It was an unusual request for the drab, staid confines of Eureka City Council Chambers.

"Do I have time to sing you a song?" she asked from the podium.

"Sure," then Mayor Frank Jager replied.

With that, Cheryl Seidner, a Wiyot tribal elder, clad in a traditional knit cap, tilted her head back, eyes closed, and began to sing. As the words of "We're Coming Home" sung in Wiyot began to fill the room, slowly, one by one, the crowd rose to its feet. City staff followed suit, then members of the city council, until the entire room stood in rapt attention. When the song came to a close, Councilmember Kim Bergel turned away, dabbing tears from her eyes.

The moment underscored the gravity of the action the council took a few minutes later, when it voted unanimously to declare more than 200 acres of city-owned land on Indian Island "surplus property" and directed the city manager to negotiate its return to the Wiyot Tribe, for whom the island was home for at least 1,000 years, according to an archeologist, and since time immemorial, according to the tribe. But in Wiyot culture the island represents more than an ancient village site or a historical homeland — it's the physical and cultural center of the universe, a place with the spiritual power to bring balance to all else.

Tribal Chair Ted Hernandez underscored this when he addressed the council that evening, saying he refused to call the island — named Duluwat in the Wiyot language and encompassing the villages of Tuluwat and Etpidohl — "surplus property" as it was bureaucratically being dubbed.

"It's sacred land," he said. "This is our sacred property. It's where our ancestors are. That's where our ancestors are buried, and that's what we recognize it as. It's the center of our world."

Following the council's direction given at that Dec. 4, 2018, meeting, City Manager Greg Sparks and the Wiyot Tribe are currently working to finish the paperwork needed to officially transfer ownership of the land back to the tribe. It's a move without precedent across the nation, according to numerous experts consulted for this story, all of whom said that while there have been instances of the federal government, nonprofits and private entities returning land to tribes, Eureka appears to be the first local municipality to have ever taken such a step.

- North Coast Journal/Jonathan Webster

- The Wiyot Tribe's acquisition of Indian Island

The largest of three islands in Humboldt Bay, Indian Island, comprised mainly of tidelands, is about 280 acres in size, stretching nearly a mile long and a half-mile wide. Up until the mid-1800s, the island was home to two Wiyot villages with Tuluwat serving as the site of the tribe's annual World Renewal Ceremony, which drew members from throughout the region, where as many as 3,000 Wiyots lived in approximately 20 village sites scattered around Humboldt Bay.

A shell mound on the north-east end of the island was carbon dated back to the year 900 A.D. by a University of California Berkeley professor in 1918, indicating Wiyot inhabitance of the island went back at least a millennium.

But when whites were drawn to Humboldt County in the mid-1800s, they brought disease and violence that devastated the Wiyot people. By 1852, only about 800 Wiyot people remained in their traditional homeland, according to a 1993 article by Debra Webster for the Humboldt County Historical Society.

Like other tribes, the Wiyot Tribe was decimated by institutionalized violence, human trafficking and systemic genocide at the hands of their new white neighbors. The most famous of these atrocities occurred on Indian Island 159 years ago next month.

The Wiyot Tribe was in the midst of its World Renewal Ceremony in late February of 1860 when groups of white militiamen conducted three simultaneous raids on sleeping Wiyot villages on the south jetty, at the mouth of the Eel River and at Tuluwat, combining to kill as many 300 Wiyots before the sun rose.

Nowhere was the carnage fiercer than Tuluwat. The Wiyot men were away from the village gathering supplies for the renewal ceremony as the village's women, children and elders slept, when a still unidentified group of white men massacred them. Journalist Bret Harte documented the aftermath in grim, graphic detail for the Northern Californian newspaper:

"When the facts were generally known, it appeared that of the some 60 or 70 killed on the island, at least 50 or 60 were women and children," he wrote. "Neither age nor sex had been spared. Little children and old women were mercilessly stabbed and their skulls crushed with axes. When the bodies were landed at Union, a more shocking and revolting spectacle never was exhibited to the eyes of a Christian and civilized people. Old women, wrinkled and decrepit, lay weltering in blood, their brains dashed out and dabbled with their long gray hair. Infants scarce a span long, with their faces cloven with hatchets and their bodies ghastly with wounds. We gathered from the survivors that four or five white men attacked the ranches at about 4 o'clock in the morning. No resistance was made, it is said, to the butchers who did the work, but as they ran or huddled together for protection like sheep, they were struck down with hatchets."

