I blame Serial. Or the holidays. Or 2014's spotlight on our flawed justice system. Whatever the reasons, I was inspired to report for jury duty. I'd never shown up before — too busy and ugh and a million other weak reasons. The process began with 80 of us in the jury assembly room, watching videos about the thrill of serving, the closeness fostered between jurors during trials. "Many jurors stay in touch afterwards," the voice-over intoned. I imagined a sales pitch to introverts or lonely hearts: "Do you wish you could meet people more easily? Make new friends? Try jury duty!"

The videos did not convince the majority of the attendees, apparently, as by the end of the first hour, almost everyone had been dismissed. Based on the visible lack of enthusiasm, I imagined the escapees mentally high-fiving themselves as they slid out the courthouse door into the fresh air of freedom. Barely a dozen of us remained. We returned the following Tuesday to be regrouped with other leftovers into a sizeable pool, and sent upstairs. The stairwell smelled "like reefer," noted one older gent — most of the potential jurors appeared on the upper end of the age spectrum, retirement, perhaps, offering fewer options to dodge the obligation.

The courthouse is drab, all fluorescent lights and no windows. The ladies room, however, is a chipper blue and green. The Honorable Dale A. Reinholtsen was also cheerful as he welcomed us and imparted the specific charges in the case: assault, assault with intent to cause great bodily harm and torture. I flinched at the word "torture." If he'd been describing a movie, I would've said, "No, I don't want to see that." But I was determined to fulfill my obligation as a citizen.

Twelve people were called into the jury box and selection began. The prosecuting attorney, Zachary Curtis, had a boyish face and matter-of-fact manner. The defense attorney, David Lee, was more weathered and theatrical, welcoming each potential juror with enthusiasm and apologies. The questions, asked by the judge, Curtis and Lee, in turn, revealed not only more about the case — in addition to the violence, homelessness and "flashing" were recurring topics — but about the potential jurors themselves. The news that we would have to watch a "disturbing and graphic video" caused a few people to ask to be excused. Others inquired if the torture involved an animal or child and were relieved when told no. "OK, then," they said.

The questioning brought forth things about people that we likely would never otherwise have known: that they had been abused as children, been homeless, been arrested, had a daughter who'd been subject to indecent exposure at work, a granddaughter who'd been kidnapped.

I wasn't sure what to hope for — that they'd have everyone selected before getting to me so I could leave or that I would have a turn in the box. A few people puffed up in the spotlight, answering questions with long stories or sassy remarks — and, really, how do you answer questions like "Do you believe in the law?" with a simple "Yes" or "No," without adding "mostly" or "sometimes?"

I considered what I would say if called. I didn't want to be a puppy, wagging my tail in hopes of being picked. Neither did I consider the moment a platform upon which to place my soapbox. The clerk called my name. I took my seat and answered the questions as briefly, honestly and politely as possible.

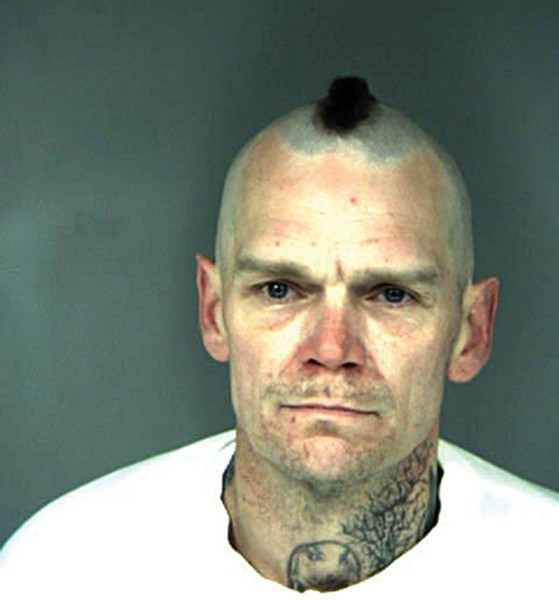

Through all this, the defendant sat at the front of the room, broad-shouldered with a heavy brow and dark, close-cropped hair. A few times Lee pointed at him directly and asked potential jurors if they could judge this man fairly, what with all the neck and knuckle tatts. Fair question. And how strange to be asked to judge our fellow humans when refraining from judging others is such an oft-repeated tenet.

At some point, both attorneys indicated their satisfaction with the jury as it stood.

With that, it was official. I was about to serve.

