Mother Nature is just not on Last Chance Grade's side.

Caught between an eroding coastline and three massive landslides on unrelenting marches toward the ocean, the long-failing highway section with an ominous name doesn't seem to stand a chance.

Battered by deluges of rain in recent months, the already geologically-challenged portion of U.S. Highway 101 just south of Crescent City lost another 10 feet in a March slipout. The mountain, quite simply, is moving and the recent spate of wet weather is only speeding it up.

Just drive onto Last Chance Grade and the signs are immediately evident: The cracked, uneven pavement runs through roadway basins — one section dropped 5 feet in the last year — and a main retaining wall with sagging segments reveals gaps at the base.

Caltrans, meanwhile, continues to patch, repair and reinforce the desolate stretch of road that connects California's northernmost reaches to the rest of the state, constantly working to keep pace with a 3-mile-long target that has shifted 50 feet west since 1937.

"It's neverending," says Sebastian Cohen, a major damage engineer for Caltrans who has managed the Last Chance Grade project for the last three years.

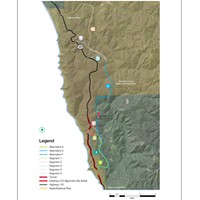

Just along the 22 miles of highway that separate Klamath and Crescent City, some 200 active and historic landslides have been mapped in recent years.

"As the mountain moves up and down, our road moves up and down, and the ocean is just eating it away," Cohen says.

That movement has accelerated in recent years, renewing calls to once again find a way around the unstable terrain that, so far, has only had one full closure — for a four-hour stretch — in recent memory.

A major failure could cut businesses in Humboldt and Del Norte off from their suppliers and clients, children from their schools and sever a vital link between Del Norte County's southern residents and their seat of government.

"It's like a flea on a donkey," Cohen says of the roadway. "You can strap that flea down to the donkey but it's just going along for the ride. The donkey is the one making the decisions."

The same geological forces that created some of California's most spectacularly rugged coastlines are also wreaking havoc on Last Chance Grade.

Called the Franciscan Complex, the land formation is basically a mishmash of rock haphazardly thrown together by the immense tectonic energy exerted when one plate slips under another.

Geologist Ken Aalto, a professor emeritus at Humboldt State University who has mapped the western coastline from Cape Blanco in Oregon to Punta Gorda to the south, described the process like "a great mixer."

"It's all mixed up and sheared up," he says.

Last Chance Grade sits in what is known as a "broken formation" comprised mainly of fragmented shale, siltstone and thick bedded sandstone that form the soaring cliffs being undermined by the ocean. When toes of the slopes reach a vertical mass, gravity takes over, causing slipouts like the one last month.

Meanwhile, the deep-seated Wilson Creek, North Last Chance Grade and South Last Chance Grade landslides are each slowly making a descent toward the ocean at different rates — almost as if the earthen masses aren't getting along. The Last Chance slides alone span a combined 2,200 feet and all three traverse the mountainside above and below the road.

Throw in some heavy rains and things can really get moving.

"On the whole, from an engineering perspective, that section of coastline is pretty stable but nevertheless it does fail ... and you can't stop those, so you're left with the question: What do you want to do?" Aalto says.

"All I can say is there is a severe problem and it's not going to get better on its own," he adds.

While Aalto is quick to point out that he's not a registered geologist, he says his lifetime experience studying the Franciscan Complex — the formation of which only became understood in the late 1950s and '60s with the emergence of plate tectonics theory — leaves him concerned about the roadway's future.

"No one can predict when a major failure will occur on that slope but we know it will," Aalto says.

But nothing about the Last Chance Grade project is simple.

Landslides have been the road's constant companion since the original wagon trail was built in 1894 — one was called Last Chance Slide, which stuck. Construction on the current alignment began in 1933 but faced constant delays due to area's trademark instability. Even then there were proposals to move the highway inland but they were ultimately derailed by cost.

Now the situation boils down to two main choices: Continue with the constant and costly maintenance — a tally of more than $54 million since 1981 — needed to keep the road open with fingers crossed there won't be a massive landslide or build one of six proposed routes to sidestep the problem area.

