, many human-made elements can stay afloat, creating a sort of life raft to ferry creatures in a way that would not have been possible a generation ago.

"Basically, anything that could get on a hard object got a ride," Chapman says, adding that some of the species that landed on the debris might have scurried away or escaped in the water before scientists were able to get a look at them.

Throw the expanding development along the world's shorelines in with increasingly stronger storms being generated by climate change and a recipe for an unprecedented intercontinental transfer of plants and animals is complete.

"We have loaded the coastal zones of the world with massive amounts of plastic and materials that are not biodegradable," lead author James Carlton, a marine sciences professor at Williams College in Massachusetts, says in an interview with the New York Times. "All it takes is something to push this into the ocean for the next invasion of species to happen."

What makes the tsunami debris project unique is that scientists could track — in some cases down to the inch — where the buoys and boats, totes and crates — were coming from and when. Chapman, in fact, has stood in the same spot at Japan's Port of Misawa in the Aomori Prefecture where the dock that changed his life was wrested away.

"This is a major experiment in science and we got to harvest the results," Chapman says. "At no other time in human history was there an experiment so big and we know exactly when these objects were launched."

The Japanese government estimates some 5 million tons of materials washed out in the churning tsunami waves with about 70 percent sinking to the ocean floor, leaving some 1.5 tons that went out to sea.

So far, only a small fraction has been found.

As of October, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program had received nearly 2,000 official debris reports with 72 items confirmed as "definite tsunami debris," according to Jenna Malek, a communication and policy specialist with the program.

"Marine debris is an ongoing problem with everyday impacts, especially around the Pacific, and natural disasters can make the problem worse," she writes in an email to the Journal. "That's part of why it's very difficult to tell where debris comes from without unique identifying information. If a piece of debris is suspected to be from the tsunami, NOAA works with the Japanese government to identify these items if possible."

Malek says the administration worked closely with the study's authors and is "in agreement with the findings presented."

But Chapman cautions that the Japanese tsunami was not the greatest source of marine debris in 2011, not by a long shot, which he describes as "a horrifying thing." And, if those Japanese creatures could make the trek, others can too.

"Now we are connected like we've never been connected before because every shore is connected to every other shore," he says.

What this all means is still hard to say. Invasive species are already a common blight in areas around the globe, but the proliferation of plastic debris making its way into the world's waterways appears to be ratcheting up the pace.

The full impact will likely take years to unfold, Chapman says, noting that the ocean is a difficult habitat to monitor. Whether any of these species can get a foothold on foreign shores will depend on many factors, including whether the climate conditions are compatible.

Regardless, Chapman says, the research comes with two main takeaways: Organisms can make it across the ocean on drifting debris in a way never thought possible and humans are the main factor in allowing that to happen.

"Now," Chapman says, "we are having another kind of human epiphany in how important we are in changing the planet."

Kimberly Wear is the assistant editor and a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 441-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Comments

Showing 1-1 of 1