Day 1: "Madjacking"

Parking around the courthouse was worse than expected. I circled and circled, watching the minutes tick by. Finally I found a spot and raced upstairs — then couldn't remember which courtroom we'd been switched to. An officer in the hallway noticed my distress and sent me to Courtroom 8. I was the last juror to show up. With everyone else already seated, I had that sensation of arriving late to class and expected Judge Reinholtsen to scold me. Thankfully, he just waited for me to sit, then called the court to order.

In films, courtrooms impress. Charismatic lawyers intone with passion, incite anticipation. In reality, the space was smaller than a classroom and the opening statements lacked drama — although we did learn the term, "madjacking" (repeated and vigorous masturbation, for the uninitiated). Both sides agreed on the basics: David Parks, a homeless man, had been badly beaten around the greenbelt area near the Bayshore Mall. At least one person involved had accused Parks of masturbating in the bushes. The defendant, Darin Vitolo, also homeless, was not part of the initial beating, but interacted with Parks later, capturing the encounter in a video — the aforementioned "graphic and disturbing" one — that he then posted to Facebook. When he'd finished making the video, Vitolo transported Parks via cart from the homeless encampment area to the mall parking lot.

Our first witness was Eureka Police Department detective Shawn Sopoaga, broad and tall and otherwise straight from central casting. Curtis had Sopoaga walk us through the initial call.

A naked, beaten man had been found behind Walmart, Sopoaga said, with "I am a perv" scrawled in Sharpie on his back. An initial search of the nearby greenbelt area — the site of dozens of homeless camps — yielded no information.

And then our second witness, the victim, David Parks, limped to the stand. He was maybe my height — 5-foot-6 — and I'd be surprised if he weighed much more than 100 pounds. Lanky brown hair hung to his shoulders. Parks spoke softly in response to Curtis' questions, telling the court that he was living in Old Town, on the streets. He said the beating left him with a brain injury and permanent damage to his ankle. He'd been drinking a beer behind the Walmart, but couldn't recall what happened after. Parks had been in Eureka about four months at this point, he said, but hadn't ever camped in the greenbelt. He remembered waking up in the hospital. "I was scared," he said. "I didn't understand what had happened to me."

During Lee's cross examination, Parks admitted to doing meth the night before the beating. He also said there'd been a "girl" complaining and then other people showed up, all men. He couldn't remember if he'd exposed himself. Yes, he'd been convicted of lewd conduct previously. Parks was excused and shuffled back to his life. We would not see him in the courtroom again.

Day 2: "Crumple zone"

We began with Dr. Thorsen Haugen, a specialist in the human body from, as he put it, from the collarbones up. He had visited Parks in the hospital to consult for possible facial fracture surgery. Parks' head had been swollen "like a pumpkin," Haugen said. At hand, three primary issues: The first, a broken cheekbone, was "mostly cosmetic;" the second, a busted nose; the third and most notable, a situation with the "inferior orbital floor," the bone that holds the eye in place. When that bone is broken, Haugen explained, the injury has greater chance of being life-threatening as the eye may "settle back and down." Imagine how the front end of a car is made to give way in a crash to protect what's inside, Haugen said. Similarly, the face is designed as a "crumple zone" to protect the brain.

Under cross-examination, Haugen elaborated that the bones were broken into numerous small fractures. Could the damage have been from multiple blows? Lee asked. "Either way," Haugen replied. "More likely than not, but I can't say for sure." The damage around the eyes, he conceded, did suggest more than one hit. He again mentioned that the damage to the head included blood in the brain lining and added that Parks had a collapsed lung due to having several broken ribs.

"How does this beating compare to others?" Lee asked.

"It's on the severe end of the spectrum," Haugen answered.

Our next witness, radiologist Timothy Dalsaso, seemed tense and used a lot of medical terminology. He hadn't seen Parks in person, only his X-rays, and listed off Parks' injuries: a complex facial fracture of the right orbital bone, damage to the back left of the brain, skull plate cracked, multiple rib fractures (five on the left and six on the right), which had resulted in displacement, causing respiratory failure, plus the right ankle was fractured.

Given the injuries to the right eye and left side of the brain, the question arose as to whether we were looking at a "contrecoup" injury — one in which an impact on one side causes damage to the opposite. Sure, Dalsaso said, "the brain bounces around a bit." These types of injuries were common in car accidents, but less severe than "if you were to drop this guy off a building." The injuries to the head appeared to be caused by multiple bruises, but Dalsaso couldn't determine the specific cause. He did, however, brush aside the suggestion that the contrecoup injury might have been caused by a left-handed punch to the head. "More likely a kick," he said.