For folks like Blake Alexandre, there's a lot on the line. His family's business, Alexandre EcoDairy Family Farms, relies on U.S. Highway 101 to bring in regular hauls of hay and grain and to ship eggs and milk out to markets south of the ranch, which sits nestled along the Smith River in Del Norte County.

With his organic farm necessitating about 50 trips along the stretch each week, any closure would mean a grueling 320-mile, seven-hour reroute via U.S. Highway 199 to Interstate 5 to State Route 299 — costing time and money.

There's no doubt the stakes of a closure are high: Caltrans found Del Norte County alone would lose $300 million to $400 million per year in economic output with some 3,000 to 4,000 jobs on the line.

Alexandre says anyone who drives Last Chance Grade on a regular basis can literally watch new twists and turns develop over short periods of time — including a noticeable drop in the roadway that took place in February.

"There's multiple challenges along the road and some are maybe more urgent than others," he says.

During recent trips to Washington, D.C., Alexandre met with his representative, Jared Huffman, as well as congressmen Peter DeFazio of Oregon and Doug LaMalfa, who represents Northeastern California, to discuss the highway's predicament.

He says the officials understand a workaround is needed, if not necessarily the urgency of getting the project moving.

"When you can tell it changes from week to week, that's a different concept than, 'It's been failing for years,'" Alexandre says.

For his part, Huffman says that he along with other state and federal officials are committed to preventing the "mother of all road closures" at Last Chance Grade and he is cautiously optimistic the project is gaining momentum with its many pieces beginning to fall into place.

"I think people need to understand we've been working at this very intensely for the last couple of years, and I wish that I could just snap my fingers and have all the approvals and funding necessary to relocate Last Chance Grade, but it's complicated and it does take some time," he says.

While the consensus is the road needs to be relocated, an overwhelming array of hurdles stand in the way. Even if funding the multi-million to billion-dollar project wasn't enough of a challenge, each of the proposed alternatives presents major obstacles.

There are old growth redwoods, park land and private property, endangered species, areas of cultural significance to local tribes, challenging geology, untouched wilderness and even a United Nations' World Heritage site to contend with.

Just about everything that could raise a red flag on a major construction project is on the table.

Staying put has its own complications, including the eventual need to cut into the cliffs up the ridgeline to widen the roadway, bringing down old growth redwoods in the process.

Before an alternative route can even be selected from the list of contenders with varying levels of cost and complexity, environmental and geotechnical studies are needed on each one — with a five-year timeline for completion and an estimated price tag of $50 million.

"Everything about the project is unique and challenging," Cohen says. "That's what it should be called, Unique and Challenging Grade instead of Last Chance Grade."

Until recently, none of those studies could even get started. Guidelines for the needed federal emergency relief funds precluded Caltrans from getting a jump on the analyses because that would flag the project as addressing "preexisting conditions" rather than a disaster event, making it ineligible for the funds.

That changed a few weeks ago, when the Federal Highway Administration informed Caltrans that any advanced studies would no longer be held against the project — with the caveat that funding still is not guaranteed.

Huffman calls the news "a positive sign."

"I'm keenly aware, after a season of landslides and road closures, just what it means to these communities and we want to do all we can to protect against what would be the mother of all road closures along the Last Chance Grade," he says.

With $5 million allotted, the initial drilling tests can begin.

"The geotechnical studies are really going to drive home where it's feasible to do what," Cohen says.

The six proposed routes range from a 1-mile-long tunnel — which Cohen described as "extremely expensive" and "extremely challenging" — to nearly 12 miles of new road, including a pass through the Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Forest.

None, Cohen says, stand out as an obvious choice with preliminary cost estimates running from $300 million to $1 billion. The shortest and cheapest route, for example, goes right through virgin redwood forest.

Longer routes designed to avoid the ancient trees have corresponding consequences: tremendous building costs and cumulative impacts to wildlife and the environment.

"Chances are it's going to fall in the middle somewhere," Cohen says.

At this juncture what's most important is getting everyone on the same page, says Huffman, who formed a stakeholders group that includes environmental groups, landholders, tribal officials and concerned community members.

"We are much more likely to move this thing forward proactively than if everyone is all over the map fighting with each other," Huffman says.

Meanwhile, he says, the stakeholder group has forged a general agreement that a realignment is needed — even though that means making choices one would want to avoid in a perfect world.

