News Blog

- Submitted

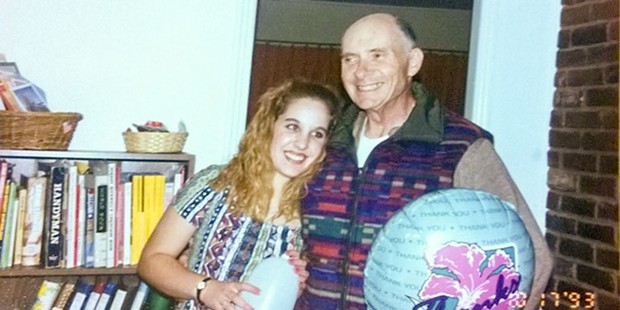

- Amber Slaughter with her grandfather.

According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Dunaway was paroled last month to the San Francisco area. While Dunaway had faced life in prison for the 1994 murder of Amber Slaughter on South Jetty, Francine Schulman told a parole board late last year she’d forgiven Dunaway for her daughter’s killing and wanted to see him released from prison. After extensively questioning Dunaway about the remorse he feels and what he’s done to change his life since entering prison as a teenager for a crime he committed while 17 and legally still a juvenile, the board deliberated for about 20 minutes before recommending he be paroled.

It was the second time the board had recommended Dunaway for parole. The first recommendation, made in 2017, was reversed by then Gov. Jerry Brown, who said Dunaway had remained violent through his early years in prison and didn’t express sufficient remorse for or insight into his actions. Current Gov. Gavin Newsom, however, declined to intervene.

As detailed in a Dec. 27 story in the Journal headlined “I’m a Monster,” Dunaway’s testimony before the parole board in November was extensive, detailing how his troubled youth — he was physically abused by his grandfather and molested by a neighbor when he was 9 — led him to the life of violence and gangs that ultimately led him, Thomas Winger and Abraham Gerving to kill Slaughter, who they felt had been spreading rumors about them. (After reaching a plea deal with prosecutors that saw him testify against Winger and Dunaway, Gerving was paroled about halfway through a 16-year prison sentence. Winger died while serving a 25-to-life sentence in state prison.) During the hearing, retired Humboldt County Assistant District Attorney Wes Keat called the killing “brutal,” “senseless,” “atrocious” and “planned.” But the board’s task at the hearing wasn’t to re-litigate the murder, it was to determine if Dunaway still posed a danger to society.

Parole Board Commissioner Michele Minor asked Dunaway directly how he could assure the board and the governor that he has taken responsibility for his actions, that he understands them and would be leaving prison markedly different than when he was admitted 21 years ago.

“I didn't know how to change who I was," he said. "I thought I was stuck being that person. I thought that that's all I was destined to ever be was this scumbag white trash from a scumbag poor white trash family, and that was my identity, and since then I've developed an identity. I understand who I am. I understand that — that things I do such as ... being a 12-step counselor and mentor to other inmates, these things allow me to gain the self-worth I lacked all my life. They allow me a true sense of accomplishment and they make me feel good about myself and it shapes a good, positive, healthy identity that I never had as a kid, that I didn't have until I was 30-something years old. And I look back and I'm ashamed that it took me that long to develop it. I'm ashamed that it took me all those years to really understand how I impacted the Slaughter family, what I did to Amber, what I did to her sisters, her mother and her father, her grandparents, her cousins, what I did to their community, and I'm aware of what I did because I hear the words they say and their voice. I hear the words they say to describe what I did to them. I listen. I understand. I'm the monster."

Schulman, meanwhile, is working toward her masters in social work at Humboldt State University and forming Broken Spirits Rising, a grief support group for those who have suffered the murder of a loved one.

Asked about Amber in an interview with the Journal late last year, Schulman said the eldest of her three daughters loved animals and raised pigs, ducks, geese, sheep and rabbits in 4-H. She often helped Schulman with her landscaping business and was good to her younger sisters, who were three and five years her junior.

“She was like a fluttering butterfly,” Schulman said, smiling.

Comments