We then took a lengthy break so Curtis could get his next witness, Vitolo's girlfriend, Lisa Pescador. She looked to be in her 40s, wore layered tank tops and unremarkable pants. I wondered if she'd tried to look as nice as possible for court.

Pescador smiled at Vitolo, who smiled back, then wiped a few tears from his eyes. "Do you recognize Darin Vitolo?" Curtis asked. She did. Could she describe him? She did, defining the button-up he was wearing as "a nice shirt." They were engaged, weren't they? Curtis asked. "Yes," she said. As he continued, Pescador's answers came less easily.

She'd been living in the encampment tucked behind the Bayshore Mall when a woman named Tammy — Vitolo's ex-girlfriend — started yelling. Pescador and Vitolo walked over together and saw a naked man, "all bloody," on the main trail, at which point Pescador said she left. "I'm not used to that sort of stuff," she said.

Darin came back to the camp a short time later looking for a Sharpie marker and a phone, she continued. Pescador stayed at the camp and didn't hear anything else. She said Vitolo tried to show her the video at some point, but she didn't want to see it.

Lee's cross-examination fleshed Pescador's story out further. Tammy had told Vitolo and Pescador "the guy was jacking off on the main trail and this was the second time." Tammy kept freaking out, she said. Tammy was drunk. Tammy was being rude because she was drunk. Pescador did not see Vitolo hit the man. She'd been working at an antique store before returning "home ... or whatever ... the campsite." She'd been doing her nails, putting oil on her cuticles, and had needed to keep gloves on. She'd also had to make sure the dogs were tied up. Tammy "is trouble and we don't get along." Pescador had known Tammy was drunk because she was slurring and out of control. "She likes to bully people," Pescador said. "She's always rude, bullying, running her mouth."

Our next witness was Todd Wilcox, a senior detective with EPD for 22 years. Unlike the other witnesses, he aimed his statements at the jury, speaking gently and clearly. Wilcox testified that one of his officers discovered the video during a "routine scan of Facebook." That officer showed the video to Wilcox, who recognized David Parks as the victim and the name of the Facebook user, Darin Vitolo, by reputation. An arrest warrant was obtained and officers "caught up" with Vitolo at the end of Vigo Street, an entrance to the greenbelt area. Vitolo was arrested and later Wilcox returned with a search warrant for his campsite, where he found boots appearing to match the ones in the video. He also found a "spiked leather item" that resembled one on the right ankle "of the person kicking and battering Parks." The confiscated cell phone, which turned out to be Pescador's, had the same video as the Facebook page. When Wilcox followed up with Pescador, she gave him varying statements at different times, but what he ultimately ended up with from her lined up with the testimony we'd heard.

At this point, Curtis brought out the much-anticipated/dreaded video and we settled in. It was brutal, although less gruesome than your average crime flick and, with all the advance warning, easier to watch than I'd expected. Which didn't make it easy at all. Parks is there, naked on the ground, face doubled in size, one eye forced closed by the swelling. Off-camera, Vitolo and, we've been told, Tammy Fontaine, are yelling, telling Parks to state his name "for the record" as they accuse him of being a pervert. We see a boot swing into his head multiple times. At one point, Parks curls to the side and we see "I AM A PERV" written on his back. Parks moans, "It hurts." Vitolo's breathing is heavy. The camera swings back and forth as he tells Parks that this is what happens to "pervs." After a couple minutes, the camera flips around to reveal Vitolo's face. "That's how it's done," he says.

Day 3: 'You've been tagged'

We began the session with Wilcox again at the witness stand, wearing an amazing tie with a galloping horse at the bottom and a giant star at the top. Curtis had us listen to the video's audio file, specifically noting when Vitolo tells Parks, "You've been tagged!" During Lee's cross-examination, Wilcox said Vitolo had confessed to making the video, but stated that Parks was already battered and unclothed. Yes, Parks' description of a woman involved in the initial beating fit Fontaine. No, police had not been able to interview her. "She is a wanted person," Wilcox said.

Day 4: 'I didn't beat his ass'

We listened to a conversation between Pescador and Vitolo recorded during jail visitation. Vitolo tells Pescador not to worry. "I didn't beat his ass ... They don't know I did this," he says.