That still leaves the issue of funding.

Gone are the days, Huffman says, when individual members of Congress could author legislation to pay for a particular project, which means the best hope for Last Chance Grade is federal emergency relief monies. The immense cost of the project rules out conventional state transportation resources.

"What has to happen is we've got to qualify for an existing program that funds projects like this," Huffman says. "We've got to compete ... and we've got to convince federal highway officials that this is where they should put those dollars."

Huffman says he and other local officials, including state Sen. Mike McGuire, who has worked extensively on the project, have their eyes out for other openings.

But, he doesn't hold much hope for a major federal infrastructure bill coming to the rescue.

"I'll be looking at every opportunity along the way and if something faster and better comes along, we'll jump on it," Huffman says.

DeFazio, a ranking member on the House Transportation Committee who toured Last Chance Grade in the fall, has also said he supports the move. With only $100 million a year allocated for emergency relief funds, projects across the nation depend on bills coming out of the powerful committee to increase the pool.

One aspect working in favor of Last Chance Grade is that the wide assortment of governmental agencies that will eventually need to sign off on any selected route are taking the unprecedented position of participating in the planning to head off potential issues, rather than waiting for the studies to be completed.

That, Cohen says, is a "game changer" that will streamline construction "down the line."

But the cumbersome process is frustrating for those who depend on Last Chance Grade and believe it's a matter of when — not if — the road will give way.

Those include Crescent City resident Kurt Stremberg, whose parents were killed when their car went off a collapsed section of the roadway during a storm in 1972.

It was still dark as the couple returned home in the early morning hours after dropping Stremberg, then a recent college graduate, at this friend's home in nearby Klamath.

Stremberg says not more than 15 minutes could have passed between their trip south and the time of the accident.

"In the time I drove Last Chance and said goodbye to them and they turned back, the road was gone," he says.

The Realtor says he stayed away from the issue for years before joining a push in 2011 to bring the highway back to the collective forefront.

That year was a major turning point in the current resolve to find a solution after the roadway's sudden accelerated movements drew renewed attention from Caltrans, federal transportation officials and residents alike.

Stremberg was a high school student in 1964 when the dual disasters of a tsunami and the flood struck Crescent City in the same year. He says the region took generations to recover — a scenario he fears will repeat itself if Last Chance Grade experiences a monumental failure.

"That's the kind of thing I hate to think about that we might be facing," he says, adding that he hopes people in Del Norte, Humboldt and even Curry counties recognize the stakes.

Stremberg, who sits on the stakeholders group set up by Huffman, prefers the shortest route, saying it will ultimately result in fewer impacts.

In the interim, he'd like to see some sort of warning system, like electronic signs posted at each side of the grade. More and more, Stremberg says, he hears from people afraid to make the short drive over the failing section of highway.

"We can sit here for 20 years waiting for a bypass to be built but we ought to know what the condition of that road is in real time," he says.

Right now, the Last Chance Grade project is stuck in a waiting game. First, the Federal Highway Administration needs to determine the road is unworkable at its current location.

Once that hurdle is overcome, the next step is procuring federal emergency relief funds to pay for the remainder of the studies and, ultimately, the project's construction costs.

That would require a waiver to build the roadway outside of its original perimeters, which is not without local precedent — that's how the Confusion Hill bridge was funded.

Cohen says his main job is keeping Last Chance Grade open and safe to travel.

Caltrans crews walk the grade each day to track every crack and crevice and, every six months, Cohen goes up in a U.S. Coast Guard plane to observe conditions from the air. During inclement weather, crews stay on site 24-hours a day to observe any developments.

When human feet aren't on the ground, gizmos and gadgets ranging from load sensors to GPS units monitor the earth's movements in near real time.

By the time the 10-foot section slipped last month, Cohen says Caltrans had been prepared for the eventuality for more than a week.

Regardless, there's still a long road ahead. The current timeline has an estimated completion date of 2039.

"This is a legacy project," he says, noting such massive undertakings take decades.

The problem, some say, is the road — and the communities that depend on it — may not have that much time.

Kimberly Wear is the assistant editor and a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 441-1400, extension 323, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @kimberly_wear.

Comments (7)

Showing 1-7 of 7