In the aftermath of the massacre, the Humboldt Times opined that it should be blamed "on the troops of Fort Humboldt because they had not given complete protection to the settlers and the settlers were left no course except to take matters in their own hands." (Read more about the massacre in the Journal's Feb. 25, 2010, story "Genocide and Extortion.")

Survivors of the massacre sought "immediate asylum" at Fort Humboldt, according to Webster's article, but were soon relocated to Fort Terwer on the Klamath Reservation and then dispersed throughout the region.

By the time of the massacre, work was already underway to seize ownership of the island from the Wiyot people. In 1858, John T. Moore submitted a claim with the Federal Land Claims Office under the Swamp and Overflow Lands Act to take ownership of the island and received a "certificate of purchase" for the property in January of 1860, which he sold to Robert Gunther the following month, according to Webster's article.

With the Wiyot people killed or removed, the island would then endure more than a century of abuse. It was diked to drain the saltmarshes to create land for cattle grazing. A series of lumber mills left a toxic legacy, as did a dry dock boat-repair shop that operated on the island for 120 years. In the early 1900s, the island was home to the Sequoia Yachting and Boating Club, where Eureka's wealthy and elite would boat across the bay for days of swimming and picnicking and rollicking evening balls.

A fire destroyed the club in 1913, and another gutted Gunther's historic Victorian home on the island some decades later. The city of Eureka purchased ownership of about 250 acres of the island in the 1950s from Ida Bohn Gates, who'd sued Gunther's estate for the island in 1909. For decades, the island lay largely fallow, save for four private residences on its Eureka-facing side and an egret rookery on the opposite side. Over time, the egrets took on a mythic quality, becoming a symbol of the island's brutal legacy.

"The egrets, in graceful flight are the spirits of those who were massacred so long ago," reads an unattributed quote in a 1988 Humboldt Historian article by Virginia Sparks. "Loathe to give up their island, they hover near, keeping vigil while the island fulfills its time of mourning."

- File photo

- Indian Island, looking toward the Tuluwat village site in 2004.

In the first months of 2014, running unopposed for his second term as Eureka's mayor, Jager found himself doing a lot of reading. He was researching his grandfather, a member of the Pottawatomi, a Great Plains tribe that fought alongside the French in the French and Indian War in the 1700s. In the aftermath of the war, the tribe was removed from its historic homelands and relocated to Oklahoma and Kansas.

That got Jager thinking about the removal of the Wiyot from Tuluwat, and Humboldt County's own legacy of genocide and theft. As mayor of Eureka and the grandfather of two Wiyot girls, he thought he could offer a simple gesture to heal old wounds, so he spent a weekend in mid-March drafting a letter to the tribe.

"In February 1860, 154 years ago, citizens from Eureka participated in what has been described as a massacre of unfathomable proportions," the letter began, going on to describe the attack on "that winter night long ago" when women and children were slaughtered. "As Mayor of Eureka, and on behalf of the city council and the people of Eureka, we would like to offer a formal apology to the Wiyot people for the actions of our people in 1860. Nothing we say or do can make up for what occurred on that night of infamy. It will forever be a scar on our history. We can, however, with our present and future actions of support for the Wiyot work to remove the prejudice and bigotry that still exist in our society today."

The letter was released to the public before it underwent legal review by then City Attorney Cyndy Day-Wilson, which posed a problem. While many in the public found the letter a heartfelt and long-overdue apology to take responsibility and make amends for a more than century-and-a-half-old massacre, Day-Wilson saw a financial liability. While legal experts widely agreed that was nonsense — that apologizing for a crime carried out by unknown people 14 years before Eureka was officially incorporated would in no way expose the city to liability — the council followed Day-Wilson's advice and edited the letter, removing mention of who attacked the Wiyot that day or anyone being sorry for it.

Jager's letter had been gutted.

"Of all the things that happened when I was the mayor, that was probably the most disappointing," he said, adding that some weeks later he traveled south to the Wiyot Tribe's Table Bluff Reservation to address the tribal council and apologize to them as a private citizen.

Recollections of that meeting differ. Jager says he recalls apologizing and telling the council about how he hoped to see the city erect a monument on the island commemorating the massacre. But Hernandez, the Wiyot Tribal chair, says he recalls it differently.

"He apologized and said, 'What else can we do?'" Hernandez says. "We said, 'Return the island.'"

What's clear is that Jager's gesture with the letter opened the door for something more, pushing both the tribe and the city to rethink what was possible.