EPD Sgt. Kay Howden then took the stand. She'd talked with Parks after the beating about what happened to him. "He said he'd been behind the mall drinking a beer," Howden said, "and was told, 'You can't be here,' by someone he didn't know." He had fully intended to comply, Parks had told her. He didn't want to cause trouble and didn't have "a good feeling" about the situation, he'd said. One female in particular had instigated the group assault, but he didn't remember much, just that about four or five men had been involved and that the woman had been mostly egging on the men, but "she got her licks in, too." The rest of his recall was broken up, Howden said. "He didn't know where he was found, no memory of how he got from one place to another."

District Attorney investigator Marvin Kirkpatrick also interviewed Parks several months after the beating. Same story.

Examination, cross-examination, and with that, both sides rested and we recessed until Monday.

Day 5: "... for the purpose of revenge, extortion, persuasion ..."

We began with Judge Reinholtsen instructing us on how to proceed making our decision. He schooled us on the difference between direct evidence (a person walks in and announces, "It is raining") and circumstantial (a person walks in and says, "I saw someone come inside wearing a raincoat covered in drops"). Both carry equal weight. The instructions took a long time. It was mind-numbing. I thought about Virgin America's brilliant safety video and wanted to tell the court there's a better way to deliver this information. I also thought about how strange it was to have the defendant right there, as the judge tells us how we are to decide his fate.

We arrived at the closing arguments, theoretically the most passionate part of the trial narrative ... and Curtis kicked off with a PowerPoint presentation, the gist of which was that we were bound to "the letter of the law." And, for all the tediousness, this would prove true. Curtis played the video again, highlighting how Parks' left eye is swollen shut in the video, but his right eye is not, but in the photos from the hospital, the right eye is much worse than the left — the result of Vitolo kicking Parks in the head, Curtis said, and the cause of the brain hemorrhaging. He pointed out the audible "crunch" indicating a boot coming down on Parks' ankle. Another kick to the head implies true "sadism" and the sign off, "That's how it's done," clearly indicates "satisfaction," Curtis concluded.

Lee's performance contained more flourishes — he brought out the podium as he emphasized how we must only find the defendant guilty "if the People have proved the facts beyond a reasonable doubt" and if these facts prove his client's guilt. But the prosecutor's case fails, Lee said. He called Curtis' interpretation of events an "armchair argument" and asked why more experts weren't consulted. Lee compared the video to that Nathaniel Hawthorne classic, The Scarlet Letter, drawing a parallel between a woman being forced to wear a letter labeling her an adultress and a man being Sharpied and documented via video as a "PERV." A shaming and a warning, Lee said. But, he continued, Vitolo's intent was not to cause injury and, in fact, Vitolo showed restraint — and ultimately took Parks to where he would be found and saved.

Because the prosecution has the burden of proof, it also gets the final word. Curtis again reiterated our obligation to the specifics of the law and said we should take certain statements with a grain of salt. We should rely on what the doctors said — they're the experts. We should believe the video, the audio and the photos, the officers. "You must reject any unreasonable conclusions," Curtis said. As for Vitolo "saving" Parks, Parks would likely have died without medical attention, Curtis said, and a more likely reason for Vitolo moving him is that "it's inconvenient to have a corpse in the bushes." As for the Scarlet Letter analogy? "Sounds like revenge and persuasion to me." He left it to us to come up with a verdict reflecting the truth of what happened.

Day 6: Judgement

I assumed people were burnt out and would be in a hurry to get this over with. I was wrong. The bailiff ushered us into the deliberation room and my fellow jurors settled down to business. Our options were: 1.) to find Vitolo not guilty on any count; 2.) to find him guilty of either assault or assault with force likely to result in great bodily injury — with or without also finding him guilty of torture in regards to the latter. First, we had to choose a foreman. This happened by way of "Well, if no one else wants to ..." until one of the relatively younger guys, a dark-haired, thoughtful-looking gamer type, accepted the job. Then we launched into conversation. People hesitated at first — knowing where to begin didn't come easily — until one juror asserted, "I think he saved [David Parks'] life." The immediate back-and-forth made clear that this was not the popular opinion and grew into a discussion about which interpretation of the video was correct. Some jurors felt Vitolo was just a macho guy defending his territory. "This is a lifestyle we're not familiar with," the more sympathetic reasoning went, and therefore we shouldn't hold the behavior accountable to our own norms.

We all agreed that we weren't familiar with the world in which the crime took place, but the specific question was, did Vitolo's actions do damage to Parks? Or could they have? A construction worker shrugged off the seriousness of a kick to the head, pointing out that on the job site, getting bonked on the noggin' was the usual state of affairs. Another guy disagreed vehemently, relating a time he almost put out a friend's eye during a paintball game, and asserted that any attack on the face was likely to cause significant harm.

We watched the video again. And again. I studied the parts I was supposed to, but I couldn't help but watch the people around me watch it, all of us viewing this grim scene as the woman closest to the player kept jabbing the pause button hoping to catch the moment when the boot swung into the head. Watching a naked, beaten fellow human be further attacked would normally provoke an emotional response, and I believe my fellow jurors must have felt something — disgust, pity, horror, something — but we had to tamp down those reactions to assess clinically.

Unable to quite agree, we referenced the printed instructions, read and re-read the definitions. That the defendant had acted in a manner likely to cause great bodily injury seemed obvious, but when we took an anonymous poll, unanimity was not forthcoming. We asked the question again: Does a kick in the face count? What about when the face in question had already been pulverized? I thought yes. How could anyone say that swinging a foot toward a swollen, bloody, bruised and blackened head was anything other than assault? Hints of frustration took hold as we returned to our definitions. We reasserted that our own subjectivity was secondary to the specifics of the law. By that measure, were the kicks likely to have caused great bodily injury? Yes, we finally agreed. That point squared away, the talk turned to torture. Clearly, Vitolo had been motivated by revenge and persuasion, one factor in the charge. But given the extent of Parks' existing injuries, certainty about what damage Vitolo may have definitively caused was impossible. Therefore, much as some people would have liked to hold him accountable, the law says we must find him not guilty. We were done. We signed the forms the bailiff had given us and buzzed him to return. The waiting lasted five, 10, 15 minutes, during which we began playing a sort of digital charades game called Heads Up that involves holding your phone up to your forehead while people shout out clues. Finally the bailiff showed up and we returned to the courtroom, all levity having evaporated as we took our seats.

Judge Reinholtsen studied our work, then called the attorneys to the bench. Oh, no! We had failed to complete the forms properly. How embarrassing. We were sent back to the jury room for another try. Our foreman took responsibility. We sympathized. It had been confusing, don't worry. The final forms accounted for, we returned to the courtroom.

Verdict, take two. I glanced at Vitolo. He leaned his face into his hands, waiting. The clerk stood up. When she announced that the jury had found Vitolo guilty of assault likely to result in great bodily injury, he shook his head against his palms and then froze again, as if he were holding his breath. I held mine. When she read the "not guilty" of torture, he wept a little. For all the pop culture familiarity of sitting through a trial, the act of determining another person's fate weighed heavily. As it should.

We'd done our best based on the evidence and the wording of the law. Was justice served? To the extent it could be, I suppose. Would the victim benefit in any way? David Parks didn't even remember Vitolo, had come into the situation damaged and been lucky to survive the beating. I saw him walking down E Street a few weeks later, hunched and haunted-looking. The police and other agencies have been cleaning up and clearing out the greenbelt where the crime took place. The city of Eureka is exploring solutions to the problem of people living unpermitted outdoors. Darin Vitolo was sentenced to some time in prison.

If anything positive came out of this case, it was that a bunch of relatively normal people got together in a court of law, heard both sides of a story, examined the evidence and made a call based on the rules our society has agreed should bind us. In this small way, society worked. And I was glad to have been part of it.

Sentencing

By Thadeus GreensonOn March 20, Humboldt County Superior Court Judge Dale Reinholtsen heard two distinctly different interpretations of the facts in the case of Darin Vitolo, who’d been convicted of assault likely to cause great bodily injury about six weeks earlier. The defense argued that Vitolo should receive a grant of probation in the case, describing him as a “Good Samaritan” whose actions ultimately saved the victim’s life. The prosecuting attorney argued that Vitolo is “an amazingly dangerous human being” and a threat to society, warranting a lengthy commitment to state prison. Reinholtsen ultimately sentenced Vitolo to the mid-term of three years in prison, saying he’d inflicted additional injuries on a partially naked man in a defenseless and near comatose state. With 514 days of credit for time served, Vitolo faces about a year and a half of incarceration in state prison but could be out in as little as 11 months.

Comments (7)

Showing 1-7 of 7