"For him to come to the tribe and to apologize, I thought that was courageous," Seidner says. "I was happy that evening."

A few months later, Natalie Arroyo and Kim Bergel won seats on the Eureka City Council. One of the first things Arroyo did after being sworn in later that year was to travel to Table Bluff to address the Wiyot Tribe. Arroyo says she'd worked closely with the tribe in her capacity at the Redwood Community Action Agency on some grant funding efforts to build a smokehouse on tribal land. Once elected, she wanted to see if was anything the city could do to build a better government-to-government relationship with the tribe.

"They said, 'Well, please give us back Indian Island,'" Arroyo recalls with a chuckle, adding that at the time she didn't even realize the island was within the city's jurisdiction, much less under the city's ownership.

Seidner, meanwhile, had already been in Bergel's ear on the subject. Unbeknownst to anyone, the return of Indian Island was quickly becoming a reality.

- File photo

- Indian Island, looking toward the Tuluwat village site in 2004.

Sitting in the cultural office of the Wiyot Tribe's headquarters on Table Bluff, Seidner says she's been working to see Indian Island returned to the Wiyots her entire life. She knew it would happen, she says, but didn't think she'd live to see it.

Growing up, Seidner says she first learned of the island and the massacre from her mother — "her people were from the bay," she says — when she was about 5. Immediately, Seidner says, she started picturing the island's return.

"When I was 10 years old in fourth grade, Mrs. Greg asked who discovered America," she recalls. "Some little boy said, 'Christopher Columbus.' I stuck my arm up and said, 'No. The Wiyot people were already here.'"

Seidner tells the story, in part, to emphasize the fact that the Wiyot people have never left. "We're here," she says. "We aren't shadows today. We are not forgotten."

Nor have they forgotten the island, or its importance as the physical and cultural center of their universe. The fact is, Seidner says, the Wiyot have been working toward this day for a very long time. She talks about her uncle Albert James suggesting in 1970 that the tribe push for the return of the island, of the tribe's lawsuit against the federal government in the 1980s that resulted in it gaining its tribal status.

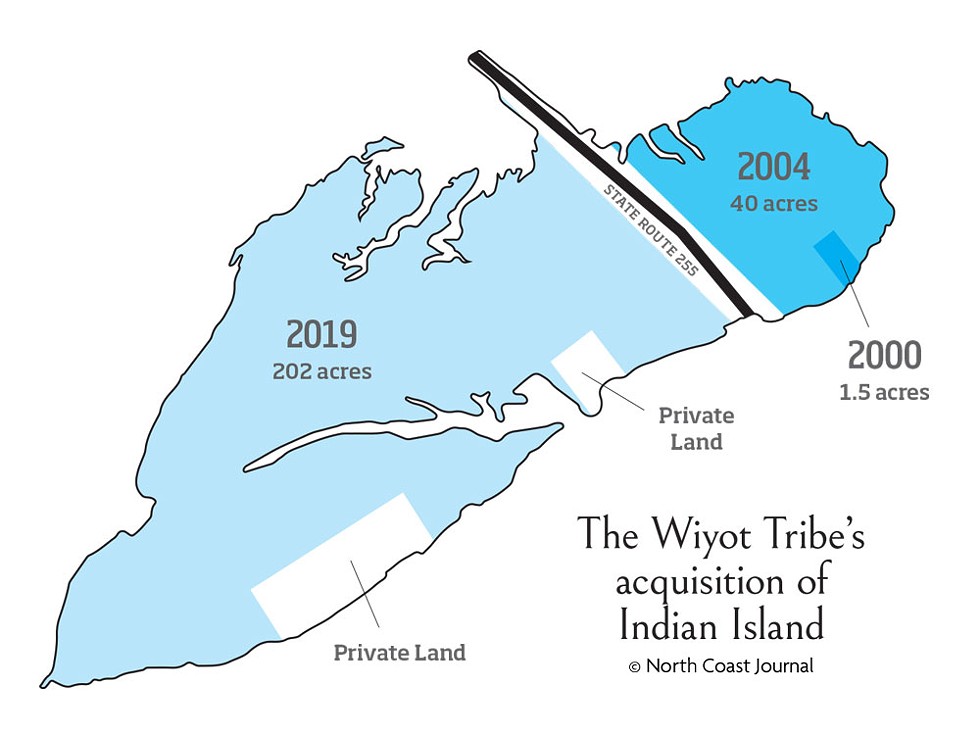

In 1996, after she was elected to the tribal council and became chair, Seidner herself put getting the island back at the forefront of the tribe's agenda. When the city put 1.5 acres of the island, a parcel that included Tuluwat, up for sale for $100,000 in the 1990s, Seidner pushed to make the purchase a priority.

She recalls one day in 1998 when she was on the Humboldt State University campus selling fundraising posters for $10 apiece and asked a professor to buy one. The next day, he returned in a suit and tie and asked Seidner to sit down. He'd talked to his wife, he said, and they agreed to match any donations up to $40,000 toward the purchase of the sacred village site.

A handful of months later, Seidner says she was speaking about the efforts to purchase Tuluwat during a conference of the National Congress of American Indians. When she finished addressing the crowd, a man stood up with a $100 bill in his hand and urged the few hundred people in attendance to match. Seidner says she raised almost $40,000 that day.

The tribe went on to hold auctions and events, and sold T-shirts, baked goods and Indian tacos. After missing a purchase deadline by a couple of days, it sold more until it reached the now $106,000 needed to purchase the 1.5 acres, signing the transfer deed in 2000. A handful of years later, the city donated an additional 40 acres to the tribe, which secured a variety of grants to clean up toxic contamination from lumber mills and a shipyard. In 2014, tribal members gathered on Tuluwat to finish the World Renewal Ceremony that had been interrupted by the massacre, the first step toward bringing balance back to the universe.

"My great uncle Irving James used to be a lightweight boxer," Seidner says. "He used to say, 'Every time I got knocked down, I got back up.' I look at the tribe and we're the same way. We've been knocked down a lot of times in our history but we always get up."

- File photo

- Aerial view of Indian Island.

In the weeks since that December meeting when the Eureka City Council formalized its intent to return the island and directed the city manager to get it done, Hernandez says he's gotten a steady stream of phone calls and emails from other tribes or tribal organizations with a single question: "How'd you guys do it?" Arroyo says she's received similar inquiries from the National League of Cities and other municipalities.

It's clear Eureka and the Wiyot Tribe are on the cusp of something special.

Bob Anderson, the director of the Native American Law center at the University of Washington School of Law who for six years served under Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, providing legal advice on issues of Indian law and sovereignty, says what's being done is simply without precedent. While there are many examples of the federal government returning stolen lands — like giving 48,000 acres back to the Taos Pueblo Indians — or of a private entity, nonprofit or land trust acting similarly, he's not aware of a single instance of a local municipality returning land to a local tribe absent a lawsuit.

"I think it's a big deal," he says. "It sets an important precedent for other communities that might be thinking about doing this. They can say, 'Yes, it's been done before in California.' It really sets a positive tone for relations between tribes and local governments, which have very often been very strained.

"This is a significant example of sort of forward-looking, modern good relationships between tribal government and non-tribal governments," Anderson continues. "It seems to me this could be a shining example of what's possible. It's very important to Indian Country."

While everyone involved in the transfer seems wary of celebrating too early — Seidner says she "won't be ecstatic until people's names are written on the documents" — it's also clear they view this as the beginning rather than the culmination. Hernandez and Seidner say the tribe is already fundraising, looking to raise $15,000 to hold a World Renewal Ceremony on the island in 2020. Tim Nelson, the tribe's natural resources director, is already working on plans to rid the island of invasive Spartina grass. Jager's successor Susan Seaman says she's bringing a proposal forward at the city's next council meeting aimed at formalizing a "more collaborative" relationship with the Wiyot Tribe that will give it "a stronger voice at the table" in the city.

Careful to note that the return of the island is the fruit of generations of Wiyot work, Hernandez says the tribe is just focused on taking care of the island, "bringing it back to health." Asked if the tribe is entertaining the idea of trying to get back the private property on the island, too, to own it in its entirety, Hernandez chuckles and shakes his head.

"That's individuals' homes," he says. "We know what it's like to be taken off our land. Why would we do that to someone else?"

Asked what it will feel like to set foot on the island once it is returned to the tribe, Hernandez takes a deep breath.

"I imagine what it will be like and I just get this sensational feeling," he says. "Ancestors — you can feel their presence there. It's an amazing feeling. You don't want to leave. You're just absorbing it and feeling the power it has."

In the words of that unattributed myth in the Humboldt Historian, the island's period of mourning is almost over. The Wiyot are returning home.

Read the Journal's 2004 coverage of the Return to Indian Island.

Thadeus Greenson is the Journal's news editor. Reach him at 442-1400, extension 321, or [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @thadeusgreenson.

Comments (8)

Showing 1-8 of 8